Emirati student Shaima lives in Abu Dhabi with her four siblings and parents. But she says her seven-person household is small — her father grew up alongside 11 brothers and sisters in the days when the region’s families were legendarily large.

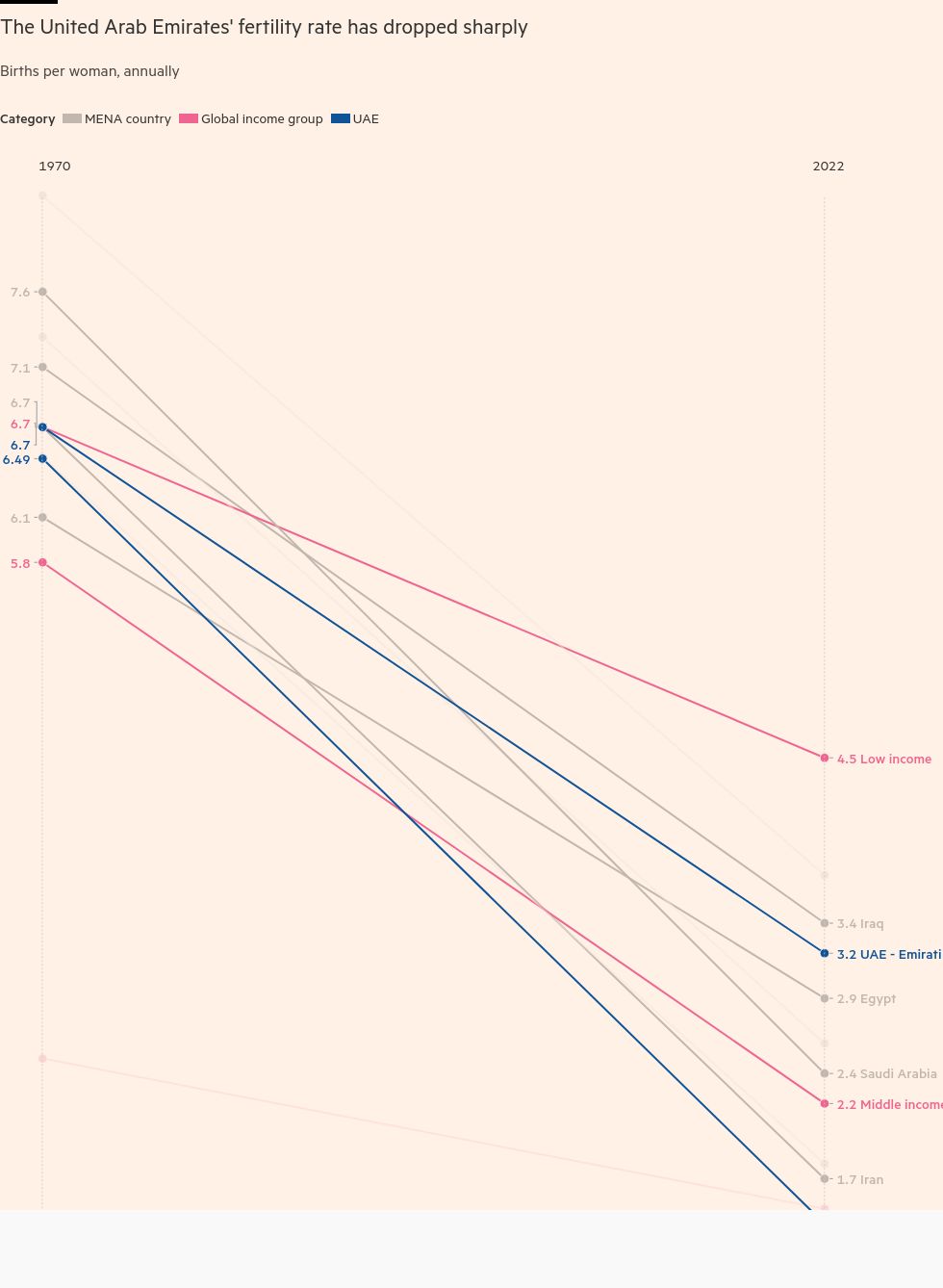

The generational downsizing in the 21-year-old’s family reflects a dramatic social shift across the United Arab Emirates: Emirati women bear about half the number of children their grandmothers did in 1970, with the fertility rate down from 6.7 per woman in 1970 to 3.7 by 2017, according to official data.

In a country that lures millions of migrant workers to power an economy that has grown at breakneck speed since the 1960s, the trend has prompted many Emiratis to worry that they belong to a dwindling minority in their own country — and spurred authorities to offer more support designed to encourage large families.

“Us Emiratis are a minority in our own country,” said Shaima, who called the trend “upsetting”. Expatriates form 93.5 per cent of the UAE population of about 9.5mn, according to the UN.

“Why is demographics a sensitive issue?” said William Guéraiche, associate professor at the University of Wollongong in Dubai. “Because this imbalance will grow between the Emiratis and foreigners, and Emiratis feel more and more under siege, rightly or not. But this is the general perception, and the authorities have to deal with that.”

The Emirati fertility rate, which government figures put at 3.2 in 2021, has halved in the past two decades, according to Luca Maria Pesando, associate professor of social research and public policy at NYU Abu Dhabi. He described the drop as “very fast for a demographic transition”.

Although 3.2 exceeds the so-called replacement rate of 2.1 live births per woman, meaning the number of Emiratis is not falling, the authorities are concerned about the speed of the decline, said Pesando, who is working on plans to open a state-funded demographics research centre at NYU Abu Dhabi. “If this has halved [in 20 years], maybe it can halve again,” he added.

One former Emirati official said it was almost inevitable the Emirati minority would dwindle as a proportion of the resident population.

“If we are successful in . . . attracting more people into the country, this automatically diminishes us as a percentage,” he said. “How do you counter that? Encourage people to have more kids.”

The government has traditionally offered generous subsidies to local families, from grants and loans for housing and weddings to marriage counselling and help with childcare.

But a new “Emirati Family Growth Support Programme” in Abu Dhabi, the emirate which includes the UAE’s capital city, focuses on family size, with incentives such as reduced loan debt on the birth of a fourth, fifth and sixth child.

The government wants Emirati families to “grow their numbers because they play a vital role in achieving social stability and preserving national identity”, said Hamad Ali Al Dhaheri, under-secretary of Abu Dhabi’s community development department.

The UAE does not publish detailed national statistics on population composition. But data from Dubai, the region’s business and tourism hub, shows expat population growth still outpacing that of locals. While the number of Emiratis in Dubai increased 31 per cent between 2015 and 2023, the number of foreigners rose by 46 per cent.

Expatriates are largely transient and have scant chance of becoming Emirati citizens, but the UAE has in recent years offered longer-term visas and encouraged foreigners to buy property and invest in businesses.

The Emirates are expecting a further influx of overseas workers as they pursue ambitious plans for the economy, with Dubai alone forecasting a population of 5.8mn people by 2040, from around 3.5mn now.

The millions of migrant workers, from domestic help to oil engineers and finance professionals, have helped drive rapid growth since Abu Dhabi started exporting oil in the 1960s and Dubai established itself as a trading hub. In just a few decades the country has moved from a largely impoverished tribal society to enjoying some of the region’s highest living standards.

By 2023 the UAE recorded the Middle East’s second biggest gross domestic product per capita, according to the World Bank.

But the country’s economic success is a leading factor behind its own slowing birth rate, according to observers. Some Emiratis say rising living costs discourage them from having more children. A government worker and mother of one said she was not planning to have more because of the expense of childcare, including education costs.

Academics also argue that smaller families are partly driven by the UAE’s success in encouraging women to pursue higher education and employment and contribute to the economy, which has led many to delay marriage and having children.

The UAE has a high proportion of working women compared with the wider region, with 55 per cent of those aged over 15 participating in the labour force. By contrast the average across the Middle East and North Africa is 19 per cent, according to International Labour Organization estimates.

For 30-year-old Huda, a museum researcher whose mother married at 16 and had nine children, staying at home to raise a family was the last thing she wanted.

“[My generation] were very open to [what we saw in] American and western movies,” she said. “We wanted independence.”

Other UAE policies to help working mothers, such as lengthening statutory maternity leave to 60 days, may not be enough to bring back the big families of the past.

“I know I’m going to be a working mum,” said Shaima, who said she would like four children. “I need to balance between my working life and taking care of my kids. And having a lot of kids is not going to help.”