In court, it’s usually the defendants who apologise to the judges. But at Snaresbrook Crown Court in east London, the roles have been reversed.

“I’m so sorry,” Judge Charles Falk tells a man charged with sexually assaulting a neighbour while they walked their dogs together. “I shouldn’t be having to say this, but that’s the position in the court at the moment.” The reason for Falk’s apology is time: the man’s trial will not begin until May 2026, two years after the alleged offence. This is despite the case being designated “high priority”.

What about cases that are only “medium priority”? A luxury hotel worker walks to the dock, accused of grabbing another man’s buttocks in the toilets of a Canary Wharf shopping centre. It doesn’t seem the most complex matter to resolve, but after pleading not guilty, the defendant is told the earliest available trial date is November 2026.

“I’m terribly sorry,” Falk says. “I recognise that your life is on hold.” The apology is incongruous, juxtaposed with stern warnings about sanctions for not turning up to trial. The alleged victim is not in court, but the judge asks the prosecution to provide him with all the support possible.

So these defendants and victims learn what barristers have said for years: the criminal justice system of England and Wales is blocked and probably broken. Public debate focuses on whether the police will catch criminals and whether the courts will sentence them correctly. But lawyers are increasingly concerned about the bit in the middle, the part of the process that rarely features in TV thrillers: the slow wait for court time. In early 2019, there were 33,000 cases outstanding in the Crown Courts. By the end of 2023, there were nearly 68,000 — a record.

There are no up-to-date figures because embarrassingly the Ministry of Justice has discovered problems with its data. But almost no one thinks the audited numbers will be better. “We’re drowning in cases. It’s totally unmanageable,” says Max Hardy, a criminal barrister. “The government inherited a crisis in our criminal justice system,” says the Ministry of Justice.

If justice delayed is justice denied, then English courts are regularly denying justice. And the worst effects may only be felt in the next few years — as prosecutions finally come to trial, only to fall apart because witnesses’ memories have corrupted with time. Barristers told me that defendants are less likely to plead guilty because they see the prospect of conviction as remote. Meanwhile, victims are deciding not to pursue complaints.

Convincing a jury that a rape victim is telling the truth, and their attacker is lying, is hard enough. It becomes harder if, because of the passage of time, the victim seems less sure of the details. Delays are not just an inconvenience, says the charity Rape Crisis: for some victims and survivors of rape, “there are profound, life-changing consequences”, including the risk of suicide attempts.

Justice sometimes seems swift: nearly 500 people involved in anti-immigrant riots in July and August have already been sentenced. But those cases were exceptional. The authorities wanted quick justice to help end the riots (it helped that many rioters pleaded guilty). Since 2019, the average time between a crime happening and the Crown Court case ending has gone from 16 months to 22 months.

It’s not just the courts to blame. At Snaresbrook, a man appears in front of Judge Falk. He is accused of trying to rape a girl at her 15th birthday party, when he was 16. The alleged offence was in 2018. The girl went to the police in 2019. But this day — in September 2024 — is the first court hearing.

Somewhere, between the police and the Crown Prosecution Service, the investigation has gone terribly wrong. “Why does a case of this nature take six years?” exclaims Falk. “What’s a jury going to make of something that’s so old?”

The courts, like in the health service, are seeing a fundamental break with expected standards. Those involved want more funding. Without it, the choice seems to be between stagnation and a radical shake-up.

Between 2009/10 and 2022/23, the justice budget for England and Wales fell 22 per cent per person in real terms, while overall government spending rose 10 per cent. David Cameron’s pledge to fix the roof while the sun was shining feels especially hollow in a dilapidated court with a leaking roof and no heating. But his calculation was political. Most voters wouldn’t go to a court. And they certainly wouldn’t set foot in Britain’s even more crumbling prisons, as rehabilitation became an ever more distant prospect.

The Conservatives’ calculation was also technical. As violent crime dropped in the 2010s, in Britain, as across many western countries, there seemed to be less need for criminal courts. The government cut barristers’ fees and sold off court buildings: 43 per cent of courts were closed after 2010. (One of these, Blackfriars Crown Court, was later used to film courtroom scenes for Netflix drama Top Boy.) But the number of cases awaiting trial still fell.

Before the pandemic, the then Lord Chief Justice Lord Burnett warned that things had gone too far. Ministers disagreed. In early 2019, the backlog started to rise, as Burnett predicted. Then Covid hit, the courts were closed, and the backlog jumped (even though crime also fell during the pandemic). A strike by barristers over pay worsened the situation.

No one had planned for the pandemic. But ministers also hadn’t planned for the rise in prosecutions of sexual offences, linked to societal outrage at low conviction rates. Such cases strain the courts: they tend to be complex and defendants tend not to plead guilty. For all criminal cases, the percentage of guilty pleas is about 66 per cent. For sexual offences, it’s 39 per cent. For adult rape cases, it’s just 15 per cent. Between 2019 and 2023, the number of adult rape cases awaiting trial trebled to 2,786.

Ministers also failed to plan for prison overcrowding: this year, some prisons such as Wandsworth had 50 per cent more prisoners than they could decently accommodate. The crises in the courts and the prisons are interlinked. An increasing part of the swelling prison population is made up of people awaiting trial. (By law, defendants should be in custody for a maximum of six months before trial; these limits are now routinely extended.)

In 2022, to reduce the backlog, the Ministry of Justice made more cases triable by magistrates — allowing them to sentence people for offences worth up to 12 months in prison, instead of the usual six. In 2023, it suspended the measure because there weren’t enough prison cells for the resulting prisoners. Even so, Labour is expected to revive that measure: the ministry’s models suggest that the prison population will go up slightly, but the new prisoners can be dispersed around the country, in a way that prisoners awaiting trial cannot be.

Overwhelmed prisons are also a major source of court delays: they fail to produce prisoners for hearings. At Snaresbrook, I saw the court wait in vain for a prisoner to appear via video from Manchester. “It’s just ringing through. They’re not answering,” said the court clerk, phone in hand. The judge sighed: “It’s a comfort to know that it’s not just Pentonville and Thameside that have problems connecting.” Eventually the hearing was abandoned. “There’s nothing I can do without your client. You can hardly plead guilty on his behalf,” the judge told the defence barrister.

262

Days that the Crown Court took to complete a case on average in late 2023, up from 145 days in late 2019

32%

Proportion of outstanding cases that were for sexual offences, as of late 2023

68,000

Cases outstanding in the Crown Courts in late 2023, up from 33,000 cases in early 2019

Judges regularly fume at Serco, the company that is paid £80mn a year to transport prisoners in southern England to court and accompany them in the dock, but that often seems unable to do so. Officially prisoner escort companies meet their contractual obligations 99.93 per cent of the time. Serco and the Ministry of Justice both declined to explain how this is calculated.

I was told a variety of reasons why prisoners don’t turn up, including: Serco lacks enough drivers qualified for 12-seater vans, so has to use small vans that are less efficient; prisoners refuse to come and inexperienced prison officers don’t know how to cajole them; prison staff aren’t sure where a prisoner is in the jail; and prison overcrowding means prisoners are now scattered in different jails. Serco says it is working “under very challenging conditions”, and is trying to recruit more staff.

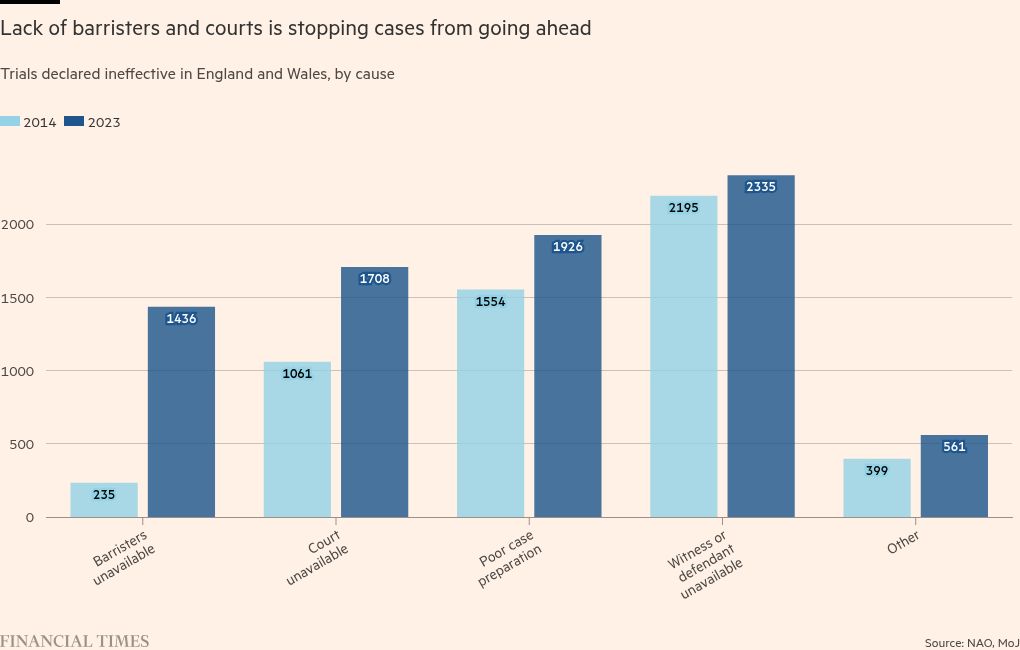

One in four trials now doesn’t go ahead as scheduled. A growing reason is a lack of lawyers. In 2019, only 71 trials were cancelled on the day they were due to begin because a barrister wasn’t available for one side. Last year, the figure had risen 20-fold — to 1,436.

Why aren’t there enough barristers? Crime has long been the worst paid field for advocates. Experienced junior barristers are paid £713 a day for prosecuting a murder (this also covers costs and rent). They earn more doing family cases. If they work on one of the many public inquiries, they can earn £120 an hour. So they switch. Those remaining criminal juniors try to do as many cases as possible: “churn and earn”.

As lawyers are overstretched, quality drops. “People are turning up for hearings constantly and nothing has been done,” one young barrister told me. Psychiatric reports haven’t been requested, witnesses’ telephone data hasn’t been processed, and so on. That is partly due to cuts to the Crown Prosecution Service and legal aid solicitors. The number of criminal law duty solicitors has fallen by a quarter since 2018. In a recent case, a man accused of raping a woman walking home from a bus stop was allowed out on bail for a year because the CPS had made so many errors in prosecuting; he was later convicted.

In the courts, as elsewhere, cutting budgets can be expensive. The Ministry of Justice now accepts that cuts to legal aid ended up costing the taxpayer because of the wasted time produced by defendants not having early legal advice. Faced with a lack of court space after Covid, the government set up temporary Nightingale courts. To run a normal courtroom costs, on average, £280,000 a year. To run a Nightingale court costs between £440,000 and £1.6mn a year; 18 are still going.

Under Boris Johnson and Rishi Sunak, the government did pump extra money into the courts, but it has not been enough. “In cabinet, I found myself having to remind colleagues that England and Wales has the second-largest legal sector in the world. It came as a surprise to people who were otherwise very well informed,” says Alex Chalk, justice secretary under Sunak.

Frustrated criminal barristers argue that the fame of England’s criminal courts underpins the thriving commercial legal industry. One told me that big commercial law firms should be taxed to pay for improvements to criminal courts.

In a significant way, courts today are different and probably much better: video links, which did not exist before Covid, are now commonplace. Thanks to technology, barristers can hop between different Crown Courts in a single morning, and prisoners don’t have to be taken by secure vehicle at a cost of hundreds of pounds. But these efficiencies have not saved the system.

What more could be done? Before he stepped down as lord chief justice last year, Lord Burnett pushed for something more radical — removing the right for defendants to have a jury trial for some offences. Currently, there are some offences, such as speeding, that can only be tried by magistrates, and some, such as murder, that can only be tried by Crown Court judges with juries. There are also some, such as minor theft and drug offences, for which the defendant has the right to choose; most of the time, they choose a jury, because juries are much more likely to let them off. (Assault is an offence dealt with by magistrates, but in 2018 parliament made it a specific offence to assault an emergency worker — one for which the defendant can choose a jury. This now makes up a substantial number of Crown Court cases.)

Jury trials are notoriously inefficient. Shuffling 12 people around the building, explaining the basics of the law to them, accommodating their personal commitments — this all adds time. Trying a case in front of a judge and two magistrates might take, say, half as long. “You’d rattle through cases much more quickly,” says Chalk. Everyone should be entitled to a jury the first time they are accused of dishonesty, “but maybe not the second or third or fourth”. (Rape Crisis, the charity, would go further: it wants judge-only trials for rape cases.)

A similar idea was put forward under New Labour, but failed amid an uproar about the sacredness of jury trial. “Trial by jury is a bit of a red line. Just because they’ve run the system into the ground doesn’t seem like a very good reason [to cross it],” says Will Paynter of 15NBS Chambers. Like most criminal barristers I spoke to, he wanted more resources: more courts, open for more days, and more funding for barristers and solicitors to do the work.

The Bar Council, which represents barristers, has called for fees to rise 15 per cent and for the government to match-fund 100 extra criminal pupillages a year. Fixing the courts would cost maybe £2bn a year — maybe not “huge sums compared to other public services”, says its chair Sam Townend. Townend adds that barristers’ mood is “expectant and cautiously hopeful. We have a prime minister and an attorney-general who have been practising barristers.”

Sir Keir Starmer is said to take a close interest in courts policy. But neither he nor justice secretary Shabana Mahmood mentioned the backlog in their speeches to Labour conference. The mess in prisons has taken priority. Labour’s pledge of specialised “rape courts” has remained sketchy.

As with other public services, much hinges on this month’s Budget. A key metric for lawyers is sitting days — one sitting day is one courtroom functioning for one day. The Conservative government had agreed 106,000 sitting days this year. To bring down the backlog, judges pushed for the courts to run at full capacity: 6,000 more days, with inevitable extra costs. Mahmood agreed only to an extra 500. In response, the senior presiding judge warned two weeks ago that “a very large number of trials and other hearings that are scheduled to be heard will now have to be rescheduled”.

Meanwhile, at Snaresbrook when I visited, three courtrooms were sitting unused, and Judge Falk would book in a serial offender on drugs charges for a trial — in January 2027.

Henry Mance is the FT’s chief features writer

What should it take to convict a criminal?

The eviction of an intruder from Janine Gibson’s home was just the start of a long legal battle. Read

Find out about our latest stories first — follow FT Weekend on Instagram and X, and subscribe to our podcast Life & Art wherever you listen