Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

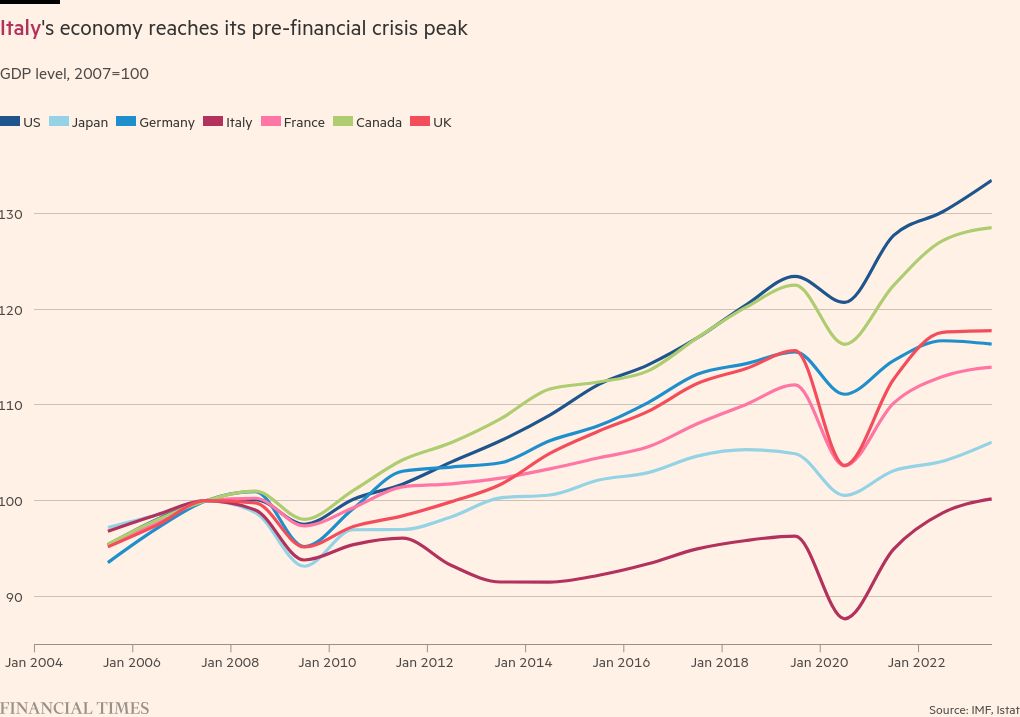

You might be forgiven for missing a milestone for the Eurozone: Italy’s economy was finally back to its pre-financial crisis peak. Getting back to where it started has taken over a decade longer than most other advanced economies, but let’s not be fussy about the details for now.

Buried in a dull press release about Italy’s revisions of historical national accounts, Istat, Italy’s statistics office, said on Monday that the economy grew stronger than previously thought in 2022 and 2021.

For 2023, Italy’s output grew by 0.7 per cent, 0.2 percentage points less than previously estimated. However, in 2022, the economy expanded by 4.7 per cent, 0.7 percentage points more than previously estimated. And in 2021, the economy grew by 8.9 per cent, a 0.6 percentage point upgrade to previous data.

“As a result of the revision, 2023 GDP volumes stood at a level for the first time higher than the maximum reached before the 2008 financial crisis,” says Istat. According to the new data, Italy’s GDP is now 0.2 per cent higher than its peak in 2007. Evviva!

Reaching its 2008 output levels “it’s good news for Italy. It’s good news for the debt sustainability of Italy,” said Samy Chaar, chief economist at the bank Lombard Odier.

Istat said it revised down Italy’s public deficit to GDP as a result of a larger economy. But in many ways, the milestone is a reminder of how weak its economic recovery has been compared with other advanced economies.

Canada and the US reached their 2007 output levels in already in 2010 and last year output volumes in the US were one-third larger than then. Germany and France reached that milestone in 2011 and their economies are now about 15 per cent larger than in 2007. The UK economy was larger than in 2007 a decade ago and it is now up 18 per cent from that level.

“The 2015-2019 recovery was not strong enough to bring output back to pre-global financial crisis levels with the 2008 GDP level reached only last year. This is in stark contrast with other advanced economies,” said Nicola Nobile, an economist at the Consultancy Oxford Economics.

Actually, Italy’s economy is not much larger than at the turn of the century, compared with a 60 per cent expansion for the US, 30 per cent growth for France and Germany, and 40 per cent for the UK.

This is the result of a prolonged stagnation in productivity, argued Chaar, who attributed the trend to a “lack of investment and innovation” coupled with an “inadequate” policy setting.

“Policy has been too restrictive for too long for Italy, and that what has led Italy into this kind of stagnation,” said Chaar.

This is combined with a population that is rapidly ageing and reducing. Italy has the highest median age across the EU and one of the lowest fertility rates in the world. Low labour force participation and weak skills are not helping growth in the peninsula.

The statistics office showed that Italy’s growth in the last three years was helped by the generous tax relief on home improvements introduced in 2020, with investment growing by 32 per cent between 2019 and 2023. (We wrote about that in March.)

Chaar added that the economy is benefiting from rising real wages as inflation dropped from its multi-decade high of 2022, as well as from the Next Generation EU investment programme.

However, according to some economists, structural problems mean that the prospects for Italy’s economy are underwhelming.

“Over the medium term, we think the Italian economy will return to a path of subdued growth and undershoot its peers,” said Nobile. “An ageing population, lower education levels relative to its peers, and subdued investment will keep potential growth extremely low.”