A resident physician says Manitoba’s doctors-in-training are being charmed by other provinces offering incentive packages specifically for physicians beginning their careers.

While Manitoba offers various incentives for physicians throughout their years of practising, the province doesn’t present those starting their careers with what’s called a return of service agreement — a financial incentive for medical students and residents who agree to work in certain locations for a period of time.

A number of other provinces, including Saskatchewan and Ontario, offer these contracts, but Manitoba doesn’t.

Dr. Stefon Irvine, who is in the first year of a medical residency that will take him to northern Manitoba, is worried the province is losing future physicians because it doesn’t have these incentives.

The province last provided a return of service agreement for Canadian residents in 2017.

“Maybe it wasn’t our silver bullet and our only answer, but it was certainly helping,” said Irvine, who is Cree and Métis and wants to practise in northern Manitoba, where he grew up.

A report last year from the Canadian Institute for Health Information found Manitoba has 215 doctors per 100,000 residents — the second-lowest rate in the country and well below the national average of 247.

This summer, Irvine took it upon himself to conduct an informal survey of medical students and family medicine residents in Manitoba. Within 10 days, he found more than 30 people actively seeking or negotiating return of service agreements with other provinces.

He shared the list of names with the provincial government, as part of a letter he wrote asking for return of service agreements to be offered again. The answer to his request was a “quick no,” which came as a disappointment, he said.

“We keep hearing about these 400 doctors they want to hire over so many years,” Irvine said of an NDP commitment.

He says it felt like he and other residents and medical students “were handing them so many of those doctors who are ready and willing to stay in Manitoba.”

But for doctors starting their practice, “with the financial realities they’re facing, they’re at that point where they’re starting to look at other provinces.”

“I already know three of the people on the list that are no longer up for grabs in Manitoba, that they’ve fully signed and committed to other provinces.”

‘Mixed experience’ with past agreement: province

The letter to Irvine, written by deputy health minister Scott Sinclair, states Manitoba had “mixed experience with the effectiveness” of the previous return of service agreement.

His letter pointed to efforts to bolster recruitment and retention in Manitoba, including the new physician funding model implemented last year, which the advocacy group Doctors Manitoba said would provide a “significant increase” in funding.

Sinclair also pointed to what he said is an improved physician retention program and the creation of a rural and northern retention program.

Irvine applauded those efforts, but said they don’t help residents and medical students who are carrying hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt, and struggle financially in the years before they start practising.

In his case, the monthly payment on his loans, coupled with bills and other expenses, exceeds his pay, he said.

Those financial pressures make return of service contracts attractive to residents and medical students, said Irvine.

“I want resident physicians to be able to live month-to-month and not worry about how they’re going to balance their book … and a return to service incentive is that answer.”

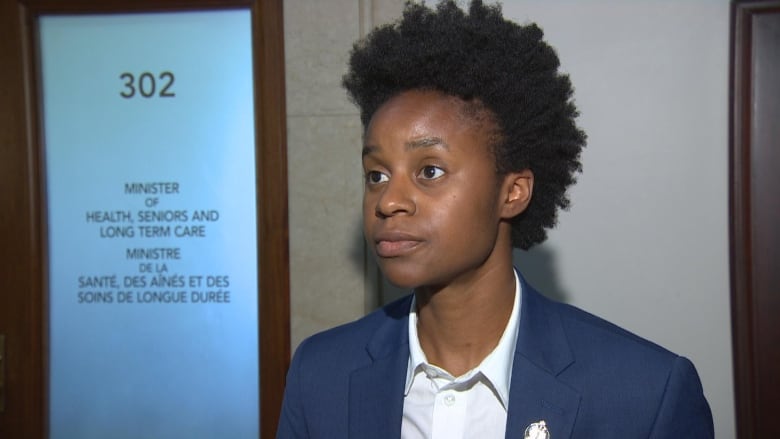

Health Minister Uzoma Asagwara said they appreciate the financial challenges of physicians-in-training, citing scholarships, bursaries and mentorship opportunities from post-secondary institutions as some of the available supports.

Asagwara said the government provides assistance throughout a physician’s career, financial and otherwise.

“I’ve heard from many students that it’s not necessarily just about the dollars and cents,” they said.

“It’s really about that connection you can make on-site, in communities, to ensure that, for example, your family is able to access child care, that your kids can go to a good school, that you can be mentored by physicians and peers where it is that you’re practising.”

Better solutions needed to stop ‘revolving doors’: doctor

Dr. Jose Francois, the chief medical officer for the provincial agency Shared Health, said Manitoba’s use of return of service agreements has fluctuated over the years, and has primarily focused on rural and northern areas.

“Unfortunately, many people did not stay beyond their contract or, on some occasions, bought out their contract,” he said in a statement, saying the agreements “were not an effective long-term recruitment solution.”

The focus now is on training in rural and northern Manitoba to improve the recruitment and retention of resident physicians, he said.

Shared Health currently offers return of service agreements to certain individuals, such as international medical graduates who hope to work in Manitoba and internationally trained students entering the University of Manitoba residency program.

Some communities may choose to enter into return of service agreements, but nothing is formalized on a provincewide basis.

Dr. Amanda Condon has recruited physicians to work with her in rural Manitoba for years.

She isn’t convinced of the effectiveness of upfront financial packages, she said.

An incentive “maybe gets somebody in the door … and some might argue that that’s what we need right now,” Condon said.

“However, I think the other side of it is what … we need to do to have people in communities and in places longer, so we don’t have revolving doors of providers.”

Irvine said he’s certain incentives would help Manitoba, citing a report from Atlantic Canada that listed financial incentives as one of the predictors of physicians thriving in rural communities.

He knows he’ll eventually be paid well as a physician, but said for now, he and his colleagues want some help getting by, especially when neighbouring provinces are dangling money in front of them.

“I would urge the current government to relook at not only the previous [provincial] program, and what worked and didn’t work about it, but also to look across Canada,” he said.

“Certainly there’s other provinces that are doing a better job at recruiting and retaining both staff physicians and resident physicians.”