This article is an on-site version of our Inside Politics newsletter. Subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday. If you’re not a subscriber, you can still receive the newsletter free for 30 days

Good morning. When Harold Wilson, the Labour leader whom Keir Starmer has said he admires most, was elected in 1964, he did so promising “a hundred days of dynamic action”. Instead — and I promise I am not making any of this up — his government swiftly got into political difficulties.

The administration had underperformed the polls. It entered government but with fewer votes than it had got in its very bad defeat in 1959. There was a general sense that Labour hadn’t won the election, rather the Tories had lost it. Nicholas Kaldor, one of the experts that Wilson brought in as newfangled “special advisers”, a Wilsonian innovation, attracted a great deal of media attention, not all of it favourable. A decision to limit a benefit only to some of the poorest pensioners (again, I am not making this up!) made the Labour government very unpopular with the oldest voters and triggered the first serious rebellion of the new Labour government’s life.

And on the 99th day, the Labour government lost the Leyton by-election to the Conservatives, halving the government’s minuscule majority in the process. It had been a safe Labour seat since its creation. “It was an awful evening,” Richard Crossman, one of Wilson’s closest cabinet allies, wrote in his diary, “I felt an epoch had ended — ironically enough this was the ninety-ninth day of Harold’s famous Hundred Days.”

Wilson’s biggest achievement, really, was to inject the idea of the “first 100 days”, an otherwise pretty meaningless milestone, into Westminster’s collective imagination.

It is the 99th day of Starmer’s government, and while he has not had his Commons majority halved thanks to by-election defeat, he has, in many ways, enjoyed a similarly bruising start to life.

On the bright side for Labour, this very familiar story has a happy ending for them at least, in that the Wilson government was re-elected two years later with an increased majority (it even won back Leyton). Will history repeat itself? Some further thoughts on the differences and similarities between now, then, and incoming governments in general, alongside some exclusive polling from Ipsos.

Inside Politics is edited by Georgina Quach. Read the previous edition of the newsletter here. Please send gossip, thoughts and feedback to [email protected]

Starmer’s got 99 problems, Badenoch ain’t one

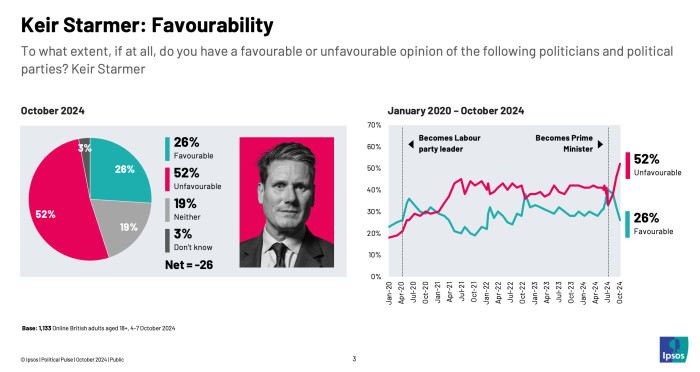

How are Keir Starmer’s ratings doing after 99 days in office? The only word that comes to mind is “badly”.

Now, the joy of Ipsos is that its polling goes back far enough that we can compare this with three first-term prime ministers: Tony Blair, Margaret Thatcher and David Cameron. The bad news for Starmer is that he is polling worse in absolute terms than all three of them 99 days in.

The good news for Starmer is that at this point in 1979, Margaret Thatcher was trailing Jim Callaghan, the Labour leader she had defeated 99 days earlier, by 16 points (his net satisfaction score was +18, hers +2). Rishi Sunak, the Conservative leader Starmer defeated, still trails him by 10 points.

Just like Callaghan in the summer of 1979, Sunak is soon to be replaced by another Tory. But, like Callaghan in 1979, Sunak is not going to be replaced by a leader who is well-placed to do better than him. Neither Kemi Badenoch nor Robert Jenrick perform well in focus groups, and their first public appearance saw both of their ratings go down.

Historically, elections have always been about the relative strength of the choices on offer — at no point in the 2019 election was Boris Johnson anywhere near as popular as Theresa May in 2017. But he was considerably more popular, or rather, significantly less unpopular than Jeremy Corbyn was in 2019. It seems unlikely, to put it mildly, that Starmer is going to face a Conservative leader who is a better face for the Tory party than Sunak or one who will repair the damage to its standing and prestige.

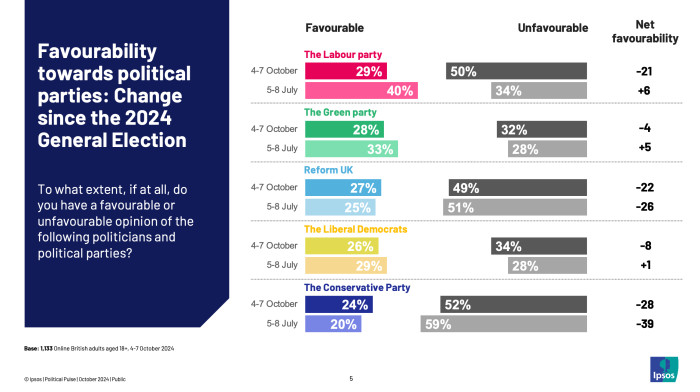

There’s another striking thing here. It is not just the Labour party whose approval ratings have declined over the past 99 days — so too have the Liberal Democrats and the Greens. Now, it is true to say that all three parties of the centre, centre-left and left have different political traditions, and slightly different support bases. There are Lib Dem-held constituencies that Labour could never win, there are Green seats that Labour could never win, and there are Labour seats that one or both of the Liberal Democrats and Greens couldn’t win. But perceptions of all three parties are linked in most voters’ minds, and although that might change, it hasn’t yet.

Now, of course, what really matters in terms of the next election is how Labour governs over the next four to five years. How people feel about the alternative government is an important but secondary issue.

Labour, like most new governments, is having a difficult start. But most governments have found their feet after two years at most, and thus far, I see nothing to suggest Labour won’t do the same. The new Downing Street structure is attracting favourable reviews for having a clearer direction than the old one. (Though that may just be because Morgan McSweeney used the first all-hands Spads meeting since becoming chief of staff to reassure attendees that their pay issues would be fixed in short order.)

There are real causes for worry about the new Labour government. The promises it has made on tax may cause it to either fall short of public expectations in terms of improving the condition of the public services and/or cause it to raise a bunch of fiddling little taxes that prove to be economically harmful or politically painful.

Most first-term oppositions make dreadful, damaging mistakes and similarly, I see no sign that the Conservative party are about to avoid that. Bob Blackman, the chair of the backbench 1922 committee, has told GBNews that the party wants to change the rules to make it harder for Tory MPs to get rid of their leader, and harder still for them to get rid of the leader in government.

I’ve heard this idea raised by a number of Conservative MPs and it is clearly currently a fashionable notion in the parliamentary party. But more importantly it is a really, really, really stupid idea.

One of the Tory party’s historic advantages over the Labour party is that Labour makes it really difficult to get rid of its leaders, which means it has almost always had to get British voters to do it for them. The Conservative party’s ability to change its leader enabled Boris Johnson to swiftly take charge, renew the party and allow it to win in 2019. It meant that Michael Howard led the Tories into the 2005 election not Iain Duncan Smith. It meant that former Conservative prime minister John Major won a fourth term, one that safeguarded the policy achievements of Thatcherism, which would otherwise have been swept away by Labour’s Neil Kinnock. It meant that Alec Douglas-Home, who took over as Conservative leader after Harold Macmillan’s sudden resignation, fought Wilson to an extremely close result in 1964. It meant that Macmillan won the 1959 election after the Suez crisis.

And frankly, it also meant that the Conservatives avoided going into the 2024 election led by the prime minister who oversaw lockdown-breaking parties in Downing Street or the prime minister who oversaw a self-made financial crisis. Whatever mistakes Rishi Sunak made as prime minister, he was certainly a better bet electorally than Liz Truss and in my view probably a better one than two more years of scandal and drift with Johnson.

To dismantle that big institutional advantage would be the biggest act of political self-sabotage since, well, this Wednesday.

Broadly speaking, parties do well when they learn from the other lot’s successes. Keir Starmer fought the 2024 election on similar territory on which Johnson won the 2019 one. David Cameron and George Osborne aped much of the style and approach that helped renew the Labour party in the 1990s. Even Margaret Thatcher, who represented a radical breach with the politics of the 1970s, spruced up her own personal image by borrowing from the woman who was then the most popular female politician: Barbara Castle.

Ninety-nine days in, a Labour party that is finding its feet is still clearly keen to learn from the Conservatives who had previously beat it. The Conservatives meanwhile are emulating Labour in the 2010s and 1980s. There are 1,768 days until the absolute last date of the general election, and much can change between now and then. But as it stands, both Labour and the Conservatives look to be doing the usual things that first-term governments and first-term oppositions do, and as such, they are both probably heading for the usual result that first-term governments and first-term oppositions get.

Now try this

I’m off next week to catch up on sleep and to do a bit of a gallery crawl, but Inside Politics will continue with an exciting cast of guest writers. However you spend it, have a wonderful weekend!

Top stories today

Recommended newsletters for you

US Election Countdown — Money and politics in the race for the White House. Sign up here

One Must-Read — Remarkable journalism you won’t want to miss. Sign up here