Alex Salmond, who has died at the age of 69, was the central figure in the rise of modern Scottish nationalism, a political heavyweight who as leader of his ancient nation sent tremors through the constitutional foundations of the United Kingdom.

Salmond’s tumultuous career took him from the fringes of Scottish politics to its apex as first minister from 2007 to 2014 — and later, as leader of the minor Alba party from 2021, back to the fringes again.

His greatest achievement was also his most high-profile political defeat: Scotland’s 2014 independence referendum. While Scotland’s voters backed staying in the UK, the 55-45 per cent margin was much smaller than opponents had expected, laying bare widespread disillusionment with the three century-old union with England and leaving its long-term future very much in doubt.

Alexander Elliot Anderson Salmond was born on Hogmanay — as New Year’s Eve is known by Scots — in 1954 in Linlithgow, a royal burgh that has a ruined Renaissance palace at its heart and is steeped in history from Scotland’s days as an independent kingdom. Brought up in a modest council house, Salmond as a boy heard from his grandfather stirring tales of how local families joined the bloody 14th-century resistance to English rule — stories he would later say “kindled a flame” of patriotism that was to guide his political life.

But while Salmond would relish a stirring historic quote or poem, he was no simple romantic. At the University of St Andrews — where he joined the Scottish National party, then a marginal force in the nation’s politics — he paired the study of medieval history with that of economics. In 1980 he joined Royal Bank of Scotland where he worked as an economist for seven years, acquiring a deft if somewhat slippery grasp of statistics that would later help him argue the difficult economic case for independence.

He established himself as one of the SNP’s rising stars, pushing for the party to make itself more electable in western and central Scotland by adopting more socialist policies. Briefly ejected from the party in 1982 for his role in a republican faction, he was a few years later able to successfully contest the Banff and Buchan constituency in north-east Aberdeenshire at the 1987 UK general election.

The novice MP soon found a way to establish himself as a serious presence with a move that combined his tactical skills, self-belief and penchant for provoking the establishment. In a carefully planned disruption of the Conservative government’s 1988 Budget speech, Salmond stood up to denounce its introduction of a widely hated flat-rate local poll tax — a breach of protocol that won him and the SNP huge publicity.

Elected party leader in 1990, he pursued a pragmatic approach to independence aimed at minimising nervousness among voters about the risk of leaving the UK, abandoning previous opposition to EU membership in favour of calls for “independence within Europe”. He also sought to widen the SNP’s appeal, reaching out in particular to Catholic and Muslim groups and committing the party to an inclusive and broadly progressive model of civic nationalism.

The creation of a devolved Scottish parliament in 1999 gave the SNP a vital new venue to wield influence, but Salmond was at first less comfortable there than in clubby Westminster, stepping down as leader in 2000 and quitting the new Edinburgh chamber a year later. The party struggled in his absence, but when he returned as leader in 2007 it won a historic victory to become the Scottish parliament’s largest party.

Even opponents acknowledged the competence and discipline of the minority administration Salmond led as first minister. In 2011 voters rewarded him with an unprecedented parliamentary majority that the UK government recognised as a mandate for the SNP’s central manifesto pledge: a referendum to undo the 1707 union of the Scottish and English parliaments that lies at the UK’s constitutional heart.

The resulting campaign was a crowning moment for a politician who always had, as Scots like to say, a “guid conceit of himself”. Pro-union politicians struggled to counter his energetic and positive, if Pollyanna-ish, campaign for a “Yes” vote. While fighting the “nationalist” corner, the vision of independence offered by Salmond’s SNP took a more subtle view of sovereignty — including continued membership of the EU, and the sharing of currency and monarchy with a rump UK — than did his pro-union opponents.

While UK minister Michael Gove fretted that independence would make family members into foreigners, for example, Salmon blithely assured voters the British “social union” would remain intact. “We are bound to the other nations of these islands by ties of history, culture and language; of trade, family and friendship,” he declared.

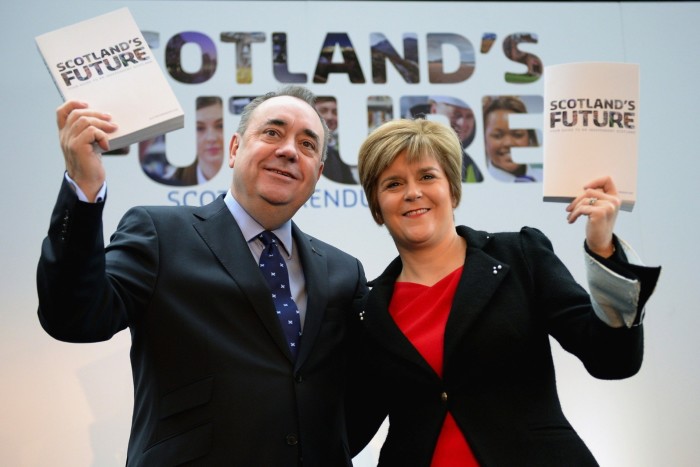

The referendum defeat was a bitter disappointment, but Salmond’s quick resignation as SNP leader at first appeared a master stroke that cleared the way for the succession of his then-wildly popular protégé Nicola Sturgeon, and an SNP landslide in the UK general election of 2015.

Instead it turned out to be the beginning of a dark third act in Salmond’s political life. He was furious when after a return to the UK parliament he lost his seat in 2017, blaming what he considered an SNP campaign mismanaged by Sturgeon. Many former supporters were deeply dismayed when the former first minister — who had long railed against what he called biased coverage by mainstream media and the BBC — launched a political talk-show on Kremlin-backed Russian broadcaster RT.

In 2018, two civil servants used a procedure brought in by Sturgeon’s government to file formal harassment complaints against him dating from his time as first minister. The Scottish government later accepted that its resulting investigation was “tainted by apparent bias”, but it sparked a police inquiry that led to charges including attempted rape and sexual and indecent assault and, in March 2020, to what local media dubbed Scotland’s “trial of the century”.

Salmond was acquitted on all 13 charges against him. On 12 charges the jury found him not guilty. The other, of sexual assault with intent to rape, which stemmed from a late-night incident at Salmond’s official residence, was found “not proven” — a verdict unique to Scots law that has the same legal effect as “not guilty” but is often considered to signal doubt on the part of jurors about a defendant’s innocence.

During the trial, Salmond’s lawyer accepted that the former first minister had acted “inappropriately”, saying in court that “if the first minister was a better man I wouldn’t be here, you wouldn’t be here, none of us would be here”. Salmond himself said that he had two drink-fuelled sexual encounters with two much younger and more junior colleagues at his residence, but that they were entirely consensual.

After the trial, he was unapologetic, insisting it had vindicated him as the innocent victim of a conspiracy organised by the institutions led by his chosen successor. “The evidence supports a deliberate, prolonged, malicious and concerted effort among a range of individuals within the Scottish government and the SNP to damage my reputation, even to the extent of having me imprisoned,” he told a parliamentary inquiry in 2021.

Voters have appeared unsympathetic, however. In 2021, he launched a rival pro-independence Alba party, named after the Scots Gaelic for Scotland, but despite his gradually increasing media profile, it has had little electoral impact.

Divisions in the independence movement and an ongoing scandal over the SNP’s use of donations have left Salmond’s independence cause in disarray.

But Salmond always insisted that, as he put it in the hours after the referendum defeat, the independence dream “shall never die”. The former first minister, who is survived by his wife Moira, a former senior official in the Scottish civil service 17 years his senior, was active to the last. On Saturday he posted criticism of current SNP leader John Swinney on social media just hours before his collapse and death in North Macedonia.

While polls suggest support for the SNP has fallen and backing for Alba is very low, they show nearly half of Scots still support leaving a union that is struggling to prove its value to its smaller nations. The constitutional touch paper that Salmond helped light is burning yet.