Oscar Darko-Sarfo sounds enthusiastic about his new job as a barber — a huge break for a 22-year-old who once doubted he would find work. He was born with a cleft palate, which impairs his ability to speak clearly; it’s not always easy for listeners to understand him.

Darko-Sarfo is one of 20 Ghanaians testing out artificial intelligence-enabled technology developed by Google to help people with non-standard speech. After speaking in English into a smartphone trained to recognise his speech patterns, a female, American-accented voice announces: “I’m working as a barber. I like to do Afros.”

The app, still in prototype, has improved Darko-Sarfo’s ability to communicate, he says — and with it his confidence. In addition to acquiring a job, he has recently found a girlfriend.

Google’s automatic voice recognition technology, called Project Relate, is a tiny example of how AI can help tackle problems in what researchers refer to as “low-resource settings”.

AI is being marshalled in multiple fields on the African continent, which contains some of the poorest countries in the world: in Zambia, to help improve medical diagnostics; in Kenya, to enable farmers to identify crop disease; and in Ethiopia, to tailor education materials to pupils’ needs.

In the 18 months since AI became front-page news, there has been extensive discussion of how it will change society: its effect on jobs, on elections, on science, even what it means for the future of humanity. That conversation has centred largely on the rich countries where it has been developed.

Darko-Sarfo’s case illustrates many of the possibilities this new technology offers for Africa and in developing nations more generally, but also the pitfalls. On one hand, an AI-powered device has helped him overcome his speech issues in a country with limited health resources and just a handful of speech therapists. On the other, Google’s technology is not yet available in his first language, Twi Asante. There is no guarantee it will be widely adopted.

Gifty Ayoka, a Ghanaian speech therapist, whose NGO Talking Tipps is testing the technology in conjunction with University College London’s Global Disability Innovation Hub, is cautiously optimistic about the role AI can play in her country and others like it. “If we can truly embrace this, it will make things easier for people,” she says.

But she also worries that Ghana’s state and society will not be able to properly absorb a technology developed abroad. “Without awareness and training, plus local language and cultural support, no application — however clever — is going to be useful,” she says.

Proponents argue that AI can help poorer societies “leapfrog” whole phases of development in the same way that many countries, lacking landline infrastructure, enthusiastically adopted mobile phones in the early 2000s. Once handsets spread, new innovations followed, allowing people to use their devices for everything from financial transactions to paying for access to solar power.

“Well-run digital systems make states more capable,” said Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates in an interview with the Financial Times last year, in which he extolled the virtues of developing nations embracing the digital revolution.

To optimists, AI presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to go one step further. Machine learning, they argue, can turbocharge the leapfrogging phenomenon by putting revolutionary tools into the hands of individuals, businesses and states.

“I believe in the transformational effect of tech,” says Yordanos Asmare, an Ethiopian who is head of talent at A2SV (Africa to Silicon Valley), a US-based impact incubator that seeks to develop African AI capabilities.

But many, including Asmare, worry AI could have precisely the opposite impact, amplifying the advantages of richer nations that have more computational power and computer engineers, and leaving other countries trailing.

Bright Simons, co-founder of Imani Centre for Policy and Education, an Accra-based think-tank, says Africans produce less than 0.5 per cent of machine learning and large-language models. “We’re already starting out at a much lower base compared to the rest of the world,” he says. “The AI leapfrogging theory completely dissolves, because in AI you’re already marginalised.”

James Manyika, Google’s senior vice-president for technology and society, who grew up in Zimbabwe, says that the risks of falling behind make it all the more important for the continent to forge ahead. “AI presents an opportunity too significant to ignore for Africa,” he says.

In May, Microsoft president Brad Smith gave a speech in Nairobi to mark a $1bn investment in Kenya. In combination with G42, an Abu Dhabi AI company, Microsoft is building what it calls a “comprehensive package of digital investments” including a geothermal-powered data centre and an innovation lab.

AI, Smith told his audience, was a technology comparable to the printing press and electricity. And while Africa partly missed out on previous transformative technologies — 142 years after Thomas Edison’s invention, 43 per cent of Africans still lack access to electricity — the same need not happen with AI, he argued. “One needs to bring three things together: human capital, financial capital and technological innovation.”

FT Edit

This article was featured in FT Edit, a daily selection of eight stories, hand-picked by editors to inform, inspire and delight. Explore FT Edit here ➼

While the challenges of creating an AI “technology stack” — data centres, AI models and developers — were considerable, he said, they were achievable. And AI played to the strengths of a continent where the median age is 19, the youngest in the world.

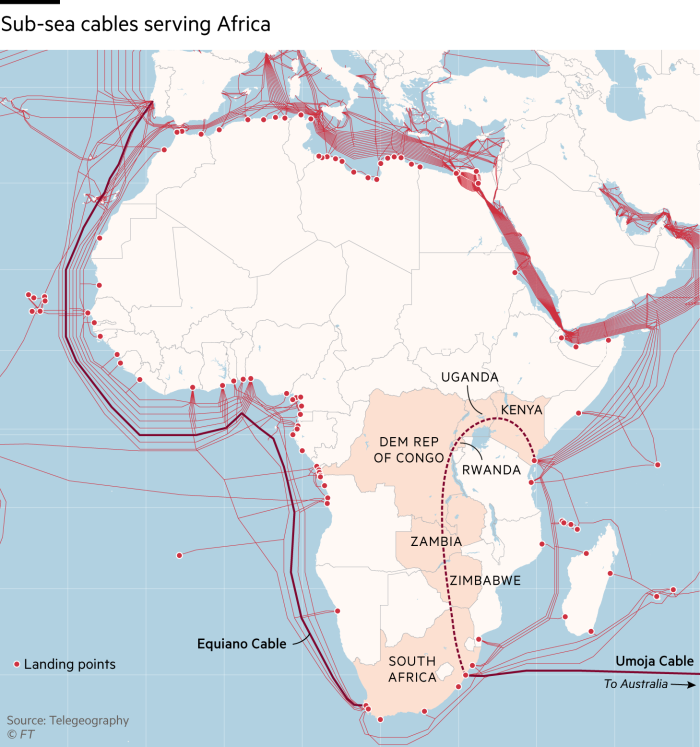

Google has also made an AI push in the region, opening an AI research centre in Kenya in 2022 to add to the one it built across in Ghana in 2018, which was the first of its kind in Africa. Seeking a business opportunity, access to talent and a chance to influence how a continent that will have 2.5bn people by 2050 engages with the technology, it has also committed to spend $1bn on digital infrastructure. Investments include a cable linking several east and central African countries to Australia and another from Portugal to South Africa.

At Google’s AI research centre in Accra, where Jason Hickey leads a team of software engineers recruited from across Africa, the mood is upbeat. “This is a transformative technology,” says Hickey. On the sixth floor of a rented office building, Google software engineers are working on AI-powered tools to, among other things, predict famines and map buildings, including informal settlements that can be invisible to satellites.

MohamedElfatih MohamedKhair, a software engineer from Ethiopia, explains how Google is building an AI model to monitor flash floods in real time. Parts of Africa have a paucity of weather radars; to address the problem, Google has designed a model that combines data from two types of satellites.

“We use AI to fill in the gaps. That’s our hack,” says Hickey. Far from being a bargain-basement version of better-resourced systems, he says, the AI model beats standard methods. “Yes, we want to do it on the cheap. But we’re actually able to get better forecasts from AI.”

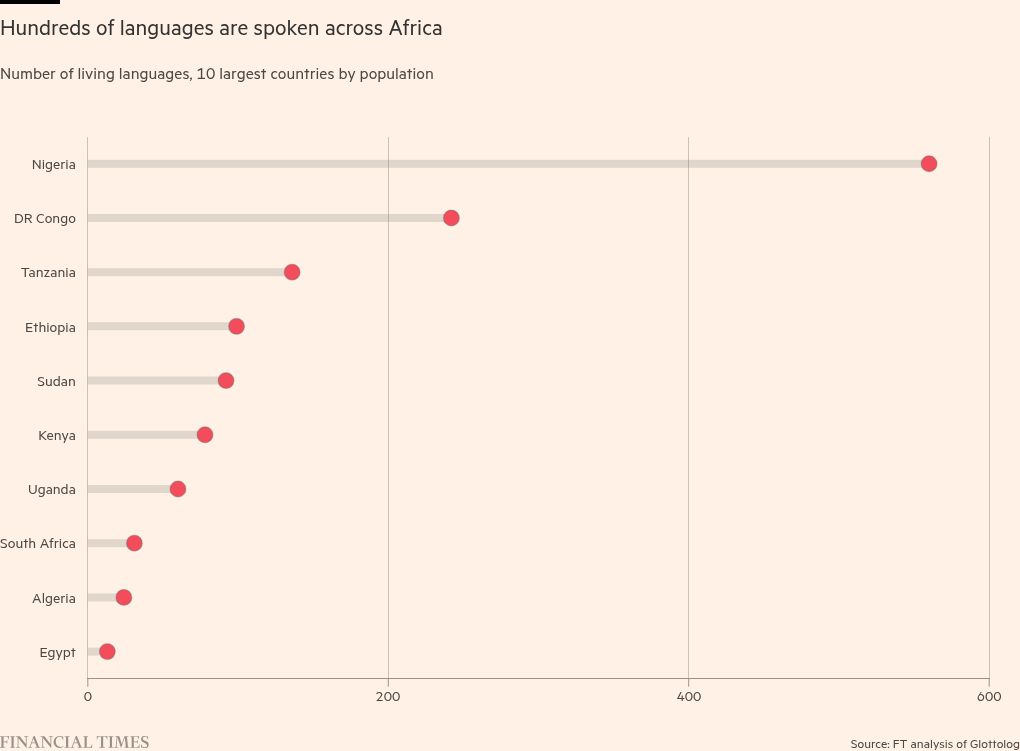

One area where experts see big potential benefits is education, both through interactive learning and, more broadly, by teaching in relevant languages. There are at least 1,000 languages in Africa, yet, thanks to the legacy of colonial history and the languages in which educational materials are produced, many students learn in their second or third tongue, putting them at a huge disadvantage.

“In Africa, people speak their language at home but learn everything in English or French. All their images and books are western,” says Simons, the Ghanaian think-tanker. “So how do we use natural language processing to generate more local content, to create textbooks in local languages and to record oral history?”

A2SV, the impact incubator, has developed an AI-powered “personalised learning” tutoring programme called SkillBridge, which uses Amharic and Afan Oromo, the two most widely spoken languages in Ethiopia, to coach pupils taking the country’s university entrance exam. Of nearly 675,000 students who sat the test this year, only 5.4 per cent passed.

“It raises a lot of questions around the quality of education, but also about what are you going to do with all these young people and about the productivity of the country,” says A2SV’s Asmare. The hope is that SkillBridge can improve results.

Healthcare is another area with potential, argue AI enthusiasts. In many countries, ultrasound equipment is too expensive and trained sonographers are in short supply. Ninety-five per cent of pregnant women in Africa have no access to scanning, according to Angelica Willis, a Google AI researcher.

The company has developed an AI model to analyse data collected from cheaper portable ultrasound equipment deployed by novice operators. A study in Zambia found that AI could assess gestational age and foetal malpresentation from “blind sweep ultrasounds” to the same standard as trained sonographers using standard equipment. If it were adopted more widely, this could save many lives.

While AI promises much, some fear that the technology — like many before it — could not only reflect existing global inequalities, but exacerbate them. “We call it technology amplification theory,” says Catherine Holloway, a professor of interaction design and innovation at UCL.

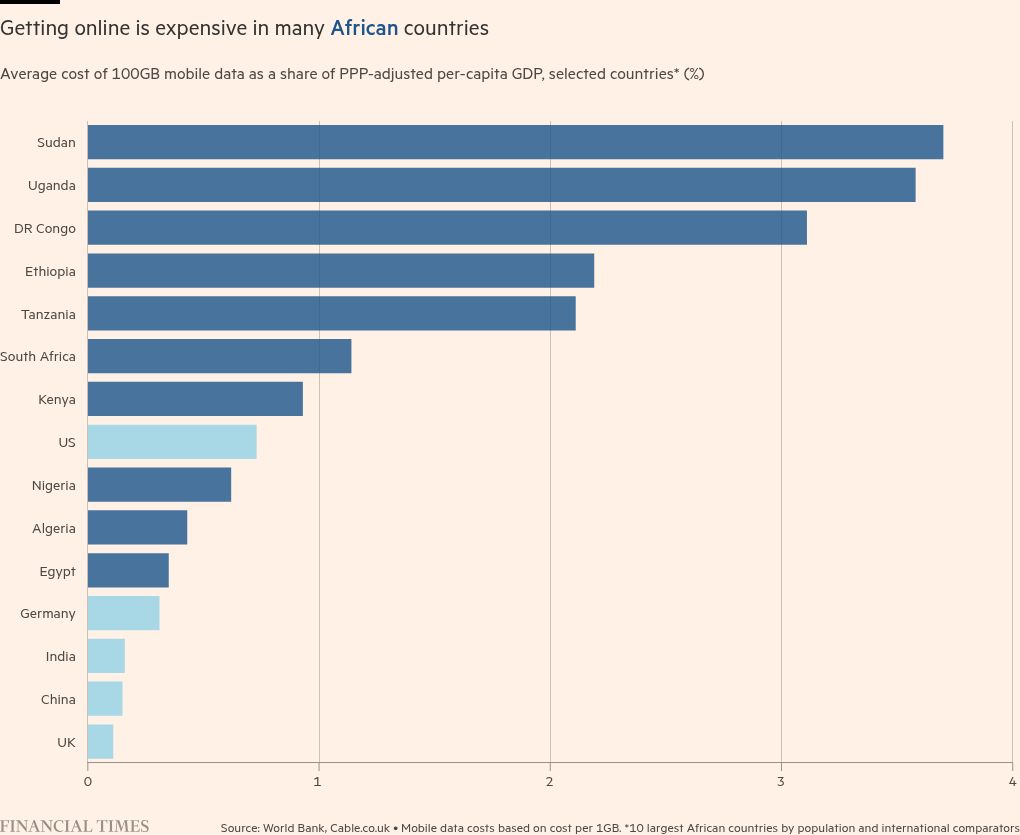

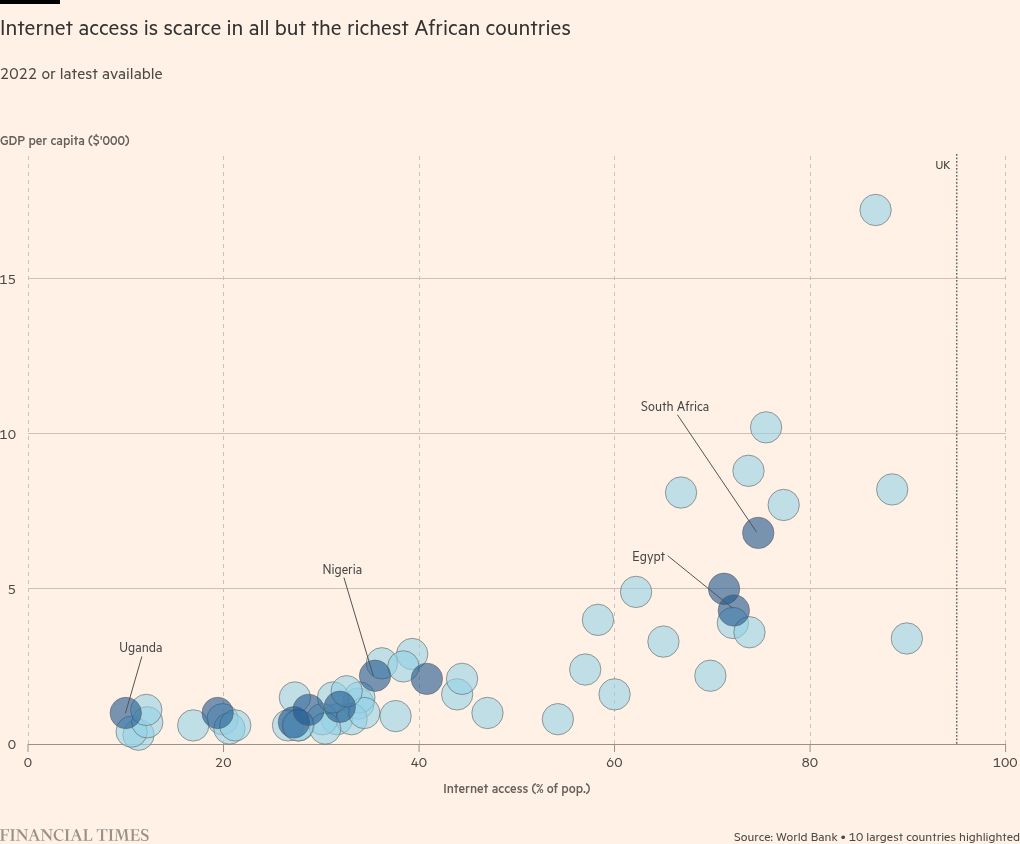

Google’s Manyika, who is also co-chair of the UN’s high-level advisory body on AI, acknowledges the danger of what he calls an “AI divide”. “AI is computer-intensive and we know that device and data costs [in Africa] are the highest on Earth,” he says.

Simons argues there are limits to tech’s ability to patch up dysfunctional governance systems. “For 80 per cent of problems, AI will be the cherry on the top,” he says. But in countries that lack a functioning health system, decent roads and power, or a reasonably accountable state, there are few shortcuts, he says. “Nobody needs cherries if they don’t already have the cake.”

Simons also points to familiar anxieties — the threat to data privacy and ownership and the risk that AI could be exploited by bad actors, including states. In 2020, Ghana, even though it has a thriving democracy, purchased 10,000 security cameras from China as part of a face-recognition system. However creatively civil society uses AI, Simons says, “tyranny [could be made] much easier”.

Some campaigners are also concerned about a potential “data grab” in which a few big, almost exclusively US, corporations are collecting data from Africa and building tools that they can sell elsewhere. Campaigners have pointed to what they say is the exploitation of African labour in data centres, where people working for as little as $2 an hour are training AI models for big tech companies.

“It could be Ghanaians feeding ChatGPT, for example, and that data is in the US,” says Asmare, who joined A2SV after moving from Ethiopia to study at Stanford and work in Silicon Valley, and who now lives in the US. “Where does that data go? Are governments thinking about that?”

There is also the issue of Africa’s astonishingly rich variety of languages. Until now, most large language models have been built using English databases, with all the built-in inequalities that implies. Some African languages are primarily oral with little digital text, such as Wikipedia entries, to feed into natural learning processing models.

SEE Africa, a Tanzanian NGO, has designed a voice-enabled interactive app to help rural women navigate the commercial opportunities of growing a highly nutritious type of sweet potato. It needed its app to work in Swahili. Yet although the language is spoken by some 200mn people across east Africa, there aren’t sufficient data sets for AI models to work on, says EM Lewis-Jong, director of Common Voice, an open-source resource funded by the Mozilla Foundation, a non-profit group working to keeping the internet accessible.

“The Anglo-centrism of the internet is a sort of colonialism in another form,” she says. “Heritage, culture, the particular features of your existence, are so deeply intertwined with language,” she says. Even something as apparently universal as the thumbs-up sign fails to cross linguistic boundaries: in several African languages, it can be an insult.

So Common Voice is harnessing AI to tackle the issue. Individuals or organisations such as SEE Africa can upload up to 1,000 hours of speech in their own language (or combination of languages) on to its platform, either reading out sentences or obtaining copyright-free material from local radio stations and the like to coach natural language models.

“Speech technology has huge potential to be impactful in low-literacy communities,” Lewis-Jong says. “AI could genuinely make language a bridge and not a barrier.”

Equiano Institute, a South African AI think-tank, has ambitions to build an African-owned and operated large language model. “Just as ChatGPT provides an LLM model, we want to provide that solution in Africa,” says Daniel Akinmade Emejulu, who chairs Equiano’s advisory board.

Google, too, is building large data sets in several African languages from its Ghana research centre. “Earlier this year, we added another 110 languages, of which about a third were African,” says Google’s Manyika.

Despite the challenges, Manyika says he remains convinced that AI offers a unique chance for poorer countries to “level up” by flattening access for individuals and businesses to tools and knowledge, and by providing states with the means to tackle big societal challenges.

“I fundamentally believe that AI represents an opportunity not only for the world,” he says, “but for developing regions like Africa in particular.”

Big companies such as Google, Microsoft and Amazon, which says it is investing $1.7bn to expand cloud and AI services in Africa, will continue to invest in the continent — albeit with what are, by their standards, relatively modest amounts.

What impact AI has, however, says Simons of Imani Centre, will never be a purely technological problem, but a question of how it is absorbed by states. Technology, he says, can only improve people’s lives if it can cross the “interface” between cyber space and real-life, from what he calls “the world of bits to the world of atoms”.

Hickey cites the example of countries deploying Google’s AI weather forecasts. “Ultimately, we can provide the information. The final step of engagement with farmers or people who are affected by floods needs to be done through effective engagement with the community,” he says.

If governments in rich countries are struggling to grapple with the consequences of AI, still less legislate for it, in developing societies the situation is even more challenging. Simons says that unless states are using AI themselves, they cannot hope to understand or regulate it.

Ayoka, the banker turned speech therapist, is frustrated at what she sees as a lack of ambition from Ghana’s government despite its digital-first rhetoric. “All this tech is so advanced, but our government is sleeping.”

Many African governments talk a good game about being open to AI, agrees Asmare at A2SV, but she would like to see more strategic thinking. “My question is, do you have the safety guardrails to make sure your people are not exploited, and that these investments are in line with what the country and the people need?”

Google’s Manyika argues that Africans are best-placed to steer use of the technology in their countries. “What Africa does with AI should be Africa-led,” he says.

Cartography by Steven Bernard and data visualisation by Clara Murray