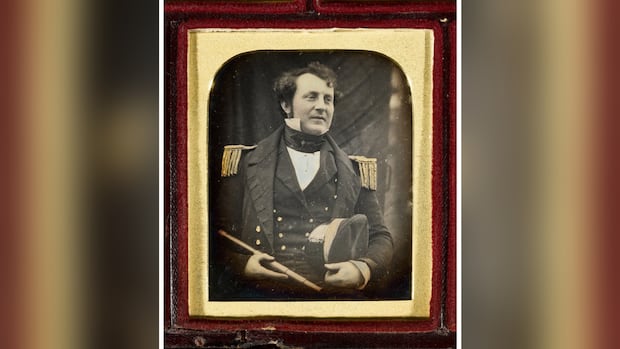

The skeletal remains of a crew member from Sir John Franklin’s failed 1845 Northwest Passage expedition have been given a name: James Fitzjames.

He is only the second member of the crew to be positively identified though DNA and genealogical analyses, joining John Gregory, engineer aboard HMS Erebus, who was identified in 2021.

It’s believed Capt. Fitzjames, a senior officer on the HMS Erebus, attempted to help the 105 sailors of the Franklin expedition clear the Northwest Passage in his final days of April 1848. However, the 1845 exploration to find the Northwest Passage ended in starvation, death and, according to marks on Fitzjames’s jawbone, cannibalism.

Researchers from Lakehead University in Thunder Bay and the University of Waterloo, both in Ontario, worked together in the joint study.

Stephen Fratpietro, technical manager for the Lakehead University Paleo-DNA Laboratory, was responsible for getting DNA from the samples and matching them to descendants. He said the remains were found about 80 kilometres away from where they deserted the HMS Erebus and made their way to King William Island, Nunavut.

James Fitzjames is the second crew member of the ill-fated Franklin expedition who has been identified. His skeletal remains were detected through DNA research. The CBC’s Mary-Jean Cormier speaks to Stephen Fratpietro about how that works.

Evidence of cannibalism

It was through a DNA analysis of the captain’s jawbone found on the island that the team found new insights about the expedition’s sad ending.

“On this mandible, they did find cut marks or evidence of cut marks,” said Fratpietro. “So, it looks as though that this individual, or James Fitzjames, he was possibly cannibalized and that was probably his final situation that he was in. It was a dire survival situation and whoever was with him at the time probably used him to survive.”

In the 1850s, the Inuit were reported to have seen evidence that survivors had resorted to cannibalism. Those accounts were later corroborated in 1997 by the late Dr. Anne Keenleyside, who found cut marks on nearly one-quarter of the human bones at the site, NgLj-2.

DNA and genealogical analyses

At this particular site, Fratpietro said, there are 13 individuals consisting of around 451 bones.

“We’ve identified two individuals at this point and we’d love to be able to identify individuals in the future.”

However, reaching their goal of identifying every member of the Franklin expedition is not easy.

He said it is all based on living descendants providing their DNA and them being able to compare the living descendant DNA to their library of DNA that was achieved from working on the rest of the samples.

Living descendant

The DNA donor who matched the sailor’s DNA was a second cousin of Fitzjames, five times removed, and is linked to him through two of James Gambier’s sons: Fitzjames’s grandfather, also named James Gambier, and his brother John Gambier, who was Fitzjames’s grand-uncle.

Fratpietro said while his team was initially apprehensive about mentioning that Fitzjames was cannibalized, they wanted to present the facts and were excited to share the results with his living descendent.

“The living descendant was a little bit taken aback, but he wasn’t upset about it or anything,” said Fratpietro. “He said something to the effect that he is kind of glad that his ancestor wasn’t the one doing the cannibalizing, but at least he was eaten instead.”

Going forward, Fratpietro’s team will use this research to help them figure out what exactly happened during the expedition, including which sailors went, how they migrated from their ships and where they ended up.

“It’s just great that we can do this kind of research at Lakehead University, and it does change history,” said Fratpietro. “We are asking the public if they think that they have a member of the Franklin expedition somewhere in their family tree to contact us. We ensure that they’re a good candidate for DNA testing and then hopefully they can help us identify more of these individuals that we have found up north.”

This research was funded by the government of Nunavut and the University of Waterloo.