Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Workplace pensions myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Every five years, Japan’s Government Pension Investment Fund sends a frisson of excitement through the investment community. This is one such year: when the country’s largest fund conducts a quinquennial review of its investment assumptions — encompassing everything from inflation to expected returns for various asset classes.

These decisions determine the ¥246tn ($1.6tn) fund’s policy portfolio and how much money goes to which asset classes. It may also have an impact on how much will go to each of its 39 outside fund managers and whether that list may expand.

Established in 2006, GPIF was set up to manage part of Japan’s national public pension and its reserves, and to create enough investment growth to meet the needs of the country’s rapidly ageing population. Since 2014, the fund has held roughly half its assets in equities and half in fixed income instruments, both split between domestic and overseas holdings.

However, the notion that most of us can retire from work as we enter our mid-60s is becoming outdated. As an example, Japan has the largest proportion of workers over the age of 65: at 13.6 per cent, according to OECD data.

This group may want to keep busy, or perhaps needs the added income to forestall years of living off savings and any pension income. The country needs these workers, too. Japan’s overall population is just over 124mn people, but falling: the country lost an annual average of about 550,000 citizens between 2021 and 2023, according to data from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. That meant that, in the year to October 2023, the working population fell by 256,000.

Japan’s retirement system is thus vital. It comprises a flat-rate basic pension, an earnings-based employee pension, and voluntary private pension plans. The first two are both defined-benefit plans and the last one is defined contribution. The first, and largest, provides a basic income to all Japanese citizens, employed or not.

“Combining these factors reveals an estimated breakdown of 48 per cent [of retiree income] from the national pension, 33 per cent from the employee pension, and 19 per cent from the corporate pension,” explains Katsutoshi Inadome, senior strategist at Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Asset Management, one of the largest asset managers in Asia.

During 1999-2000, Japan undertook very contentious reforms to these pensions systems, designed to prepare the country for the result of a rapidly ageing population and a low fertility rate of just 1.2 children per woman. Basic pension benefits were reduced, and retirement ages for men were lifted from 60 to 65. An effort was made to fund the national pension’s reserves — the GPIF — using riskier assets, mostly equities.

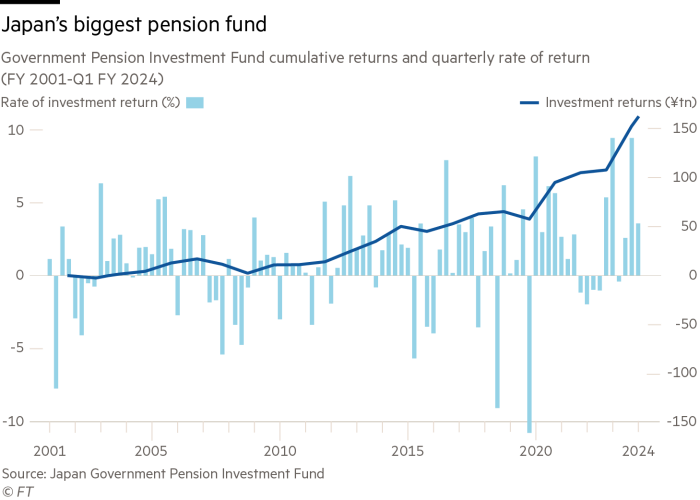

That has helped. Investment performance at GPIF in calendar year 2023 was up 22.7 per cent, its second best year ever. Partly, that improvement stems from a weakening yen as well as GPIF’s shift to outside managers who use active strategies. As of the end of 2023, the fund had ¥17tn ($121bn) with this group and the rest with passive managers. There could be even more shifts towards active management over time.

Indeed, alternative asset managers — those investing in assets including infrastructure, private equity and real estate — hope that GPIF eventually increases its weighting in this area. In March 2024, it was just under 1.5 per cent. Any increase depends on the path of interest rates worldwide. “We believe that high interest rates may reduce the benefits of leverage in alternative asset investments,” says to GPIF chief investment officer Eiji Ueda.

However, in spite of the reforms, Japan’s system does not score highly when compared with its global peers. An annual ranking of 47 country’s systems by pension consultants Mercer, along with the CFA Institute, gave Japan a score of 56.3 out of 100. That’s enough for only a C grade — in line with Italy, China, and South Korea.

The sustainability of Japan’s pension system worries David Knox at Mercer, the report’s author. Can the existing pension systems continue to deliver, notwithstanding the demographic and financial challenges, asks the report.

Its basic pension for the aged “only meets about 18 per cent of the national average wage,” points out Knox. “Better systems pay at least 25 per cent and, in some cases, over 30 per cent in the OECD. Australia’s pas is at 28 per cent and Denmark at 36 per cent.”

Japan’s pension system therefore faces a daunting task, even after its reforms. Changing the GPIF’s investment policies to take on more risk, has been lauded. “Yet it’s not about the investment but about the overall reform,” says Akiko Nomura at the Nomura Capital Markets Institute. “We should look at the overall system rather than just the investment side.”