This article is an on-site version of our Chris Giles on Central Banks newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Tuesday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Hello, I’m Joel Suss — data journalist at the Financial Times and stand-in for Chris Giles while he takes a much deserved break.

With the recent jumbo Fed pivot, an easing cycle is officially under way across most major western economies. But while the direction of travel is clear, the pace and destination are still highly uncertain.

I’m going to explore competing arguments for a faster or slower pace across a number of central banks and give a steer as to which is most convincing. Let me know if you agree with my analysis — or share yours with me — in the comments below.

Gradualism under fire in the Eurozone

After a second quarter-point cut on September 12, ECB policymakers were quick to declare another reduction in October unlikely. Influential member Philip Lane summed up the prevailing ECB stance as “a gradual approach to dialling back restrictiveness . . . if the incoming data are in line with the baseline projection”.

But downbeat economic data last week and a larger drop in inflation than expected are testing ECB gradualism and raising market expectations of another cut in October.

At the start of last week, Eurozone PMI surveys showed a sharp and unexpected drop in activity. This was broad-based, with France’s fall into contractionary territory the lowlight. This survey should not be dismissed as simply bad vibes: recent ECB analysis finds a tight correlation between PMIs and subsequent real GDP growth.

Then, on Friday, inflation figures from France and Spain surprised sharply to the downside. The flash estimate of Eurozone inflation released this morning corroborates a larger-than-expected drop in the headline rate — to 1.8 per cent — in September.

At the start of last week, market prices implied a less than 30 per cent chance of a cut in October. By the end of the week, that had risen to more than 80 per cent. ECB president Christine Lagarde, in testimony to the European parliament on Monday, gave the idea of an October cut more credence, saying “the latest developments strengthen our confidence that inflation will return to target in a timely manner”.

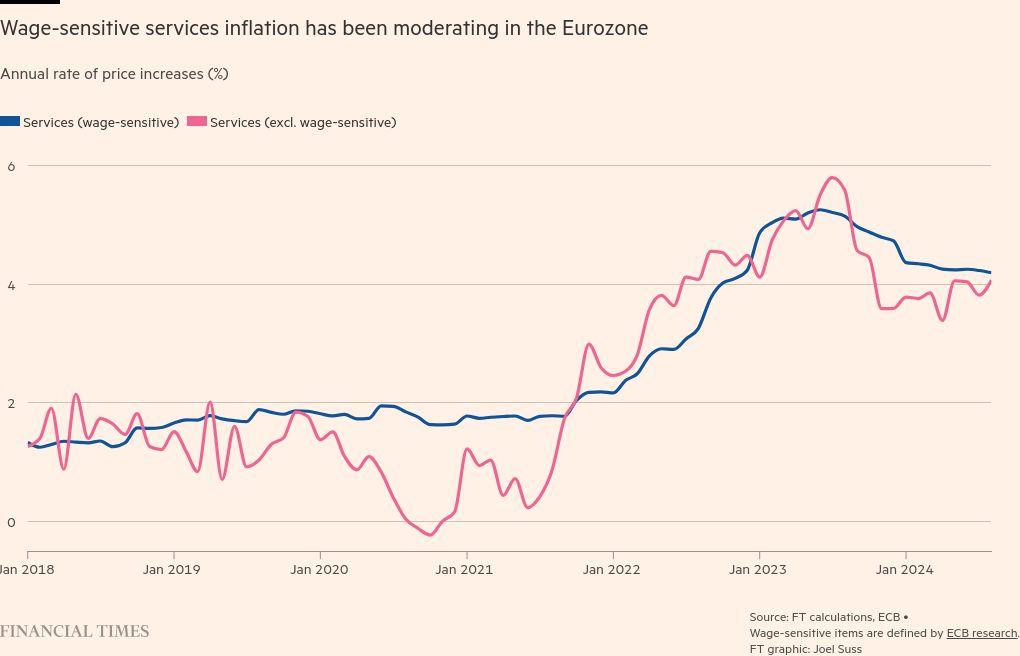

What about the argument for a slower pace of cuts? Hawkish members of the ECB point to stubborn wage increases feeding through to services prices. But a careful look at the data reveals a less worrisome picture.

Below I decompose services inflation into items which are wage-sensitive versus those that are not (based on the ECB’s own designation). As you can see, recent increases in services inflation in the Eurozone are due primarily to items that are not wage-sensitive. This amounts to a green light for a faster pace of rate cuts in the Eurozone.

Time to declare victory at the Fed?

Federal Reserve chair Jay Powell was masterful in communicating the central bank’s half-point move in September. It was a cut of confidence. “The US economy is in good shape . . . inflation is coming down, the labour market is in a strong place, we want to keep it there,” Powell said. Concerns that a larger than normal cut would spook markets were unfounded.

Powell did concede that labour market cooling was concerning Fed rate-setters. But he emphasised that the Fed’s confidence in inflation returning sustainably to target enabled the move.

Not everyone agrees inflation has been vanquished, however. Michelle Bowman was the first Fed Governor in nearly two decades to dissent, arguing for a slower pace of easing. “Bringing the policy rate down too quickly carries the risk of unleashing that pent-up demand,” she said, pointing to prominent “upside risks to inflation”.

A rebound in inflation could happen, and faster than most people appreciate. Recent research using detailed bank transaction data suggests monetary policy shocks have sizeable immediate effects, in contrast to the received wisdom that policy operates only through “long and variable lags”. Alberto Musalem, of the St Louis Fed, echoed this argument in an interview with the FT, saying that the US economy could react “very vigorously” to looser financial conditions.

The Fed appears split on the pace necessary. So does the market — futures prices yesterday indicated a roughly 60 per cent probability of another quarter-point cut versus 40 per cent for a second half-point cut in November. August inflation figures, released on Friday, did not tip the argument in either direction, with the headline rate a bit lower than expected at 2.2 per cent but core inflation (excluding food and energy) at 2.7 per cent.

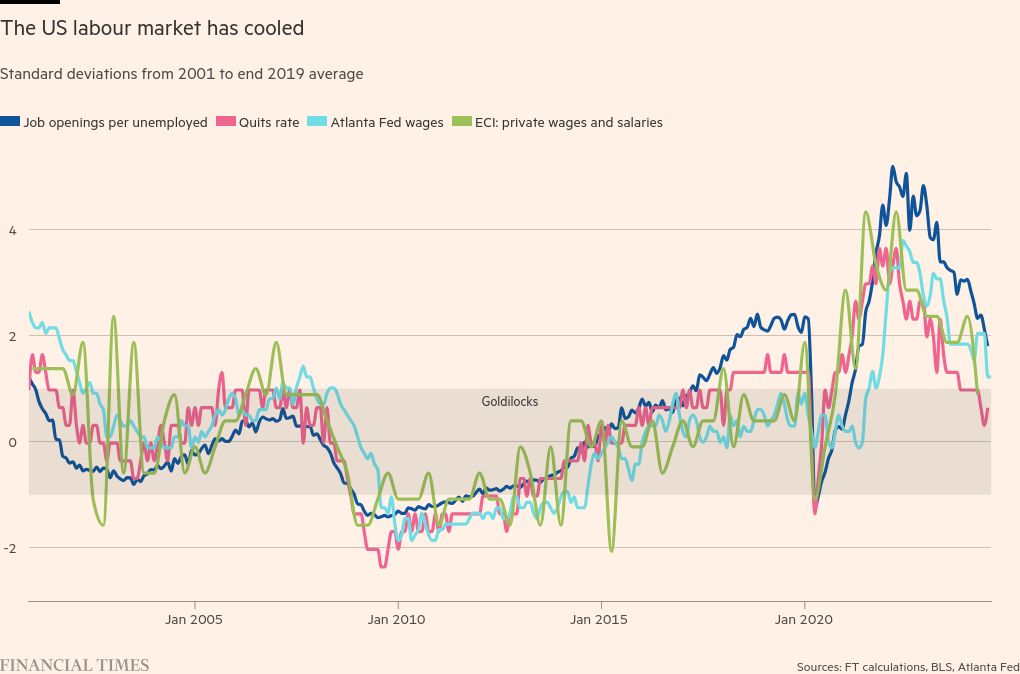

Powell’s characterisation of a strong but cooling labour market conforms to the data. Below I’ve plotted where some key data points are in relation to their 2001 to 2019 average values. All are above, and mostly more than one standard deviation above the mean.

Economic growth has been remarkably strong in the US over the past several quarters, and following revisions to GDP estimates on Friday it is even stronger than originally thought. From 2021 to 2023, real GDP was revised upwards by a cumulative 1.2 per cent.

This suggests to me that a slower pace of easing is justified. The market is expecting at least 0.75 percentage points of additional cuts by year end. This is more than I think is likely to be delivered in the context of rude economic strength and a strong labour market. Powell’s speech yesterday confirmed that his baseline is two quarter-point cuts.

But there is a lot of upcoming data to digest ahead of the Fed’s next meeting on November 7, starting with September payrolls and unemployment figures this Friday.

Bank of England

The Bank of England, like the ECB, has been taking a “gradual approach” to reducing rates.

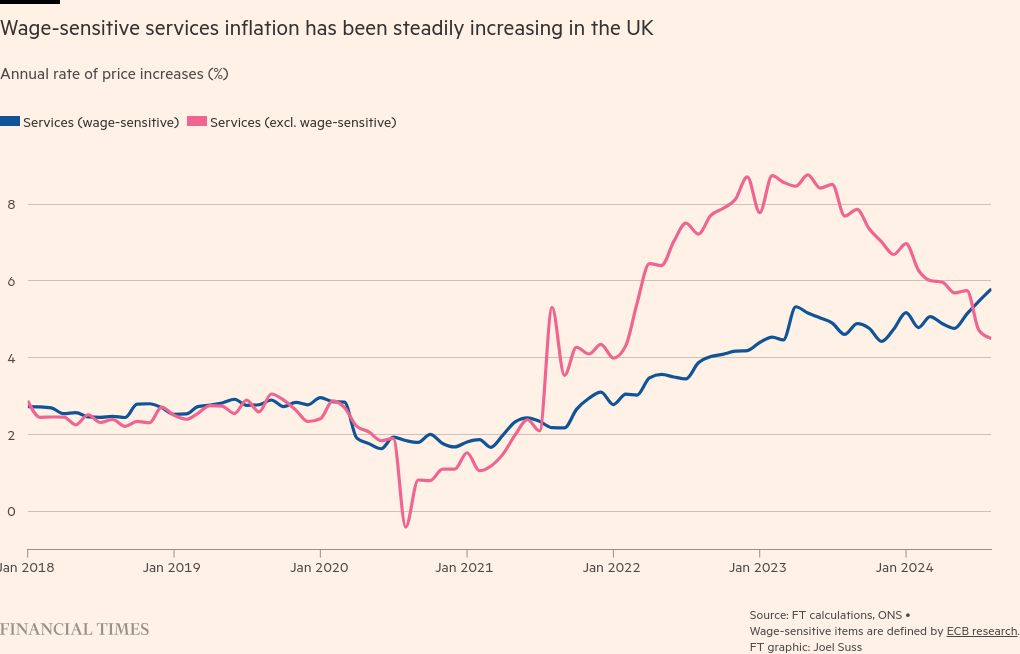

After a first cut in August, the Monetary Policy Committee decided to stand pat in September. Hawks on the committee, led by externals Catherine Mann and Megan Greene, are primarily concerned about a wage-price spiral.

As with Eurozone services inflation above, I’ve decomposed CPI services into wage-sensitive and non-wage-sensitive components. But the resulting picture for the UK looks very different to that of the Eurozone — wage-sensitive services inflation has been steadily increasing over time, whereas wage-insensitive services inflation has been decreasing.

The hawks on the MPC have more to be concerned about on this front, and the BoE is therefore justified in moving more slowly.

Bank of Japan

Most central banks are ruminating about easing rates, but for the Bank of Japan the situation is reversed.

Rather than wanting to see evidence of a dissipating wage-price spiral, the BoJ is eager for signs that the “virtuous” spiral is taking hold.

Despite severe market turbulence following the BoJ’s 0.15 percentage point rise in July, governor Kazuo Ueda last week reiterated the central bank’s confidence that it can continue to normalise policy, although he hinted that the pace would be gradual. The BoJ had “enough time”, Ueda said, to survey economic developments in Japan and abroad.

The surprise ascension of Shigeru Ishiba as LDP leader and Japan’s next prime minister over Sanae Takaichi removes potential political pressure on the BoJ to reverse course. Takaichi had advocated for easy monetary policy, while Ishiba is supportive of the BoJ normalising rates.

But the BoJ is right to proceed cautiously. It wants to be sure that inflation is going to remain sustainably at target, and policy remains easy even after the recent rise.

What I’ve been reading and watching

A chart that matters

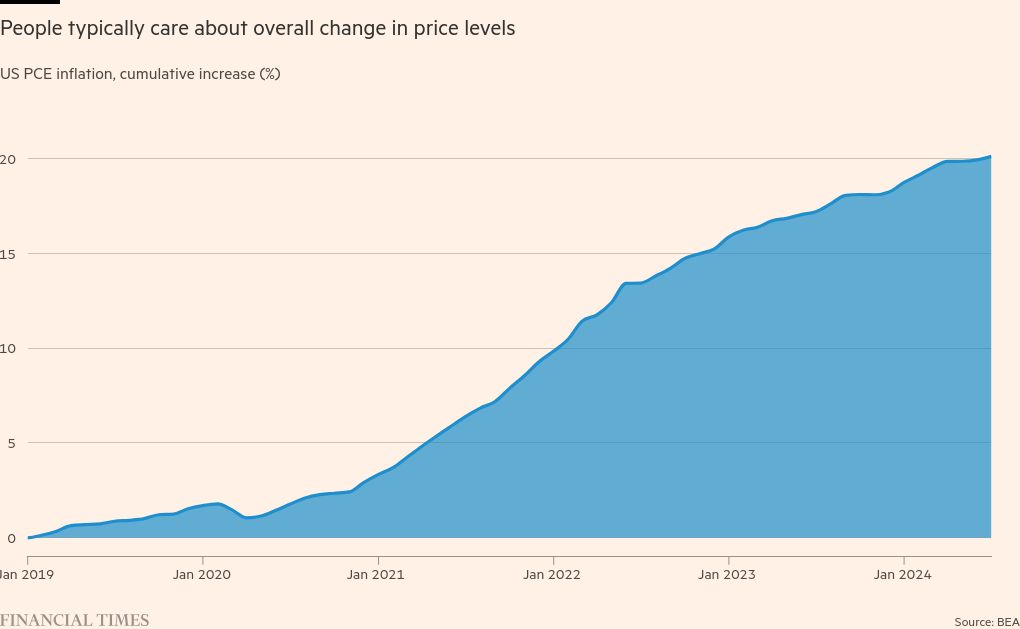

When steeped in central banking communications it is easy to lose sight of how inflation is perceived by the general public.

Central banks focus on their inflation mandate — typically aiming to have the annual rate of overall inflation hit 2 per cent. But people judge inflation in terms of levels rather than rates.

Or as Jared Bernstein, chair of the White House council of economic advisers, put it: “Economists obsess over rates; regular people obsess over levels.”

With inflation nearing 2 per cent, policymakers and politicians have cause to celebrate. But they would also do well to remember that regular people probably won’t be celebrating. In the US, prices are on average 20 per cent higher than they were in 2019, as the chart below shows.

Recommended newsletters for you

Free lunch — Your guide to the global economic policy debate. Sign up here

Trade Secrets — A must-read on the changing face of international trade and globalisation. Sign up here