Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

So much for as safe as houses. A shocker of a profit warning from UK housebuilder Vistry, triggered by a newly-unearthed £115mn of costs, will dent this year’s full profits by 20 per cent and lopped as much as a third off the company’s share price early on Tuesday.

Investors’ apparent overreaction was understandable on two scores. While it is in a company’s interest to be conservative on these warnings (and Vistry says the problem only affects its South of England division) the discrepancy only came to light a few days ago. Numbers cannot at this stage be conclusive. These problems tend to be like cockroaches: spot one and you need to get the roach motel out.

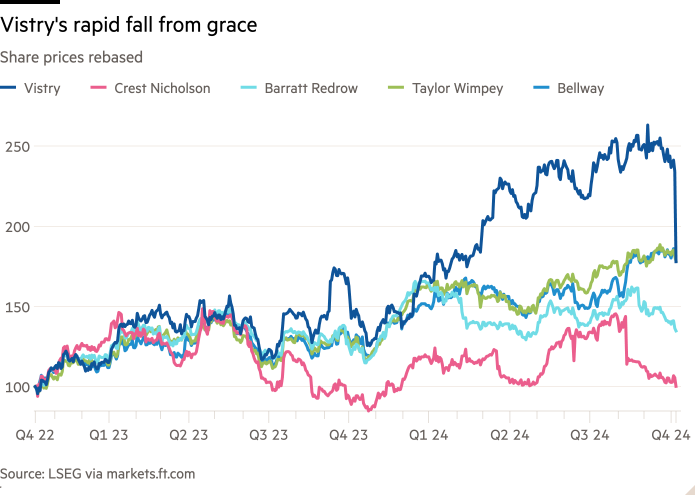

Second, Vistry shares have been on a tear. Investors liked its ambitions, building 18,000 homes this year, with £1bn of shareholder returns earmarked over three years. Until today, shares were up 63 per cent in the past year, almost double the sector. Vistry was trading on 2 times book value, on S&P Capital IQ numbers, compared with 1.1-1.4 times for peers.

Vistry’s premium largely reflected its exposure to affordable housing, a key part of the new UK government’s mandate, and its capital-lite partnership model. But that model, whereby it effectively bulk sells homes to public and private sector institutions, also introduces vulnerabilities.

Regular cash flow from forward sales mitigates the need for wads of capital but it means margins are key. Vistry takes a hit, in short, if a contractor goes bust and has to be replaced with a pricier back-up, or if material costs rise by more than it baked in. No surprise perhaps that the additional costs surfaced at the biggest of Vistry’s six geographic divisions.

Here’s the nub. Retaining the cost risk — Vistry passes “an element” to subcontractors — is not matched by upside from higher house prices given forward selling of homes.

In theory, Vistry’s troubles, which prompted a swift change in the division’s management, are not systemic. But allowing for contingencies while totting up costs should be in these companies’ DNA. Vistry’s earlier iteration, Bovis, has been building houses for the best part of one-and-a-half centuries.

The reality of course is a little different. Vistry would not be the first housebuilder to mess up numbers. Crest Nicholson blamed rising costs at some of its sites among its multiple profit warnings.

Britain’s need for houses, and the government’s pledges to fulfil that need, have helped propel shares in Vistry and its peers higher. But as every homeowner knows, even the best underpinnings don’t stop cracks appearing.