Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

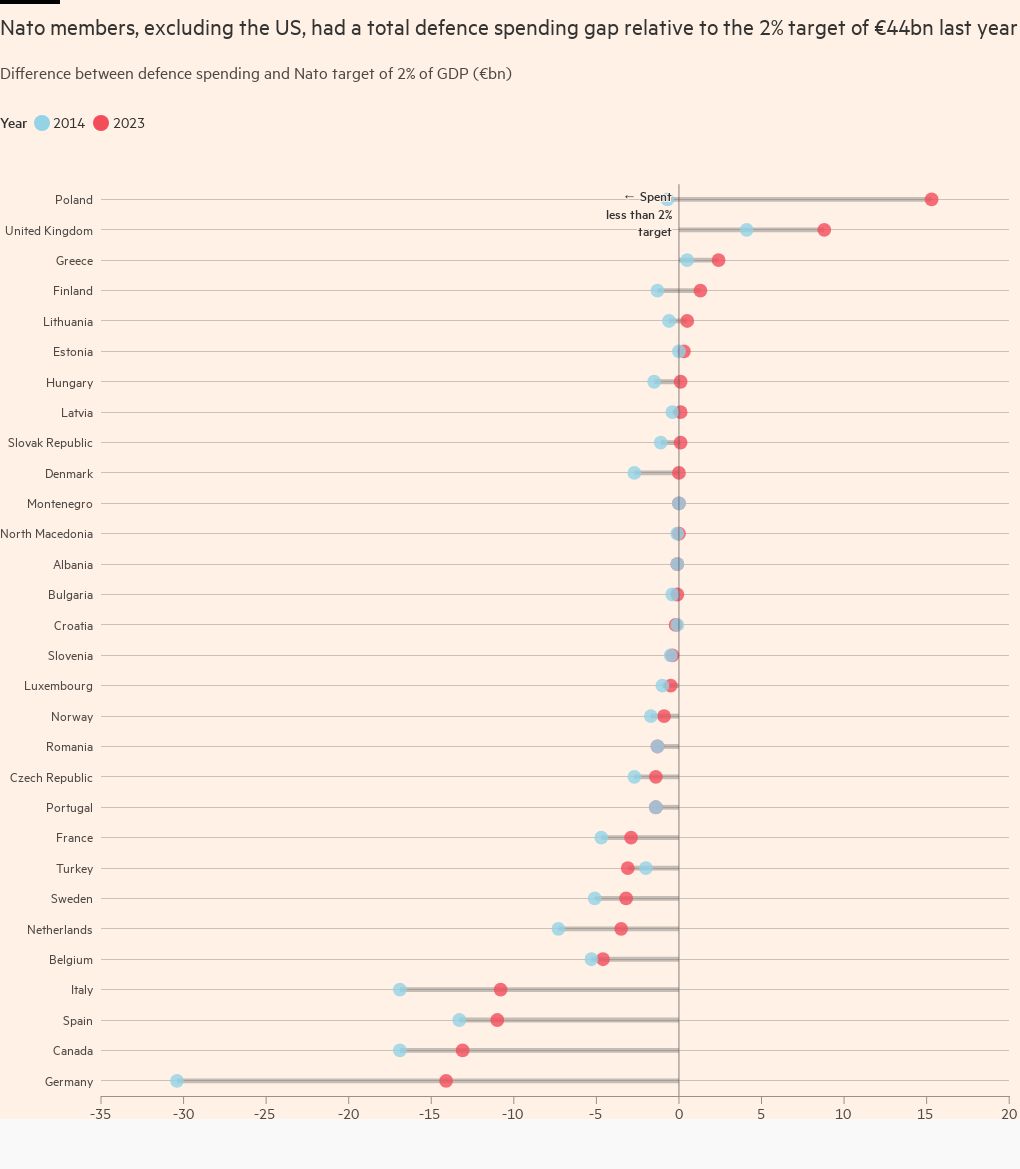

By buying weapons at a record pace, Poland has become a star member of Nato. Warsaw will spend 4.1 per cent of Poland’s GDP on defence this year — just over twice the Nato target and ahead of the US. But when it comes to manufacturing its own military equipment, Poland remains a laggard.

Poland’s shortcomings were exposed in March when only one Polish company was among 31 projects selected by the European Commission to boost EU ammunition production. That meant assigning Poland €2.1mn from a funding package worth €500mn.

The setback added to the tensions between Donald Tusk’s coalition government and the rightwing opposition led by the Law and Justice (PiS) party which lost power last December.

Former PiS defence minister Mariusz Blaszczak sarcastically congratulated “Donald King of Europe” for getting 0.42 per cent of the EU’s ammunition fund.

But current defence minister Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz blames botched tenders and manufacturing problems on a “tragic” legacy of PiS mismanagement and insufficient funding for the domestic defence industry.

One of Kosiniak-Kamysz’s priorities is overhauling the Polish Armaments Group (PGZ), the state-controlled holding company that he claims lost its way amid a merry-go-round of CEOs orchestrated by PiS during its eight years in power.

Some analysts say the dominant role of PGZ, which groups about 50 manufacturers, underlines Poland’s over-reliance on unwieldy state-owned companies.

The country accelerated weapons procurements not only to counter Russia’s aggression but also to replenish stock sent to Ukraine following Moscow’s all-out invasion in 2022. Even so, the scale of Warsaw’s purchasing has been eye-popping.

In 2023 Poland ordered almost 500 Himars artillery systems from Lockheed Martin — more than the number stationed in the US. Last month Warsaw finalised a $10bn contract to buy 96 AH-64E Apache attack helicopters, turning Poland into the Apache’s top user after the US military for which it was developed.

Mirosław Różański, a former commander of Poland’s armed forces who now chairs the Senate’s defence committee, told me earlier this year that Poland could have ordered just 130 Himars and 48 Apache helicopters, but PiS wanted “big numbers” to show citizens that it guaranteed their security.

Tusk’s government has continued the overseas buying spree, pledging to maintain its Nato spending leadership even if this puts further strain on public finances. Next year’s budget raises defence expenditure to a record 187bn zlotys ($48.9bn), or 4.7 per cent of Poland’s GDP.

At the same time, the Tusk government is demanding that more weapons be assembled in Poland. It has talked about having 50 per cent of future military spending tied to companies that manufacture in Poland.

Last month Kosiniak-Kamysz hailed a $1.2bn contract for additional Patriot air defence systems “a great achievement” because they will be built in Poland. Warsaw also recently ordered 180 South Korean K2 tanks that are due to be kitted out in Poland for the first time.

And after winning plaudits for its drones and radios, the privately held WB Group agreed this month with subsidiaries of South Korean defence company Hanwha to collaborate on submarine technology and guided missiles.

But only 1.1 per cent of this year’s defence expenditure was allocated to research and development, which some analysts consider to be insufficient to guarantee a strong pipeline of Polish weaponry.

Poland has successfully produced some weapons, including Krab howitzers that have helped Ukraine’s army fight Russia. But Poland has struggled with some larger projects, notably a Ślązak patrol ship that its navy needed 17 years to build.

And Sung Il, South Korea’s deputy defence minister, told me that while Seoul welcomed the transfer of tank technology to Poland, the plan is on hold because Polish assembly plants are in need of upgrades, including to provide spare parts. “I didn’t expect these kinds of problems,” he said.

Tusk’s government will have to tackle such issues if it is to meet goals to increase local production and convince Polish military commanders to reduce their focus on foreign equipment.

Paweł Poncyljusz, a Polish politician who also chairs defence company Polska Amunicja, points out that when a weapon produced domestically is not seen as being at the same level as foreign options, then it is “not the solution” for the country’s generals.

Poland’s hope is that its big spending will eventually lead to more domestic expertise.