Unlock the US Election Countdown newsletter for free

The stories that matter on money and politics in the race for the White House

The writer is executive chair of the Sutton Trust, a social mobility charity

If the American dream promises ascent on merit to those who work hard, then surely access to a good high school education sits at the very heart of it. And yet, when you delve into the data on the US schools system you find underachievement at alarming levels. The latest OECD rankings found that US school students are doing worse in maths than whole swaths of the developed world.

Why, despite being one of the highest spenders on education globally, is the US falling short? One of the underlying reasons came home to me a while ago in New York. A friend — an old Etonian — surprised me by saying he was sending his son to the local high school. “The school funding in the district where we live is better than most private schools,” he explained. He didn’t need to tell me that it was way in excess of much poorer areas such as, say, the Bronx, just a few miles away.

This patently unjust set up is, at least in part, the direct consequence of school district funding, wherein schools are financed through local taxation. On the surface, this may seem a reasonable approach, with local communities supporting their own schools. But in reality it’s deeply flawed, tying the financial health of a school district to the prosperity of its community. It creates dramatic gaps between low- and high-income areas, magnifies existing inequalities and perpetuates a cycle of disadvantage — children in poorer places are deprived of the educational opportunities given to those in wealthier areas. My old friend wasn’t a fool.

Richer districts, buoyed by high property values and an affluent tax base, can allocate substantial resources to schools. This translates to smaller class sizes, better facilities and access to more and richer cultural experiences. In contrast, poorer areas struggle to generate money, leading to fewer well-qualified teachers and less up to date learning materials or extracurricular activities.

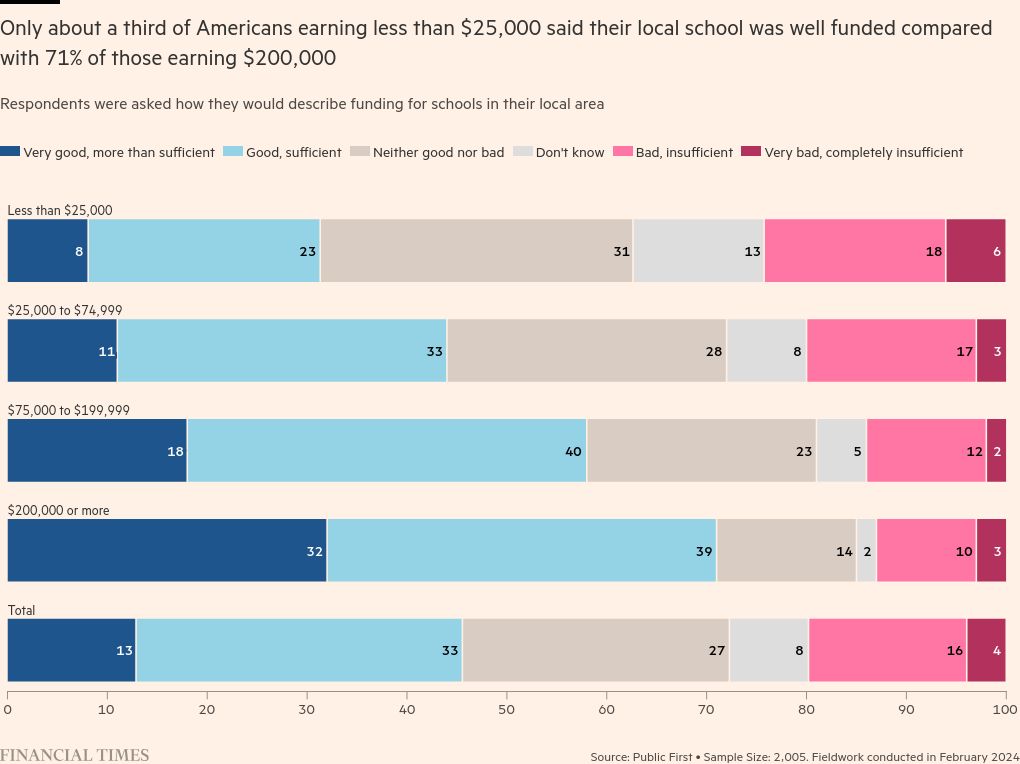

I commissioned polling firm Public First to find out how US voters feel about these funding disparities. Only 31 per cent of the poorest Americans are happy with how their local schools are funded compared to 71 per cent of the richest. Parents understand that the impact of these differences is not limited to the academic performance of students. It has long-term consequences that hinder their ability to break free from the cycle of poverty.

This disparity chokes off social mobility. And growing disillusionment with the undelivered promise of material improvement feeds into a tussle over the very foundations of US society.

This crisis of confidence will only be resolved when the American school system is radically redesigned. Several potential solutions could deliver a more equitable system.

First, implementing state-level funding models that prioritise equality could help bridge the gap between affluent and poorer districts. There is state funding, but by no means enough. By decoupling school funding from local property taxes, states could ensure even resources.

Second, ensuring that all students have high-quality educators is paramount. Implementing programmes that attract and retain skilled teachers in low-income districts, either through financial incentives or professional development, could have a significant impact. Of course, as it stands, higher salaries are impossible for many of the poorest districts.

An election year is the opportunity for bold new thinking. US friends are often surprised when I tell them that in the UK the poorest students are funded better than their more affluent peers. Both Kamala Harris and her running mate Tim Walz have a long record campaigning for progressive education reform. So there is hope.

The US social contract is predicated on the American dream being tangible and achievable. Right now, regressive school funding ensures that the dream remains, for far too many, just that.