This article is an on-site version of our The State of Britain newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every week. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good afternoon, on what may, in hindsight, be viewed as an important week in Sir Keir Starmer’s proposed makeover of Britain: on Monday the government finally published a green paper outlining plans for its industrial strategy.

I say ‘may’ because publishing papers and holding consultations (yes, there is another consultation on industrial strategy) are no guarantee there will be change. Indeed, the stack of such papers gathering dust in Whitehall suggests that, more likely than not, it won’t.

The ‘Green Paper’ consultation was, I’m told, downgraded from a ‘White Paper’ setting out legislative proposals, which isn’t a great sign in itself, but as Giles Wilkes argues for the Institute for Government here, it’s not a bad document.

It identifies eight high-productivity sectors the government wants to focus on including life sciences, business services, creative industries and advanced manufacturing — so, no surprises there — but also promises “temporary catalytic government support to scale up industries”.

That implies the government will actively look to pick some narrower, subsector targets to drive innovation — something that, post-Brexit, the previous government talked a great deal about, but largely failed to deliver upon.

Will Labour be different? We must hope so, because as Martin Wolf sets with typical clarity here, in a world where the government can’t rely on investment to generate growth it must look to planning reform, regulatory reform and the “promotion of innovation” — with the last of these “particularly important, given the dire performance on productivity”.

The CEO of pharma giant Eli Lilly, David Ricks, made the same point ahead of Starmer’s investment summit on Monday, telling Radio 4 that if the UK is not going back into Europe (which we’re not, per Starmer red lines) then the UK has to sharpen its offer to the world.

“The difference in the UK is that you’re on your own now, and it’s a relatively small market, so something needs to be quite different to make it interesting — so flexibility, agility and business responsiveness. That’s a path we’d encourage,” he said.

Can we do this? In theory, we can, but candidly the record since Brexit doesn’t inspire confidence — and worryingly, it’s been poor despite the previous government being emotionally and rhetorically committed to delivering the kind of environment Ricks described.

Three years after the ‘Benefits of Brexit’ report was published, we are still waiting, for example, for legal changes that would improve processes at the Food Standards Agency (FSA), such as removing the need for unnecessary reauthorisations and requiring statutory instruments to bring regulated products to market.

And as Linus Pardoe, UK policy manager at the Good Food Institute Europe, points out, the FSA still hasn’t provided detailed proposals on how it will modernise its regulated product authorisation process, such as accepting risk-assessments from other trusted regulators to speed things up.

I’ve written before about the capacity constraints of the FSA in delivering a competitive service for novel food technology businesses, a clear example of an under-resourced regulator failing to compete with those in the US or Singapore.

Big ambitions

That, in theory, is why Labour has launched its new Regulatory Innovation Office, for which I interviewed the science minister Peter Kyle earlier this month. He has big ambitions for the RIO, but offered scant detail on its powers, chair, budget and staffing levels.

Kyle chose to launch the RIO at the Translation & Innovation Hub at Imperial College London — a beacon of British ingenuity — where one young founder of a food biotech firm told him directly how “companies have failed” because regulators take too long to grant approvals.

The minister announced £1.6mn for a ‘regulatory sandbox’ for the FSA — which was welcomed by Pardoe and industry figures — but is in no way a game-changing investment when you consider the agency has faced effective cuts of £30mn-£40mn as a result of budget freezes imposed by the previous government.

Applications to the US Food and Drug Administration are dealt with by a designated contact-person, while applications to the UK’s FSA disappear into a bureaucratic black hole, according to Cai Linton, co-founder and chief executive of Multus Biotechnology.

As Linton explained to Kyle, investors and founders need clear responses and timelines from regulators. “Funding might give you two years of runway, but if responses are taking two to four years, then companies fail. You need to know how you’re progressing.”

So while it’s great to have a sandbox to examine how things could be done more efficiently, the fundamental issue according to founders, investors and policy experts I’ve interviewed say it is really about capacity.

And as Pardoe observes, on this the jury is still very much out.

“With major legislative changes to the regulated product system still uncertain and the FSA’s budget tightly constrained, it remains to be seen if the UK can establish a future competitive advantage in regulating alternative proteins.”

Picking targets

Kyle knows all of this, but in a world where Whitehall budgets are massively constrained and bureaucratic inertia is a feature of the system (see above) it is very far from clear that, despite his best intentions for the RIO, it will actually make a difference.

It could — as this briefing by the UK Day One project explains — but not without money, fierce political concentration and, most importantly of all, a determination to pick some individual sectors in which to make a difference.

The author, Andrew Bennett at Form Ventures, an early-stage VC fund investing in the future of regulated markets, reckons that it won’t work without a £100mn budget, an external chair and real commitment from No 10 and the Treasury.

The stultifying combination of what Bennett summarises in ‘three Rs” — a lack of Resources, failure to update Rules and a lack of Risk appetite — holds back industries from pharma to nuclear, novel food to fintech. Bennett, who is an alumnus of the Tony Blair institute, writes in the briefing:

“It is critical that the RIO is not just the next iteration in a long line of failed regulatory reform initiatives, but leads to a genuine step-change in pace, urgency and delivery to fulfil its intended potential.”

We have been here before but in a more halfhearted sort of way. The medical regulator, the MHRA got £10mn to clear the clinical trials backlog; there’s a £10mn fund for AI regulatory capability and a £12mn Regulator Pioneers Fund all of which, as Bennett observes, is “too subscale to touch the sides of the problem”.

Because if, as the Health Secretary Wes Streeting admitted this week, “lower growth [from Brexit] is a fact of life we have to deal with”, then the UK needs to have a really urgent debate about its “offer” to the world and how it makes itself attractive to the likes of Eli Lilly.

New bodies like the Regulatory Innovation Office and the Industrial Strategy Council must not turn into talking shops, but — as Peter Mandelson set out in a speech in Edinburgh last week — drive difficult choices and concentrate resources.

“[The Industrial Strategy Council] should . . . provide the intellectual support ministers need to make unpalatable choices, notably in investment over consumption trade-offs and choices on research funding for key foundational science and technologies.”

That’s the difference between an aspiration and a strategy. And it’s one that needs to be implemented with ruthless focus and honesty about the UK’s post-Brexit predicament which — to date — has been conspicuously lacking from both main parties.

Join FT experts on November 1 at 13:00 UK time to discuss the UK’s economic prospects in the light of the new Labour government’s first Budget. Register for your exclusive subscriber pass here and put your questions to our panel now. And before you go why not try our new Budget game where you get to be the chancellor Rachel Reeves.

Join FT experts on November 1 at 13:00 UK time to discuss the UK’s economic prospects in the light of the new Labour government’s first Budget. Register for your exclusive subscriber pass here and put your questions to our panel now. And before you go why not try our new Budget game where you get to be the chancellor Rachel Reeves.

Britain in numbers

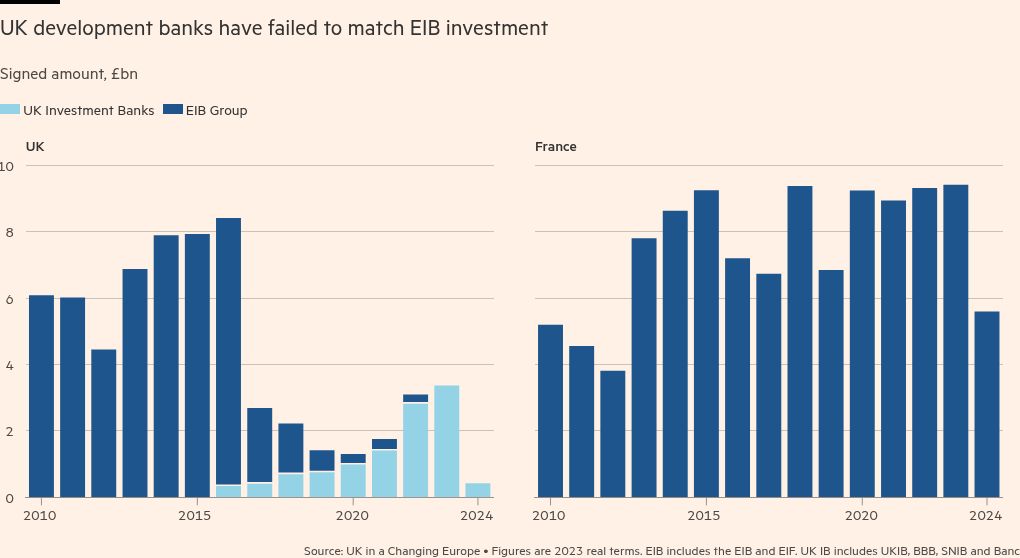

This week’s chart comes from a startling piece of analysis by Stephen Hunsaker at the UK in a Changing Europe, which finds that the UK has “potentially lost £44 billion” in investment as a result of the UK’s ejection from the European Investment Bank (EIB) after Brexit.

That’s obviously a significant sum, given the current emphasis from the chancellor about the need for investment and the UK’s long-standing underperformance in public investment relative to OECD competitor countries.

(It also puts an arresting number on the counterfactual cost of Brexit, the ‘what might have been’ which never really lands in the political conversation.)

What Hunsaker is observing is the gap between what the UK would have received from the EIB if we’d remained in the EU (based an extrapolation from what France has received since 2016) and the level of investment generated by the range of domestic development banks, like the UK Infrastructure Bank (UKIB), that the UK now relies upon.

Hunsaker finds an improvement in the “volume and variety” of funding from the UKIB and others since his original report into UK post-Brexit development banks published last year, but says the investment shortfall “remains substantial” and is “likely to persist for years”.

In numerical terms, from 2010-16 the UK received an annual average of £6.8bn in financing from the EIB, in real terms — almost the same as the £6.6bn France averaged over the same period.

But post-Brexit (2017-2023) UK projects received an annual average of £2.3bn in financing from its replacement investment banks, barely a quarter of the £8.6bn that France received in financing from the EIB over the same period.

“It is not a stretch to say that had the UK stayed in the EU it would have received similar levels of EIB financing. On this assumption, UK annual public investment could have, potentially, been 73% higher had the UK not left the EU. In real terms, that amounts to a potential loss of over £44 billion since 2017.”

Hunsaker warns there is “no quick fix” to the UK’s investment predicament. He estimates the UK replacement banks are at least four years from closing the gap with the EIB, although when you look at the EIB investment gap with France, you can see the gap is likely to be much higher.

As he concludes: “This presents a significant challenge for the new Labour government and its plan for growth.”

The State of Britain is edited by Gordon Smith. Premium subscribers can sign up here to have it delivered straight to their inbox every Thursday afternoon. Or you can take out a Premium subscription here. Read earlier editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Your essential guide to money, interest rates, inflation and what central banks are thinking. Sign up here

Swamp Notes— Expert insight on the intersection of money and power in US politics. Sign up here