Following the pandemic tech boom, edtech company Byju’s was India’s most valuable start-up in 2022, worth an estimated $22bn.

The company, founded by a charismatic former maths teacher Byju Raveendran, sold tutoring services to millions of parents seeking to prepare their children for India’s brutally competitive school entrance exams.

After winning investment from the likes of Mark Zuckerberg, BlackRock and Dutch tech investor Prosus, Byju’s went on a global acquisition spree and became a sponsor of the Fifa World Cup in Qatar and the country’s cricket team.

But after central banks raised interest rates following the Covid-19 pandemic, the cheap money dried up. The value of the company plunged, and investors were forced to write off stakes worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Creditors of Byju’s are now in US courts to locate almost half of a $1.2bn loan, while the company fights insolvency proceedings in India over delayed national cricket authority sponsorship dues. The Qatar Investment Authority has also launched a case in India’s tech hub of Bengaluru, where Byju’s is based, to recover more than $200mn from Raveendran.

Byju’s has been unable to access its bank accounts and pay salaries as a result of the Indian legal proceedings, Raveendran said in a company-wide email in August shared with the Financial Times. “I have felt like a man screaming into a hurricane of hurdles,” Raveendran said. “When we regain control, your salaries will be paid promptly, even if that means raising more personal debt.”

Byju’s, which is now worth $120mn according to data provider Tracxn, has denied wrongdoing. Raveendran told the FT that his company no longer had access to capital and the entirety of the $1.2bn term loan at the heart of the sprawling legal battle with its creditors had been spent.

He said they had not been able to pay their lawyers in a Delaware court case and that what he described as the company’s “strategy” of trying to conceal money from creditors “has not gone right”. Raveendran added: “I will fight it out because we will win eventually.”

The company’s legal battles from Delaware to Bengaluru have shone a harsh light on start-up corporate governance standards, said Shriram Subramanian, founder of Bengaluru-based proxy advisor InGovern Research Services. “It’s a big failure of corporate governance from multiple perspectives,” he said.

Byju’s overdue accounts released in January showed losses almost doubling to nearly $1bn in the year to March 2022. While the platform still has about 7mn paying users, the number of employees — more than half of them teachers — has plunged from about 80,000 at its peak to about 27,000 today, Raveendran said.

Subramanian questioned why investors tolerated Byju’s delayed filing of accounts and pointed out that the company did not have a chief financial officer for 16 months between 2021 and 2023.

“The Byju’s saga has a general resonance,” Subramanian added. “There is an element of caution and more scrutiny of start-ups, investors are expecting more due diligence and a path to profitability. No more is there a blind throwing of money.”

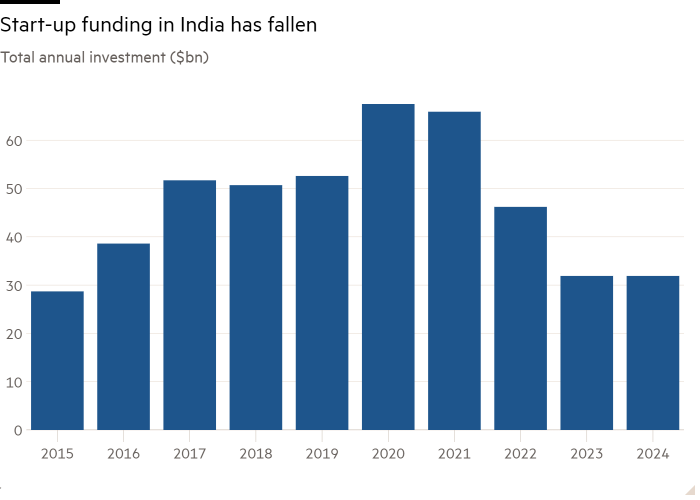

Total annual funding to Indian start-ups was $32bn last year, less than half of the 2020 peak of $67.3bn, according to Tracxn.

“The different layers of scandal that have draped this company for the last couple of years create a very complex cocktail of issues,” said Nirgunan Tiruchelvam, a Singapore-based analyst at Aletheia Capital. “It’s not good for the tech ecosystem in India.”

A lawsuit launched in Delaware by a group of more than 100 creditors to recover $533mn of the $1.2bn syndicated loan to Byju’s secured in November 2021 has revealed disorganisation at the edtech company.

Earlier this year, Raveendran’s brother Riju struggled to explain to a US judge that he did not know the whereabouts of $533mn of the loan. Riju, who was the sole director of US-based Byju’s Alpha, a company created to receive loans, said in May: “I really don’t know where the money is.”

Riju, who lives with Raveendran and his wife Divya Gokulnath, the company’s husband-and-wife co-founders, in Dubai’s affluent Emirates Hills community, said he had sent emails asking them where the money was.

Raveendran said Riju had not lied as he had restricted information to him.

Riju’s attempts to find the funds “were tepid at best” and his “testimony lacks all credibility”, said US bankruptcy judge John Dorsey at the May hearing. The court found him in contempt and in July imposed a fine of $10,000 a day until the money was located.

“I have struggled in my own mind whether we are seeing ineptitude . . . or we’re seeing something more nefarious,” said Ravi Shankar, a Kirkland & Ellis advocate acting for Glas Trust, an agency representing more than 100 Byju’s creditors. “Two brothers doing whatever it can take to salvage a crumbling empire.”

After Byju’s Alpha was accused by the creditors of default, they removed Riju as sole director of the company in 2023 and installed Timothy Pohl, a restructuring expert. Last month, Delaware’s Supreme Court affirmed that default.

Pohl unearthed bank accounts that showed transfers signed off by Riju to a little-known Florida-based hedge fund Camshaft Capital. It was set up in 2020 and registered with the address of an IHOP pancake restaurant in Miami by then-23-year-old William Morton, a high school dropout with no investment qualifications.

In a separate Florida suit, the creditors’ lawyers allege Morton splurged on Ferrari, Lamborghini and Rolls-Royce cars after the Byju’s transfer, as well as a condo with an ocean view with a listed monthly rent of $29,000.

Morton’s lawyers said Camshaft “vigorously denies” the allegations. In June, they told the Delaware court that millions of dollars in fees he received in the deal were “not with us today”.

Earlier this year, it emerged in court that Camshaft transferred the funds to OCI, a British company. The creditors’ lawyers are now seeking documents about the transfer in UK courts. Morton and OCI did not respond to a request for comment. Raveendran said Camshaft had not lost the company money and declined to comment on OCI.

Riju’s lawyers at the end of July said in court that funds were spent on goods and services for Byju’s and “not for an improper purpose”. Byju’s has launched a counter-lawsuit in New York against the lenders, accusing them of unfairly accelerating the loan terms and negotiating in “bad faith”.

Raveendran added “there has never been any fraud” and “not a single dollar” of the loan was transferred to India or personal accounts.

Byju’s faces more legal challenges in India. The Qatar Investment Authority — the country’s sovereign wealth fund, which invested in the company and loaned Raveendran $250mn in 2022 — is fighting in a Karnataka court to claim back more than $200mn from him. Raveendran declined to comment on the QIA case.

Byju’s was also pushed into bankruptcy proceedings in India by the country’s national cricket authority over unpaid sponsorship dues. Although the company settled the case in August, India’s Supreme Court stayed the settlement order after the US creditors alleged Byju’s might have used money from their loan to pay the Board of Control for Cricket in India. Byju’s has denied the allegation.

The lenders know that time is not on their side. Earlier this year, they said the cost of recovering the funds could make “finding the money nothing more than a Pyrrhic victory”.

Raveendran said Byju’s would pay back the lenders. “If they have the patience, come work with me,” he said. “We will make a comeback.”