Unlock the US Election Countdown newsletter for free

The stories that matter on money and politics in the race for the White House

A “geopolitical risk premium” is a fuzzy concept, roughly equivalent in today’s oil market to an extra $5 charged for each of the 6bn or so “virtual” barrels traded every day.

That the planet consumes (just) 100mn real barrels every 24 hours shows how dominated by speculators the oil market has become. This in turn explains why, alongside the many other obvious catalysts, prices have been as volatile as they have over the past few weeks.

Israel’s exchange of missiles with Iran and the launch of China’s stimulus package meant Brent crude last week notched its biggest five-session gain in more than a year. Prices briefly rose above $80 a barrel this Monday, only to slump 5 per cent on Tuesday after the National Development and Reform Commission’s latest press conference proved a damp squib.

The initial rally was “caused almost entirely by (justified) risk premium,” JPMorgan commodity futures and options strategist Tom Skingsley wrote in a note to clients — but investor “positioning” was a major factor too, he added.

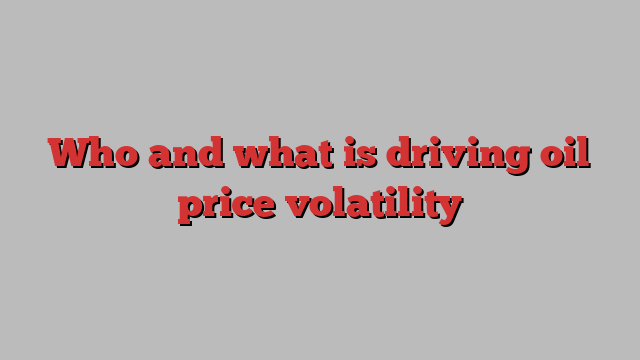

Over the past few months, perhaps the biggest story in oil markets has been algorithmic selling to historic extremes. Net positioning among speculative trend-following hedge funds (aka commodity trading advisors) — which analyse complex technical factors like the term structure of Brent and WTI prices rather than fundamentals like macroeconomics or geopolitics — had, until recently, never been as short.

[Zoomable version]

“CTAs have been a dominant force this year,” Ryan Fitzmaurice, a commodity portfolio manager and strategist at Marex, told FTAV. “Historically there was a lot of sticky money in oil markets, from index managers rolling passive longs and people that were looking for inflation hedges.”

But China’s economic slowdown and the decline in US inflation meant a lot of this “sticky money” deserted the market in April and May. With Opec poised to ramp up supplies in December and global demand looking weak, Brent prices slipped from above $90 a barrel in mid-April to just below $70 by mid-September. Trend-followers, which aggressively buy when prices are rising and aggressively sell when prices are falling, accelerated the sell-off.

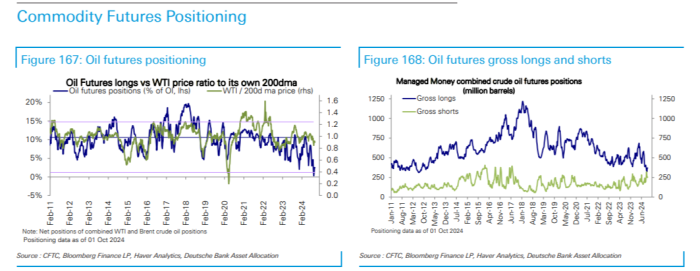

China’s initial fiscal package and escalating tensions between Israel and Iran flipped the market on its head. Eager to hedge their broader portfolios, discretionary investors who for months had watched on from the sidelines began to buy oil futures and call options as a result, snapping the negative momentum that had been driving CTA selling.

The shift in sentiment was hardly profound, explains Ilia Bouchouev, the former president of Koch Global Partners. But it was enough.

Discretionary investors “turned bullish but they don’t really want to buy — they have no incentive to do so before the [US presidential] election,” Bouchouev told us. “If Trump wins and we get tariffs, that’s an extra risk, so why bother putting money on now when they can do the same thing on November 6?”:

A month ago, lots of put options were being bought by producers, and dealers had to sell futures to hedge against this risk. That flow subsided and started to go in the other direction a few weeks ago, when there was suddenly a lot of call option buying from retail investors via ETFs like USO and macro hedgers. There was aggressive buying of $100 calls, as a form of insurance given that no one really knows what will happen in the Middle East. What people do know is that if oil does go to $100, the Fed’s plan would be derailed and other assets would be massively affected.

[Zoomable version]

Momentum-driven CTAs that were “max short” were mechanically forced to cover their positions, Bouchouev added. “Historically, their positions tend to mean revert. So if they’re at one extreme already, there’s no way for them to go but up.”

CTAs are now at 10 per cent, so they have 90 per cent left to go. The issue with CTAs… with momentum, if it’s negative, they will continue to sell. But if the market stabilises for a week or so or you get a small spike, then all of a sudden it breaks this negative momentum. Momentum doesn’t have to turn positive, it just has to stop being too negative. That’s sufficient for CTAs to start buying back. We don’t have positive momentum right now, but they’re starting to cover all the same.

In the past few days, however, the market has been flipped on its head yet again as fears that Israel might strike Iranian energy facilities have subsided and Beijing disappointed on further stimulus.

Per JPMorgan’s Skingsley, in a note published on Tuesday morning:

Flows on the desk were polarizing throughout much of yesterday, there feels to be an increasing interest from the discretionary community to begin to fade the move at these levels, or at the very least take profit whilst systematic money continues to take the other side of that trade as their extensive short continues to unwind…

With that in mind, where next? Still very hard to call until we get some definitive action from Israel but given the extent of the rally we have seen and the fact it has been caused almost entirely by (justified) risk premium and positioning, should the Israeli response ‘disappoint’ (read not impact oil balances/target nuclear facilities) there is now significant room to the downside from here and the risk reward for such a view that was non-existent a week or so ago is much more existent right now…

Some interesting parties have joined in on the selling, according to research analyst Martha Dowding and market design expert Jorge Montepeque — both of whom work at Onyx Capital Group, a liquidity provider for oil derivatives which has almost certainly made a killing from all of the recent volatility.

Trafigura, TotalEnergies, people like that have been selling [on Tuesday]. Exxon has been on the sell-side for a couple of months. They’re reading fundamentals and selling their surpluses, but they could turn buyers whenever. Total flips from buyer to seller every few weeks…

[On Tuesday] Austrian group OMV sold a north sea cargo, Ekofisk, to Total. And BP sold something like 700,000 barrels to Mercuria. OMV isn’t a typical seller — they don’t typically sell publicly, so this is unusual. It’s also unusual to see Exxon selling for two months in a row.

When the market next flips is anyone’s guess. “It’s a never-ending cycle,” says Fitzmaurice at Marex. “CTAs aren’t necessarily so concerned about Opec or the outlook in the Middle East. They’re just trying to monetise momentum” — geopolitics being simply another number on a screen.