This article is an on-site version of our Europe Express newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday and Saturday morning. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good morning. News to start: The US is working on plans to participate in a $50bn G7 loan to Ukraine even if the EU fails to meet a demand to adjust its related sanctions, officials told us.

Today, Laura reports on potential plans to house EU immigrants in neighbouring countries, and I question whether, among the Eurosceptic bluster, Viktor Orbán may have a point about EU hypocrisy on Russia.

Have a wonderful weekend.

In the neighbourhood

In their quest for “innovative solutions” to bring down migration numbers, EU countries are considering asking neighbouring countries — for instance in the western Balkans — to take in unwanted immigrants, writes Laura Dubois.

Context: Migration has climbed high up the EU agenda, as several countries complain their asylum systems are overwhelmed. A recent EU asylum reform will only come into force in 2026, prompting creative capitals to single out third countries to take on the problem.

Such deals with third countries are fraught and expensive, as the recently-abandoned UK plan to send asylum seekers to Rwanda showcases. But more and more EU countries are warming up to those schemes, especially after Germany signalled it would no longer exclude them.

“This is very high on the political agenda today,” Sweden’s migration minister Johan Forssell told journalists yesterday, saying that all his conversation partners from Socialists to the centre-right European People’s party agreed the topic of migration was urgent.

Home affairs ministers yesterday discussed how to increase returns, as the EU struggles to send people whose asylum applications have been rejected back to their home countries — often because those countries do not accept them back.

One option discussed by the minister were so-called return hubs, where rejected people would await their deportation. “We should not close our door to that,” Forssell said. “I think we are ready now to take that to the next phase.”

The western Balkans was floated as one possible location for such a hub, EU officials said, pointing to Italy’s asylum deal with Albania as a promising example. But the officials also added that more technical work was needed to understand whether the hubs were legally feasible, and which country would consent.

Ministers yesterday also urged the European Commission to update a dedicated law on returns that has so far remained stuck in the European parliament, the officials said.

“We want to have stricter legislation on what you are supposed to do as an individual . . . it’s not voluntary. You need to go back home,” Forssell said.

He added that the EU should also change its tack on countries that don’t take back their citizens, making development aid or trade contingent on accepting returns. “If we are going to co-operate with them, they must co-operate with us,” he said.

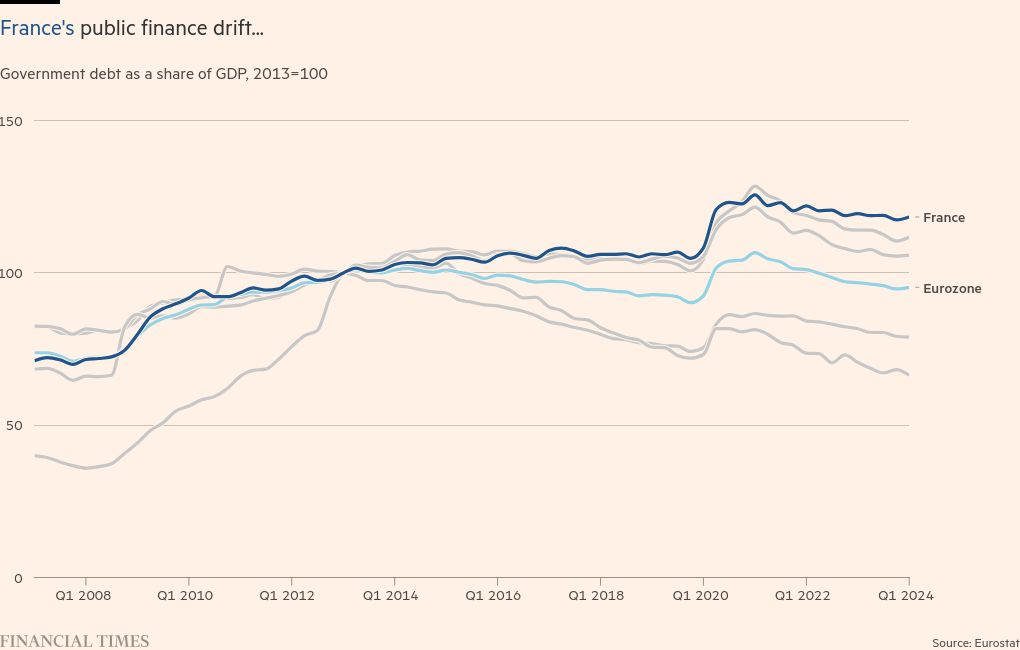

Chart du jour: Shock therapy

France has proposed a budget for next year with around €60bn worth of spending cuts, as it tries to narrow its deficit.

Awkward truths

Viktor Orbán’s European parliament performance this week was mainly political theatre designed to elevate his status as the EU’s bête noire, rev up his populist allies in the chamber and thumb his nose at the mainstream centrist majority.

But he also landed some legitimate punches.

Context: Orbán’s self-styled “illiberal” regime is the EU’s most pro-Russian government. He has repeatedly delayed or blocked support packages for Ukraine and sanctions against Moscow, and endorsed former US president Donald Trump’s demand for an immediate ceasefire in the war.

Orbán on Wednesday rolled out his standard Eurosceptic rhetoric, accusing Brussels of using “political weapons” against him and other rightwing politicians, and calling for “normal” relations with Russia — something European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen rightly skewered him for.

But Orbán’s remarks about EU hypocrisy on Russia struck a nerve.

Criticised by MEPs for his fondness for Russian trade relations, he hit back by claiming that exports of EU goods to “certain central Asian countries” — widely understood to be conduits for Russian imports — are €1bn a month higher than before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, suggesting widespread sanctions evasion.

He also cited research that suggests Russian crude oil purchases by western countries have surged since 2022, earning the Kremlin billions of dollars in additional tax.

And after von der Leyen condemned him for a visa programme used by Russians to enter Hungary, Orbán pointed out that the 7,000 Russians working in his country were dwarfed by hundreds of thousands of Russians working in Germany, France and Spain.

Orbán’s whataboutisms don’t justify his political rhetoric. But his charges of hypocrisy should be taken seriously by mainstream EU leaders who are quick to paint him as the reason why Brussels has not been tougher on Moscow. That may not be entirely true.

What to watch today

-

EU justice ministers meet in Luxembourg.

-

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy visits Germany.

-

Cyprus hosts summit of Mediterranean countries.

Now read these

Recommended newsletters for you

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here

Swamp Notes — Expert insight on the intersection of money and power in US politics. Sign up here

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: [email protected]. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe