This article is an on-site version of our Chris Giles on Central Banks newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Tuesday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Take a look at the economic evidence. Economic activity far better than expected. Core inflation edging higher. A government with a loose grip on its public finances. This is America.

The large American economy I am describing, however, is Brazil, where interest rates stopped falling in September and the central bank raised them from 10.5 per cent to 10.75 per cent on September 18.

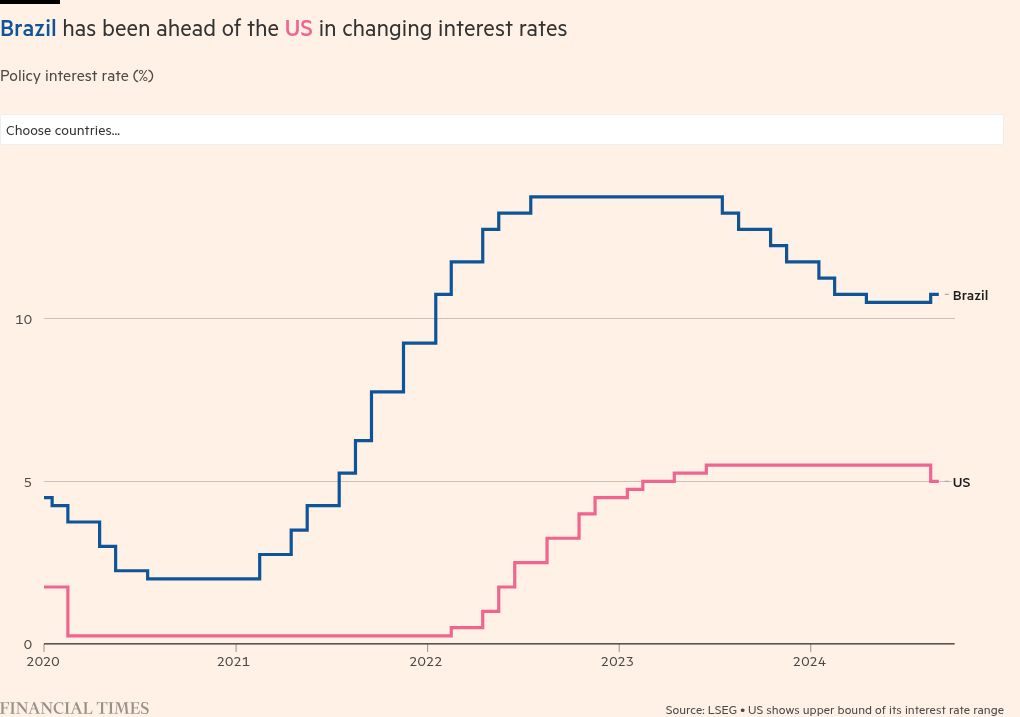

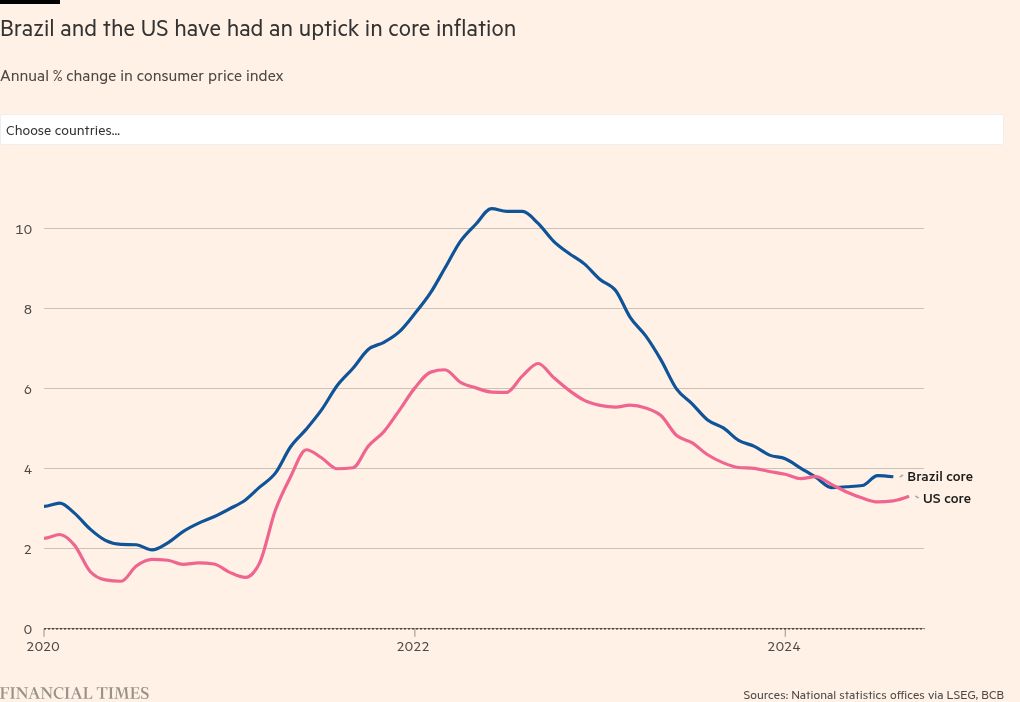

In the past few years, Brazil has been something of a canary in the coal mine for the US, highlighting risks and trends in monetary policy about a year in advance and its central bank has arguably been less behind the curve than the Federal Reserve. The question is whether Brazil is again pointing to future inflationary problems in the US after its central bank started to raise interest rates in September.

When it increased rates by a quarter point last month, the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) noted stronger than expected economic activity, persistently above target inflation, rising inflation expectations and financial market perceptions that the government was a bit lax with its budget. How much has the US to learn from the recent turning point in Brazil’s interest rate cycle?

Similarities

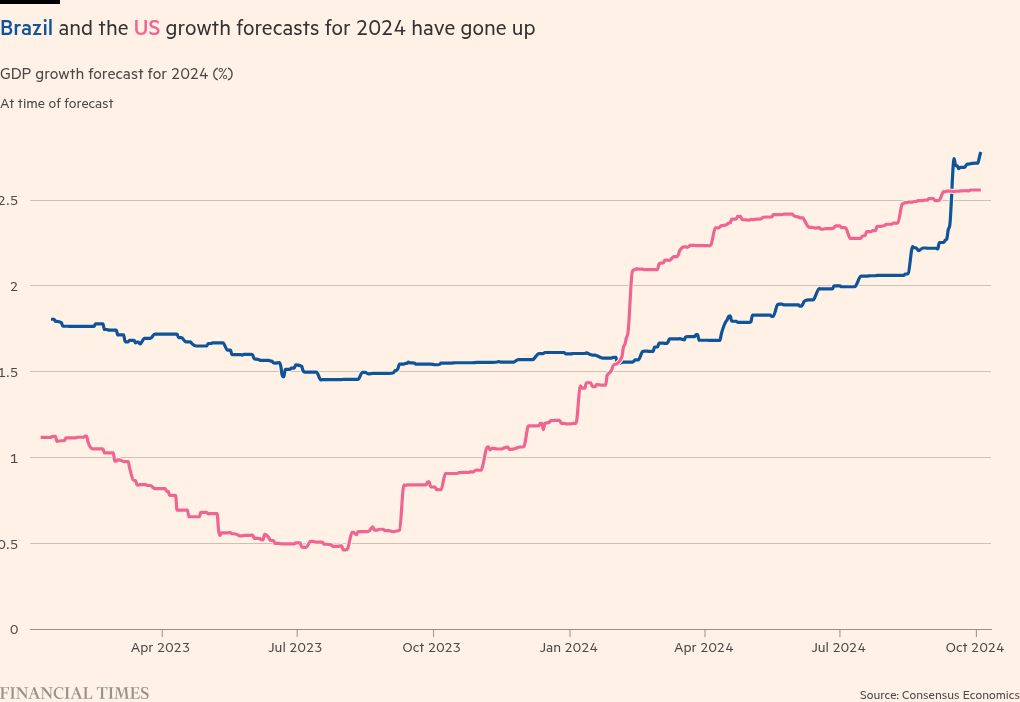

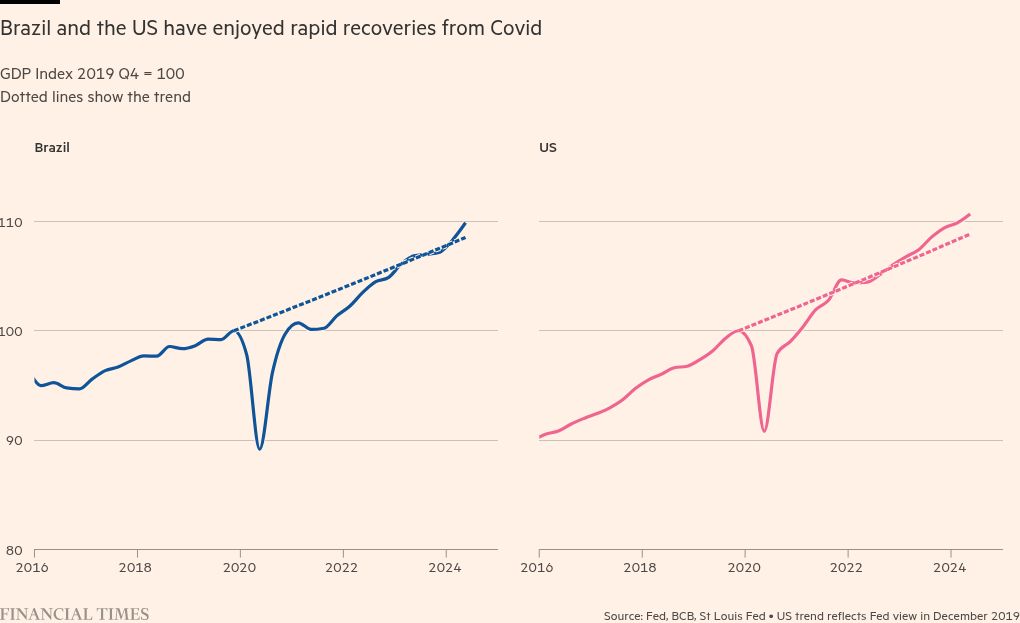

You do not need to look hard to see many similarities between the US and Brazilian domestic economic trends. Unlike Europe, China or Japan, both countries have enjoyed sharp upgrades to their 2024 growth forecasts after economic data showed that initial caution could be discarded. In Brazil, the BCB expects household and government consumption to contribute more to growth this year than it did in early summer. Stronger growth will suck in more imports. US consumption, both household and government, has been similarly strong.

These rises in growth forecasts put the Brazilian economy in a position where the central bank thinks there is a little excess demand. It produced the chart below in its latest inflation report. The Federal Reserve does not produce a similar chart, but if I compare US GDP with the Fed’s pre-Covid long-term sustainable growth assumption, that also shows a similar small level of excess demand.

Both the Brazilian and US governments are often accused of lax fiscal policy. This is of some sensitivity for central bankers in Brazil, with the BCB making oblique references to the need for greater budgetary discipline in its monetary committee’s latest minutes; there is no reference to this in the Fed’s. The IMF’s latest fiscal deficit projections showed a general government deficit of 6.5 per cent in 2024 for both Brazil and the US and a much larger primary deficit in the US. Clearly, there is greater scrutiny and financial market focus on the deficit in Brazil than in the US.

The similarities show strong economic activity in both economies which, on some measures, show excess demand and rising inflationary pressure.

Differences

Of course, just presenting a few economic features that are similar does not make a convincing analysis. Brazil and the US are fundamentally different economies and simple comparisons are hopelessly naive.

At the moment, the two relevant central banks view their economies quite differently. While the BCB sees excess demand, the Fed has largely accepted the stronger-than-expected performance of the US economy as a productivity boost and not inflationary. This comes from the Fed’s assessment of the US labour market, which it no longer sees as tighter than normal.

The US also does not face any financial market pressure to tighten monetary policy, with markets in line with the Fed’s interest rate projections from its September meeting, showing four quarter-point cuts overall in 2024 and 2025.

Core inflation trends have been similar with the rate remaining sticky in both countries and ticking higher in the latest data, but the Fed thinks this is just a blip while the BCB is more nervous. Inflation expectations in the US are also benign while they have been increasing in Brazil.

Comparing the two economies is useful, however, since Brazil is clearly ahead of the US in its economic cycle. While there is no direct read across, it should serve as a reminder about how quickly things change.

In May, the debate in Brazil was all about how quickly to cut rates. Four months later, BCB was unanimous in its vote to raise them.

A political canary

It is not just in policy where Brazil has some interesting parallels to draw with the US: the relationship between politics and the central bank offers some pointers for the consequences of the US election and a second term for Donald Trump.

Since he was narrowly re-elected president in October 2022, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has regularly been at loggerheads with the central bank, pressuring it to cut rates. He gradually changed the composition of the monetary policy committee with new appointments and regularly criticised the BCB for its unwillingness to cut rates.

This came to a head in the spring. At the May meeting, all four members of the BCB monetary committee appointed by Lula voted for a larger cut in rates than the five members appointed by his predecessor, Jair Bolsonaro. Accusing the current governor, Roberto Campos Neto, of political bias against Lula, his Workers’ party filed a lawsuit, requesting that the governor be banned from making political statements.

In summer, Lula appointed a political ally and former deputy finance minister Gabriel Galípolo as the next central bank governor. Galípolo was already on the monetary committee.

He was confirmed by the Brazilian Senate last week. What was notable was the transformation of Galípolo that took place once he was poised to take over from Campos Neto as governor. Galípolo suddenly became more hawkish, saying over the summer that he would do whatever it took to battle inflation. Lula also stopped railing against high interest rates.

The vote to raise rates in September was unanimous, with Lula saying that if Galípolo thought tighter monetary policy was needed, it probably was.

The optimistic lesson for the US is that leaders like to have their people in charge of institutions, and stop interfering once this has happened.

Will this happen with Trump? Email me: [email protected]

What I’ve been reading and watching

-

The on-off story of the great China fiscal bazooka is delayed again. The latest hiccup happened on Saturday when the Ministry of Finance said the National People’s Congress needed to rubber stamp the government’s decision

-

Both Andy Haldane and Martin Wolf want Rachel Reeves to boost UK growth in her Budget. Achieving this desired outcome is harder urging an expansionary policy, as becomes obvious when you read Wolf

-

Robin Wigglesworth investigated whether the US financial system no longer has excess reserves in its banking system. His conclusion was that less comfortable and less liquid times are perhaps already with us

-

Will Congress stop Donald Trump upending the global trading system? Alan Beattie is pessimistic

-

Former Fed vice-chair Richard Clarida has a hunch that the neutral rate has risen a bit. That this is good news for investors in bonds is the not-very-surprising conclusion from Clarida, who now advises the fixed income firm Pimco

A chart that matters

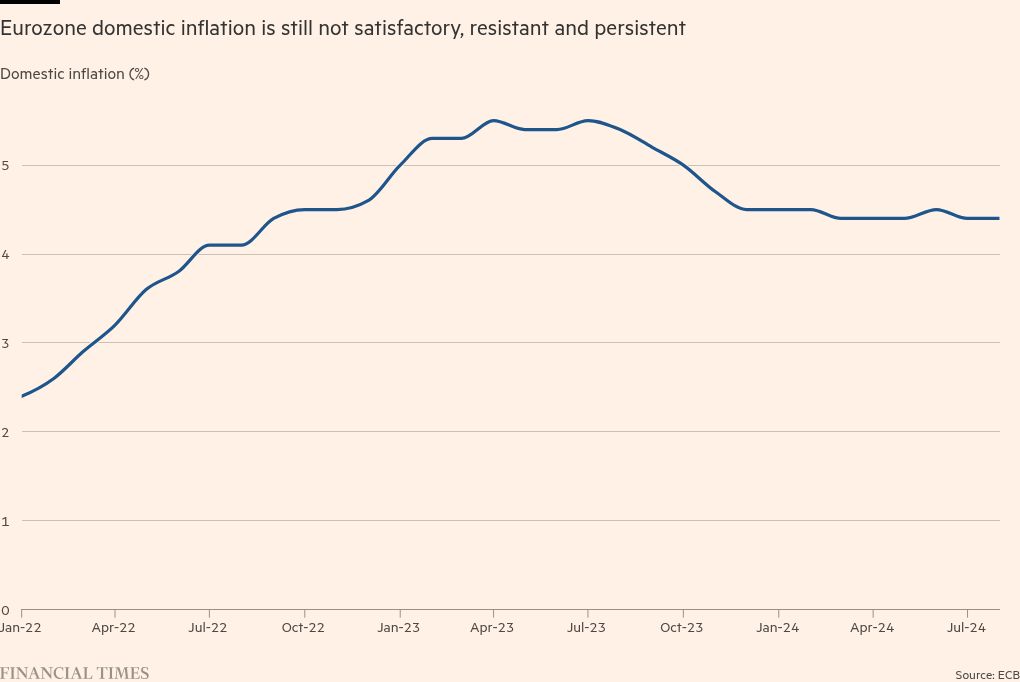

When the European Central Bank cut interest rates in September, President Christine Lagarde said the governing council would be data dependent and had not decided on how quickly to reduce rates further.

She gave a considerable clue that at the time she was not minded to cut again in October. Telling people not to read too much into falling inflation in September, she said Eurozone domestic inflation was troubling her because it was not falling sufficiently. “It is not satisfactory. It is resistant. It is persistent.”

A month later domestic inflation is still not satisfactory, and is resistant and persistent, having not fallen in the latest data for August. Nevertheless, the ECB appears likely to cut rates on Thursday.

It will be interesting to hear from Lagarde her latest view on domestic inflationary pressure and why this measure has been superseded in importance by other data.

Recommended newsletters for you

Free lunch — Your guide to the global economic policy debate. Sign up here

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here