Known as tahriib, they are clandestine travellers seeking to escape conflict, poverty and the effects of climate change. Over the past decade, their journeys across the Gulf of Aden have become increasingly chaotic, a microcosm of the forces driving worldwide flows of human traffic.

Between the Indian Ocean and the Red Sea, this stretch of water separates the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. No other place on earth has witnessed more cycles of conflict, forcing so many people into successive rotations in such a small space. Today, contraflows of migrants and refugees move through a labyrinth of ever-more-dangerous routes, exchanging insecurities, jumping between continents, from one battlefield to another. They criss-cross Ethiopia, Somalia, Djibouti, Yemen and Saudi Arabia, a human shuffle in which the odds are never favourable.

A generation of young men and women has been seduced by a growing network of middlemen, promising jobs and a better future elsewhere. Promises that have, in turn, fuelled a new model of people trafficking, drawing the tahriib into a world in which there is often complete disregard for life.

The cracking sound jarred Sami from his sleep. A floundering came from the ladder that led up to the overhanging sleeping quarters. The broken top rung must have given way again. Probably a visitor. A new farm boy from the plains or another tahriib seeking shelter.

Sami lay there, his head under a flapping, shiny curtain at the open window that could not be pulled back. Listening to the rhythm of his own breath, he could make out the sound of a car turning into the potholed street, making its way through the last of the deep puddles left by the rains. Downstairs, the sound of running water came from a hose in the tiled courtyard, someone taking a shower.

There was shouting. Tongues that could not be understood. Semi-awake, Sami turned gradually on the lean foam mattress, sensing that it must be afternoon and that he was the only one in the small, sulphur-yellow room. The others must have been out, hustling for work or else on the hunt for cheap snacks sold by women with pans of hot oil in the alleyways around Place Rimbaud.

Sami’s mind was rattling, thoughts lurching between memories of his home in Dire Dawa, Ethiopia, and the streets of Djiboutiville, capital of Djibouti, where he now found himself in limbo. He imagined the well-trodden paths of Quartier Quatre nearby: the alleyway where weightlifters trained; the tin mosque with a green door, standing at such a slant that it was propped up with sand bags; the blue phone cabin next to three pink houses; and the spot on Avenue Thirteen where the girl had smiled at him last night.

Sami recalled a conversation five years ago, sat gathered on a patch of cool earth under a damas tree with his best friend, Araso, and some other boys who worked on the farms. He was 15 then, and his mother had recently died. Sami was numb. Nearly all of the boys in the villages around Dire Dawa had been visited by the dilals, local brokers who spun tales of riches and wonder abroad. Like campfire fable-tellers, they spoke reverently of a quixotic figure who would guide and watch over them. That was when he first heard the name of Abdul Qawi.

Around the Gulf of Aden, thousands are searching for Abdul Qawi. Unlike the dilals, who are merely middlemen, Abdul Qawi is in many tellings a legendary people smuggler operating in this region. In others he is a powerful warlord to be avoided. Some chatter loudly, questioning whether he is real or not, alive or dead, good or evil. Some tout theories, deeming him to have been shot, or to have escaped, disappeared, in this place or that. Whether he is fact or fiction is inconsequential. His name no doubt continues to lure thousands to their deaths.

The stories did not need to be true to be believed. “So many young boys in my area were travelling to Yemen or Saudi for a better life,” Sami said. “We tracked down a dilal and went to his house to work it all out. My cousin stayed on to look after my family’s small house and I set off with five friends.”

The journey included a 250-kilometre walk around Djibouti’s coastline to Obock, through a vast lava field of sharp, black rocks. Depressed below sea level, the earth is encrusted with a thick layer of salt made whiter still by the glaring sun. Avoiding checkpoints on the roads, gravel patches make for the best going underfoot. Spread out along the well-worn route, blue barrels sit like way-markers. A lifeline from which to drink, they have been left for the hundreds of parched migrants and refugees who walk by each day.

Their internal voices full of stories and possibilities, Sami and his friends pressed on undeterred. He took a boat from near Obock with 70 others. “We were dropped into the water near a beach where there was a group of 10 men with Kalashnikovs waiting. It was the first time in my life I was really, really scared. We were all taken in a big truck to a camp.” There were seven women with them and, when they reached the hosh, or camp, the group was split up. “There were lots of other migrants there, around 400 in total, from Somalia and Sudan but mostly from Ethiopia.”

In the smuggler’s encampments near Res al-Ara, on the southwestern tip of Yemen, the first questions they were asked were whether they knew anybody in Saudi Arabia, England or the US. “If you then tell them you have relatives, you are forced to hand over the contact number of somebody you know there. Then they immediately start asking for $3,000. If you don’t know anybody, then they start hitting you.” Sami said beatings, torture and rape were commonplace. “If they want ransom money, then they immediately start making videos of you suffering. For the women it’s worse. Every tahriib in there is crying but even though your eyes become tired, even at midnight you don’t sleep.

“In the camp, they don’t want to kill you, but the gangs there are very violent. They take the same drug, called Dama, that fighters take. It closes your heart.” The synthetic drug Captagon, sometimes called Dama in Yemen, has become common on battlefields, allowing users to stay awake for days and feel invincible.

Sami does not sleep much these days. Easing himself up slowly from the mattress in the yellow room, he drew his mouth down in pain. From beneath a tightly fitting T-shirt, a lumpy channel of white scar tissue extended the length of his abdomen. A discomfort, a constant reminder. Fifteen days into his captivity, a deranged guard had stormed into the compound. Wild-eyed, he flung himself from wall to wall before stabbing Sami in the stomach.

Irrational violence is commonplace within Yemen’s smuggling mafia, but most is premeditated and methodical. Prescribed by ringleaders, it is enacted by compliant henchmen as a means of extortion. The past decade has seen wholesale trafficking and hostage-taking evolve into a multimillion-dollar business.

Bleeding and unconscious, Sami was left for dead, dumped by his captors on a road. A passing vehicle took him to hospital. After his recovery, he travelled to Sana’a and spent a long time trying to claim asylum, find work and build a new life for himself. Sami was sleeping on the streets of Sana’a when fighting broke out. “Bomb craters, missiles falling and every 20 minutes or so there were more soldiers on the road.”

Several days after leaving the capital on foot, Sami reached a Houthi checkpoint, along with five others including his best friend, Araso. “We explained that we were just refugees and were trying to make our way to Saudi. They told us to come with them or they would kill us. We were scared, of course, and when we tried to plead with them, they shot Araso directly in the face. Only then we followed.”

The Houthi fighters demanded they work for them, carting supplies and munitions into the mountains. “In between, they would teach us how to fight. To fire a weapon and to throw bombs. My consciousness was telling me not to fight, that I had to save my heart.”

Back in Djiboutiville, one hand shielding half his face, he rested the other against the curtain. He wanted to move, to stand, to get out of the yellow room, to meet his friends in Place Rimbaud, yet felt weighted. There was a mourning of time passed, five years wasted, the loss of Araso, and of his mother. Memories flooded in, shape-shifting figures, blurring lines between truths and falsehoods. The skirmish in the mountains that gave Sami the chance to escape, like stories under the damas tree, seemed almost fantastical.

“There are two things I will never forget,” he said. “Being kidnapped and having seen my friend killed in front of my eyes . . . The boys that come from the farms in Ethiopia, they don’t think. Even if you tell them about the war in Yemen or about Abdul Qawi, they close their ears. Any word of trouble and they will just answer you back with the same remarks like ‘Allah will save me’ or that their ‘dilal can’t be lying’. If you decide your future on the cheap, then for sure something bad will happen.”

Three thousand dollars sat wrapped in a bundle, passing for a giant’s sack. The heavy bag stayed exactly where it was on the fur-covered dashboard as Said veered sharply around a bend on the rutted coastal highway into Obock. Eventually, the smuggler’s truck screeched to a standstill and, through a slim gap in the tinted windscreen, Said caught sight of them. Two teenage boys, dead under a tree.

For a brief moment, the clamour that had been building inside the packed vehicle ceased. The men and women crushed in the back of the pick-up dusted off their disagreements. In unison, each with their palms turned upwards, the melancholy incantation came: “Inna lillahi wa inna ilayhi raja un.” We belong to God and to Him we shall return.

A slow-moving column of vehicles had already passed the nameless boys that morning. Perhaps supposing them to be sleeping, hundreds of migrants and refugees had simply walked by, their heads bowed against the dust storm. In the already unbearable surging heat, their need to find cover was pressing.

Had the two boys walked for another half an hour, a spit of tarmac would have led them to Obock town and the high, white screed walls of the Migrant Response Centre, where they could have sought help.

Kassim was one who had made it. Limping to the centre on a single flip-flop, the 15-year-old was shouldered by his smaller friend. In jeans cut off to just below the knee, he clenched a near-empty shopping bag containing all that he owned. Taped all over his face, sheets of taupe sticking plasters barely masked his agony. Charting an unlit route in the cool of night, when checkpoints are easier to pass, Kassim had been hit by a car that didn’t stop.

In the far corner of the yard, closest to the water supply where residents clean themselves and their clothes, brimming vats of sticky rice sat on the boil for lunch. Holding up a wooden spoon longer than his arm, 16-year-old Abdi stopped stirring. Mopping his brow, he was careful not to wipe away the semblance of a beard, sketched on to his jawline with biro. Having escaped enslavement in Yemen, Abdi sized up Kassim and his friend, his soon-to-be roommates.

Logged as numbers 24 and 25, their names were taken down in a thick blue ledger reserved for unaccompanied minors. The Migrant Response Centre’s manager, Mohamed, showed the boys into the compound. Kassim was taken to the hospital, a rudimentary single ward, pungent with the biting odours of antiseptic and bleach. Patched up and given fluids, he lay on one of the four plastic-covered beds dressed with clean white sheets, his bag stowed beneath him.

The Migrant Response Centre was constructed little more than a decade ago, and Mohamed has been working there ever since. “It was when we started to hear the name Abdul Qawi. Before, it was just a small number of Somalis coming through Obock but now it’s nearly all Ethiopians. Around 300 a day,” he said. Under galvanised roofs, dormitories are hemmed into the boundary walls, laced at their upper edges with repeating flower patterns. Shapes formed by semi-open concrete blocks, blowing in clouds of dirt but too high to see out of. Mattresses dispersed here and there on floors are partitioned by hung mosquito nets. Shrouds that cast a synthetic blue haze across bare spaces, assigned for a constant turnover of about 500 men, women and children.

Funded by the UN’s International Organization for Migration, staff at the Migrant Response Centre do their best to offer lifelines. Covering a vast terrain, outreach teams set out to warn travellers of the dangers that lie ahead, at sea and in Yemen and Saudi Arabia. Words and realities that more often than not fall on deaf ears. Mohamed spoke of how the heat kills so many and of human remains, all too regularly discovered by the roadside. “Just this summer we found a corpse only metres away from the entrance. He was so, so close.”

Leaning back on the chest freezer, the guards sneaked a look at Aisha’s screen. Behind the bright pink phone case, their queen was dropping effects on to her latest TikTok post. For her third lip-syncing video of the day, the beats of Puntland favourite Sharma Boy were overlaid with animated broken hearts. Wagging at the camera, her face was reflected back, slimmed by a glamour filter. Aisha is the heiress to a matriarchal people-smuggling empire. She sat under the shade of her mother’s corrugated-iron preserve on the edge of Bosaso, Somalia, the favourite child.

Her two young sons manned the counter of the shop, sucking lollipops that have dyed their tongues blue. The store sells Superb- and Comfort-brand biscuits and soft drinks, all priced at an exacting $1 minimum, along with chargers, T-shirts and an array of goods aimed at a captive market. On the other side of the semi-open shack, a few guards were gathered in the café area, taking a break from the oppressive afternoon sun. Dressed all in black, Aisha’s mother, Hoyo Oromo, surveyed her realm, a clutch of dormitories and shelters housing migrants and refugees. Her moniker, meaning “Mother of the Oromo people”, is hand-painted in large, blue letters on the walls around her. Returning to her father’s home town following the fall of Siad Barre’s regime in the early 1990s, she was quick to see a business opportunity. “Back then I used to see only Somali refugees but then Ethiopians began arriving in town,” she recalled. “They’ve never stopped. They all know my name now, even in Ethiopia.”

The Mother of Oromo’s pre-eminence began simply enough with a shop, set up on the margins of Bosaso, the renowned smuggling township near the tip of Africa’s horn. As the old guard of smugglers died, or were killed in disputes over stakes in the lucrative people trade, Hoyo Oromo seized her chance. She now controls a human-trafficking syndicate that stretches from Jijiga in Ethiopia to Las Anod in Somalia and Ataq in Yemen. “It’s hard to remember the numbers, but each day we receive around 700 to 800 Ethiopians. Usually, three trucks arrive every day and each carries 250. The numbers used to be less but now they just keep increasing, and now there are so many women.”

As the call to prayer resounded from the two neighbouring mosques, hundreds of weary tahriib emerged from the shadows. She nodded to her guards to get back to work. Watched over like this, the tahriib cannot wander far from the encampments sited on either side of Hoyo Oromo’s headquarters. Divided into separate quarters for males and females, the roofless dormitories are a grim resting place. Scum-covered water fills a trough on the outer edge of each compound. It is all that is available both to drink and for the two mud latrines. With only spare rations of rice served once a day, many inside lie hungry and sick. Skin infections are commonplace, as are untreated wounds, inflicted during beatings or incurred on the journey.

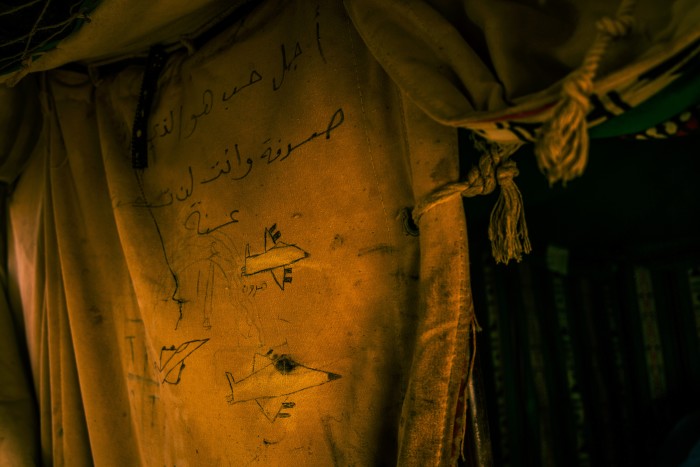

Dunia sat in a daze, her left eye bruised and swollen. Her legs were outstretched, a cotton dress bundled into a red shawl on her lap her only possessions. When Hassan, another guard, emerged from his room, Dunia and her companions dared not look up. Behind a curtain patterned with the Apple logo, their keeper’s private lodgings were replete with decorative plastic flowers, a wooden double bed with mosquito net and dressing table. Two whips sat propped up on the headboard. Behind the purdah, four 14-year-old girls who had dreamt of new lives in Saudi Arabia were holed up in what was effectually Hassan’s private rape chamber. He looked at them gleefully. “They will find work more easily because they are young.”

Hassan swaggered through the compound gulping ice-cold water from an insulated flask, taunting his thirst-quenched detainees. Like the rest of the guards, he readily admitted to participating in torture. “It’s a very profitable business,” he said. Hassan joined his colleague Jibril. The pair sat awkwardly, chewing on leaves of qat, a mild narcotic. There is nowhere really comfortable, not even in the guard’s room. They told stories; they laughed, brushing away requests for mercy from any of the tahriib brave enough to approach. They indulged themselves in recounting horrors they had seen and inflated rumours they had only heard. The name Abdul Qawi was mentioned.

Hassan lurched back. “I get afraid when I hear that name. It’s like seeing a ghost. The first time I started to hear about him was around eight years ago, when I was working in Yemen. There are others that saw him, but I never did. One of the tragedies I witnessed with my own eyes was when one of his men caught a migrant. They stitched his lips together and told him that they would make him a new mouth. They took a knife and that’s what they did.” Hassan sucked in loudly and slowly ran his finger from cheek to cheek.

Jibril had his own theories: “He’s an Arab man. He’s a thief. He’s a hunter. He is everywhere. You will always find him. In Yemen his people are all over the shore waiting so that when the tahriib arrive, they bring them to him. I think Abdul Qawi is an operation, a group of people. Maybe he’s the boss, but now everyone that works for him uses his name.”

Having uploaded her quota of TikTok videos for the day, Aisha came in to look in on the latest truckload of 69 women and girls to have arrived. Obsessively checking her smartphone for reactions to her post, as if oblivious to the pervading sense of dread, she briefed the new arrivals. It would be at least another week before they are escorted on to boats. Prevailing summer monsoon winds would make the crossing even more treacherous.

Drownings are common. This June, for instance, a smuggler’s boat making its way from Bosaso forced passengers to jump overboard more than four kilometres off the coast of Yemen in rough weather. Fifty-six refugees and migrants died. A further 140 were unaccounted for. Nearly all were young and spent hours fighting for their lives in the water.

Aisha made reassuring statements about powerful boat engines and new technology. She said she would keep the new arrivals safe. And then she readily cast blame. “Every migrant that has died or been killed is because of Abdul Qawi. He is a bad man. The tahriib don’t want to go through Djibouti because of this man. It means now there is less fear of travelling through Somalia. It is good for us.”

On a waning tide, the flat seabed stretched between the boundless plains and the now-faraway shore. The wind had blown all traces of footprints from the sand, left smooth as buttercream run over with a palette knife. Up close, its surface was speckled with sharp twigs, blue caps from water bottles and coloured sprigs of plastic bags. The only feature was a solitary acacia tree, just visible in the clammy dawn haze.

Fantehero, a village near the port of Obock in Djibouti, is one of a number of open-air staging posts where the tahriib gather, bound for Yemen, just 100 kilometres away. From within adjacent huts in the village, spectral figures draped in oranges and reds emerged, carrying pots and firewood. Wives and daughters of local dilals getting ready to cook and make money. Soon, the smells of cooking woke the shrouded figures sleeping under the tree.

Mohammad Siraj was the first to rise. After finding his flip flops, he scanned the scene, looking for Omar. The youngest of the group escaping war in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, Omar said he was 15 but was probably much younger. His small feet were just visible, moving from side to side, amid a line of sleepers coming round.

Siraj fumbled in his shorts, searching for the last of his birr. A roll of small banknotes that might do him no good in a day or two. For now, he bought himself a round of overpriced bread and one for the boy. He considered his options. Better to keep some funds for later. There was no knowing when the order to move out might come.

Along a dry river bed, groups of women secreted themselves away, finding private spaces behind boulders. Climbing up, Fathima revealed herself, holding hands with a girl dressed in a bright pink hoodie. From their vantage point, they looked curiously at those digging down into the channel with their bare hands for water. It is safer than risking drinking from the well, where a tethered bucket glugs up a soup of rubbish. After eight days on the road, Fathima was exhausted but too anxious to rest properly.

Back beneath the trees, a sense of foreboding prevailed. Conversations did not come easily. It was not until later in the afternoon that a man crouching on his heels with a small black pocket book was first noticed. His head on one side, he mouthed numbers. He was counting. There was no cue to come forward yet the tahriib began to file towards him. As each one gave their name, the dilal wrote.

With each stroke of the pen, Siraj became increasingly unsettled. He had forgotten to look at where Omar’s name came, not wanting the orphan to travel alone. Among the group, agitated whispers built. In need of reassurance, some of the tahriib told the dilal they were with Abdul Qawi. When, they asked, would they meet him? Would he be there when they arrived in Yemen? Was he here now? The quiet dilal simply nodded. For the first time, Siraj wondered if he would ever return home.

Later in the evening, nearly 200 strangers stood in the pitch dark, anticipating the journey ahead. They were waiting to make the short escape across the Bab el-Mandeb, the 30-kilometre-wide channel traversed by small boats in a matter of hours. The so-called Gate of Tears is renowned as a perilous strait, a turquoise corridor dotted with islands and submerged, shifting shelves.

Then came the hum. At first distant, the reverberating noise grew louder. One after the other, a column of trucks hurtled around an escarpment. Then, rising up on to the plateau’s ridge, the convoy went dark, switching off its headlights to avoid detection by coastguard patrols. In a shower of sand, the vehicles came to an abrupt halt, recklessly close to their intended payload.

Wrenched apart from brothers and chaperones, some of the women were taken along with a group of boys in faded puffer jackets. Bundled together on to the back of the Toyotas, the youngest and prettiest were selected, destined to be sold into slavery. Fathima and Omar were gone. They disappeared into blackness.

As the highly orchestrated fiasco played out, everything became dreadful. The dilals worked, calling out names. Male and female; Oromo, Tigrayan and Somali; the fit and the injured, divided into lines and then loaded on to trucks. Groupings that may or may not have replicated those in a notebook. Skirting along thick tracks cut into the desert floor, the drivers lurched away in a cloak of dust.

Inside a lorry, Siraj sat hunched, one of a crushed group all shaken to the core. As the doors to the enclosed cargo bed were flung open, the dilal, quiet up until now, roared, screaming commands in French. “Courir! Cacher!” Run! Hide!

Disoriented, the passengers jump down in turn, keeping low. Hearts hammering, their quick exit was impeded. Each step they took they subsided deeper into the broad viscous mudflats that surround Godoria’s mangroves. A reckless race, headlong into an onshore wind.

A panicked few ran like lemmings to the sea. On the upper stretches of the beach, awash with layers of dried seaweed and debris, others sought out hiding spots. Remembering instructions, they sheltered in the dunes and behind the fibrous upturned hulls of smuggler’s boats that sat like whale carcasses at intervals along the coast. Above, an expanse of stars fell down to every horizon like the ribs of an umbrella.

From the shallows, the painted bow of a narrow craft emerged, pulled over the breakers by its Yemeni crew. A frenetic scramble ensued and, in minutes, the boat was gone, the sound of its engine lost to the blowing swells. In its wake, only footprints and still-full bottles of water, left in haste along with pair after pair of shoes — laced walking boots, petite sandals with heels, pink suede brogues — footwear meant for new lives that would now begin in bare feet.

Note: Some of the names in this story have been changed

For more than 15 years, photographer and author Alixandra Fazzina has been reporting from the shores of the Gulf of Aden, weaving together intimate stories of people on the move. Her first book “A Million Shillings” documented the flight from war-torn Ethiopia and Somalia. She is a laureate of the UNHCR Nansen Refugee Award and was shortlisted for the Prix Pictet in 2015.

Follow @FTMag to find out about our latest stories first and subscribe to our podcast Life and Art wherever you listen