A study of ancient walrus DNA reveals Viking trade routes in Greenland, highlighting Norse interactions with Indigenous Arctic peoples before Columbus’s time.

By analyzing ancient walrus DNA, an international research team led by Lund University in Sweden has retraced the walrus ivory trade routes of the Viking Age. Their research, recently published in Science Advances, indicates that Norse Vikings and Arctic Indigenous peoples met and traded ivory in remote parts of High Arctic Greenland, several centuries before Christopher Columbus “discovered” North America.

A Driving Force Behind Norse Expansion

In Medieval Europe, there was an enormous demand for elite products, including walrus ivory. The Vikings played a vital part in the ivory trade, driving the Norse expansion into the North Atlantic to Iceland and then Greenland as they looked for new sources of ivory

“What really surprised us was that much of the walrus ivory exported back to Europe was originating in very remote hunting grounds located deep into the High Arctic. Previously, it has always been assumed that the Norse simply hunted walrus close to their main settlements in southwest Greenland,” says Peter Jordan, Professor of Archaeology at Lund University.

Advanced Genetic Techniques Reveal Source of Ivory

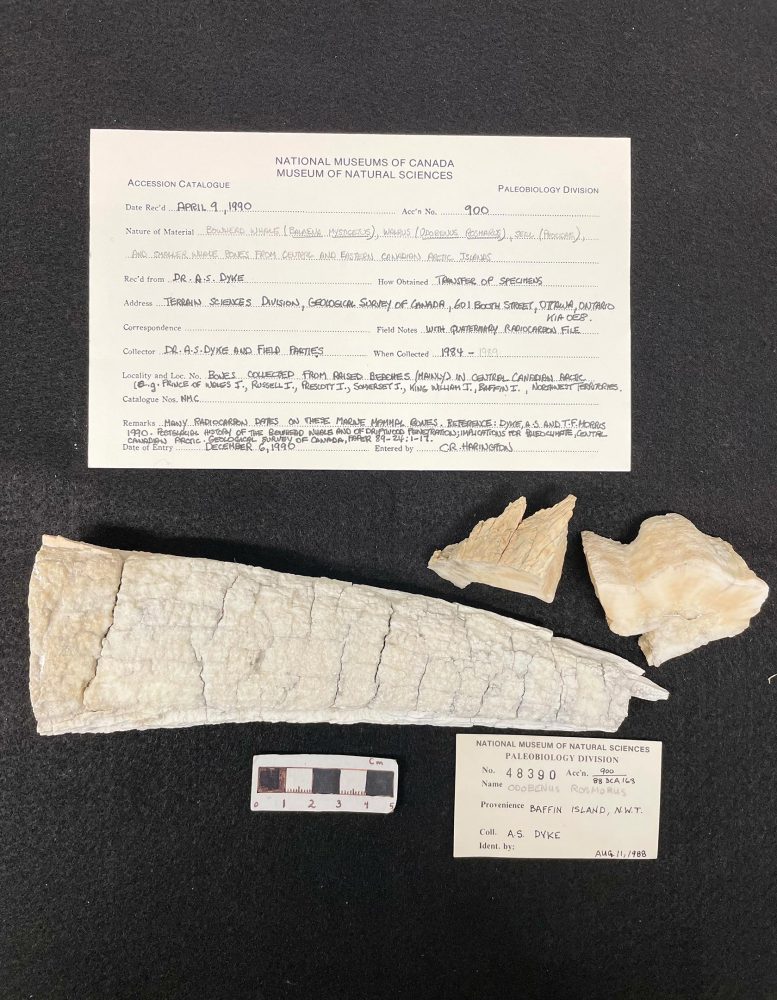

The researchers used genetic “fingerprinting” to reconstruct precisely where traded walrus artifacts were coming from.

“We extracted ancient DNA from walrus samples recovered from a wide range of locations across the North Atlantic Arctic. With this information in place, we could then match the genetic profiles of walrus artefacts traded by Greenland Norse into Europe back to very specific Arctic hunting grounds,” explains Dr. Morten Tange Olsen, Associate Professor the Globe Institute in Copenhagen.

Experimental Voyages Shed Light on Norse Seafaring Capabilities

As the new results started to emerge, another key question arose: if ivory was being obtained from the High Arctic, did the Greenland Norse have the seafaring skills and technologies to venture so deep into ice-filled Arctic waters?

Research team member Greer Jarrett sought answers to this question in a unique way: he reconstructed probable sailing routes, taking experimental voyages in traditional clinker-built Norwegian boats.

“Walrus hunters probably departed from the Norse settlements as soon as the sea ice retreated. Those aiming for the far north had a very tight seasonal window within which to travel up the coast, hunt walrus, process and store the hides and ivory onboard their vessels, and return home before the seas froze again,” says Greer Jarrett, a doctoral researcher at Lund University.

Cultural Encounters in the High Arctic

After the Norse completed their perilous journeys, what might they have encountered? Importantly, these remote High Arctic hunting grounds were no empty polar wilderness. They would have been inhabited by the Thule Inuit and possibly other Indigenous Arctic peoples, who were also hunting walrus and other sea mammals. The new research provides further independent evidence for the long-debated existence of very early encounters between the European Norse and North American Indigenous peoples, it also confirms that the North Water Polynya was an important arena for these inter-cultural meetings.

Contrasting Norse and Indigenous Arctic Lifestyles

“This would have been the meeting of two entirely different cultural worlds. The Greenland Norse had European facial features, were probably bearded, dressed in woolen clothes, and were sailing in plank-built vessels; they harvested walrus at haul-out sites with iron-tipped lances,” says Jordan.

In contrast, the Thule Inuit were Arctic-adapted specialists and used sophisticated toggling harpoons that enabled them to hunt walrus in open waters. They would have been wearing warm and insulated fur clothing and would have had more Asian facial features; they paddled kayaks and used open umiak boats, all made from animal skins stretched over frames.

“Of course, we will never know precisely, but on a more human level these remarkable encounters, framed within the vast and intimidating landscapes of the High Arctic, would probably have involved a degree of curiosity, fascination, and excitement, all encouraging social interaction, sharing, and possibly exchange. We need to do much more work to properly understand these interactions and motivations, especially from an Indigenous as well as more “Eurocentric” Norse perspective,” concludes Jordan.

Reference: “Greenland Norse walrus exploitation deep into the Arctic” by Emily J. Ruiz-Puerta, Greer Jarrett, Morgan L. McCarthy, Shyong En Pan, Xénia Keighley, Magie Aiken, Giulia Zampirolo, Maarten J. J. E. Loonen, Anne Birgitte Gotfredsen, Lesley R. Howse, Paul Szpak, Snæbjörn Pálsson, Scott Rufolo, Hilmar J. Malmquist, Sean P. A. Desjardins, Morten Tange Olsen and Peter D. Jordan, 27 September 2024, Science Advances.

DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adq4127