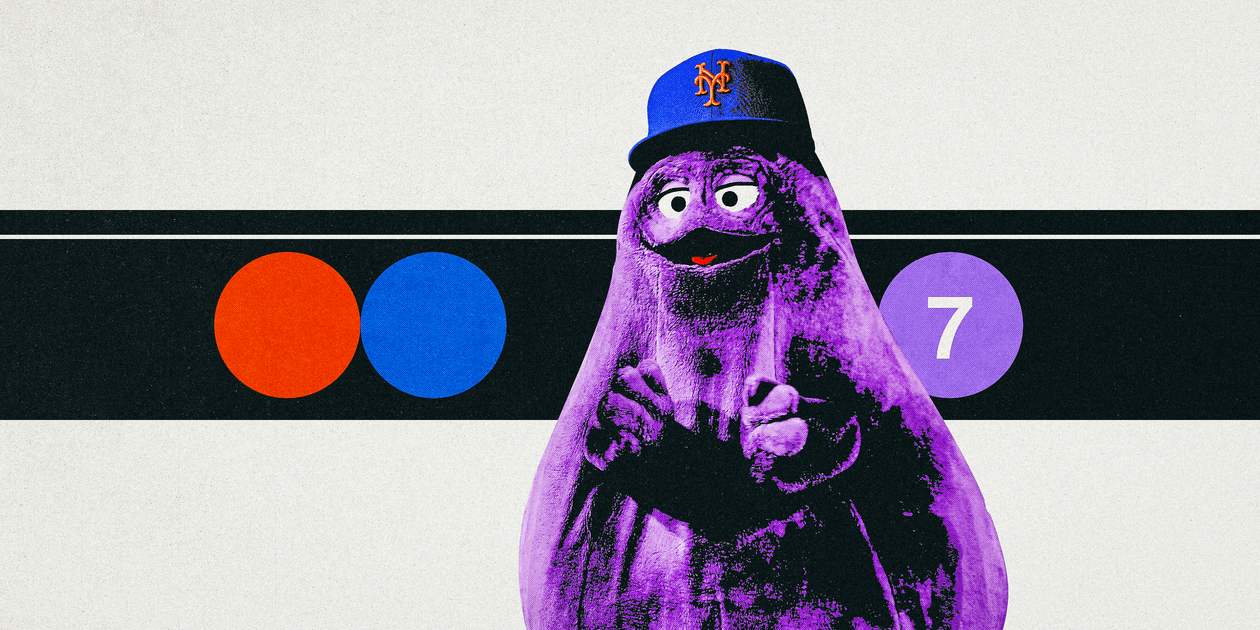

New York Mets fans taking the 7 train to Citi Field Tuesday for Game 3 of the National League Division Series might run into a beloved mascot, while riding on trains draped in its image. Yet the character in question won’t be the big-headed Mr. Met, the stalwart of the baseball mascot circle who was first drawn up in 1963 — but Grimace, the lumpy, purple cartoon character introduced by McDonald’s back in 1971.

It’s the latest development in a surprising, largely unplanned partnership between the Mets and the world’s most ubiquitous fast food chain, one that has made Grimace into a symbol of this Mets team, and is now enveloping New York City’s subway system. One train (all 11 cars) will feature a Grimace wrap and depart Hudson Yards at 1 p.m., ahead of the 5:08 p.m. game against the Philadelphia Phillies.

“We saw so much social conversation where people were photoshopping Grimace’s face decal on the purple 7 subway train line,” said Amanda Mulligan, director of social media and influencer at McDonald’s. “And so it felt perfect that we could bring some of that Grimace flavor into the commute for all of the Mets fans, knowing that everyone’s going to be riding the 7 train up to Citi Field. There might even be a surprise appearance from Grimace himself on the subway.”

The Mets-Grimace connection has its beginnings in a fortuitous ceremonial first pitch thrown by the character at Citi Field on June 12. By most standards, the toss wasn’t good, although it was commendable for someone in such a bulky outfit. More importantly, it preceded a Mets win streak — or some would say, ignited it.

Social media took off, and a McDonald’s-Mets partnership grew to the point that a purple seat was installed at Citi Field in September.

The Grimace seat now occupies a place of honor at Citi Field. (Dustin Satloff / Getty Images)

“From a brand standpoint, I’ve seen it lift our overall awareness and our overall top-of-mind not just attention, but I would say, sort of passion and love for the brand,” said Andy Goldberg, the Mets’ chief marketing officer. “Because we’re bringing two things together that people really have a lot of love for, and also a little quirkiness.”

A relationship between the Mets and Mickey D’s did exist previously. McDonald’s had been a Mets sponsor for at least 10 years, per Brenden Mallette, the team’s senior vice president for corporate sponsorships. And it’s certainly in vogue for various brands to link up — a shorthand has even developed using one company’s name, the letter X, and then the second company’s name, e.g. Mets X McDonald’s. But the odd yet fruitful pairing that has emerged over the last four months is ultimately not something either party was able to fully design.

“If we could do this frequently, I think we would love to, but then it might not be as special, right?” Mallette said.

If the Mets hadn’t embarked on a seven-game win streak the day of Grimace’s first pitch, likely none of this ever happens. But even once that occurred, executives involved emphasized that the “Grimace effect,” as it’s been dubbed, really wasn’t their creation.

The Grimace Effect 🟣 pic.twitter.com/aRBKkMFEwZ

— x – New York Mets (@Mets) June 18, 2024

Once fans jumped on the first pitch, the team and the restaurant chain actually chose to slow-play things, to see where the social media winds would blow.

“When we first started to see the momentum that the fans were getting behind it, we quickly realized, ‘Let the fans take this over. Let the fans do what they do,’” Goldberg said. “As someone on my team said, ‘Let the internet, internet,’ which I thought was a great way to put it. … It’s not ours. If we force it, it becomes really inauthentic.”

Goldberg heeded that advice from Brielle Speranzini, the team’s senior director for integrated brand marketing. The team has sprinkled in Grimace here and there. When the 2025 schedule was released, Grimace appeared in a promotional video, for example. But the Mets seem to have avoided a force-feed, all the while the players keep winning on the field.

“What was so surprising for this one is the continued positivity we saw around the conversation,” Mulligan said. “Our concern the whole time and during the first winning streak was, ‘OK, if this ends, are people going to place blame on Grimace? Are they going to turn on Grimace?’ And we didn’t see that. We kept seeing so much positive conversation of people wanting to bring grimace back for the first pitch again, and wanting to reignite that winning streak.”

Cross-promoting IP comes with some nuances. When Grimace visits town, McDonald’s doesn’t just ship a giant purple costume to the park. One of the usual actors who plays Mr. Met isn’t moonlighting in a Mickey D’s outfit for the day.

No, Grimace has to be specially brought in, and doesn’t arrive alone.

“I’ve met Grimace,” Goldberg said. “I have not met the person in Grimace. He comes as costume, and the person who plays him, and a handler. And from what I understand, there are only two Grimaces in the entire world. They’re very hard to book, but they’ve been very accommodating to us.

“But they do not send the costume. It’s not like, ‘Hey, do what you do.’ Grimace has his own mannerisms, his own way of working, and it is McDonald’s IP and property, and that’s who travels. And it’s a fascinating world, the mascot world.”

McDonald’s representatives did not respond to questions regarding how many Grimaces actually walk the earth, or what it takes to book one. But ultimately, both the Mets and McDonald’s — the latter aided by the public relations firm Golin and the advertising agency Wieden+Kennedy — say the pairing has been valuable for their brands, although neither company shared relevant metrics or dollar figures.

“There’s ways for us to measure the impact of earned conversation,” Mulligan said. “In this case, we weren’t looking at it so much from a business standpoint, but more so just like, this is a completely unexpected thing that happened in culture, and we reacted very quickly, and we just wanted to continue to feel that conversation.”

Not everything the Mets have tried this year has worked quite so well. In August, the team invited Hailey Welch, an internet star who went viral for a sexual joke, out for a first pitch, and were panned by some for the choice. The team has had an aggressive marketing strategy, and believes sometimes, an effort will miss the mark, but will net positive results in the long run.

“That’s exactly it,” said Goldberg, who said the Welch decision “is what it is, and we move on.”

Grimace, meanwhile, keeps on generating positive discussion. Karen Tiber Leland, CEO of New York-based Sterling Marketing, said there’s “always an element of luck and serendipity.” And a quirky connection like burgers and baseball can be mutually beneficial, even if odd at first glance.

“Imagine there’s two rooms, and you send a representative from McDonald’s into a room with 1,000 people, and you send a representative from the Mets into a McDonald’s room with 1,000 people,” said Leland, who’s not working with either party. “They’re each getting to talk to a new room of audience they might not have gotten to talk to, and they’re leveraging the credibility of the company that’s hosting them in that room.”

What becomes of the Grimace effect for the Mets after this season isn’t clear. A McDonald’s outpost at Citi Field is not something that has been discussed at this point, Mallette said. Goldberg pointed out that Shake Shack already has a presence at the park. (“There’s no issue with the two of them, by the way, they’ve been supportive of it, so that’s been cool,” Goldberg said of Shake Shack.)

One way or another, Mets fans have probably given both companies their money’s worth.

“One way to look at the dollar value of that partnership is to look at the media exposure that both brands get,” Leland said. “They’re getting your media exposure for free, right? This article you’re going to write is media exposure for them. They did not pay for it, so that’s advertising money neither one had to pay.”

(Top illustration by Dan Goldfarb / The Athletic; Photos: Marcus Ingram / Getty Images)