White Coat Black Art26:30This school’s for family docs only

The people behind a year-old medical school dedicated solely to turning out family doctors say the small program based in Oshawa, Ont., is disrupting traditional medical education in a way that could help solve Canada’s shortage of family physicians.

“The big idea here is to preselect a group of students who not only want to become doctors, but they want to become family doctors, and right from the outset to surround them with all the wonders of family medicine,” said Dr. Jane Philpott, dean of Queen’s University’s Faculty of Health Sciences, and former federal health minister.

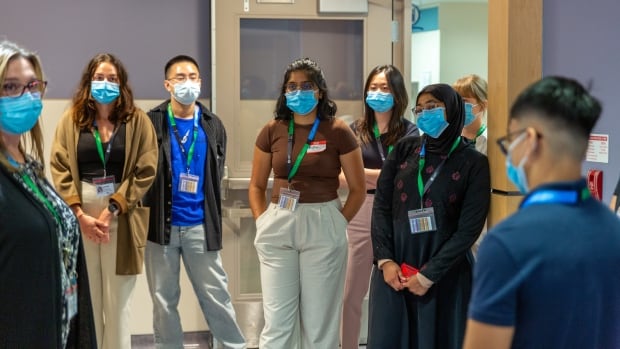

The first 20 students in the Queen’s-Lakeridge Health MD Family Medicine Program began their studies in September, 2023. The school is a partnership between Queen’s University, which also operates a traditional medical school at its main location in Kingston, Ont., and Lakeridge Health hospital in Durham Region, just east of Toronto. The satellite campus is located right in the hospital.

But critics say, while it’s a good initiative, the effort is a drop in the bucket and that solutions to the overwhelming primary care shortage lie elsewhere — from training more nurse practitioners to removing barriers for foreign-trained doctors.

Guaranteed residency in family practice

In traditional medical school, students are admitted into a general program, and learn the various systems of the body in mostly classroom settings, before beginning rotations in various specialities — obstetrics, cardiology, emergency medicine, to name a few — in their third and fourth years.

When their four years are up, students decide on a specialty before entering a cutthroat competition for coveted residency positions anywhere in the country. It’s a system that’s increasingly pushed graduates toward prestigious, high-paid specialties, and not to family medicine.

Students at the Queen’s Lakeridge program acquire all the same knowledge required to be a doctor, but through the lens of family practice, Philpott told Dr. Brian Goldman, host of CBC’s White Coat, Black Art.

She said that students are selected for a commitment to family practice and are taught largely by family physicians, then transition from their M.D. program into guaranteed family medicine residency positions in the Durham region.

The program is six years instead of four because the residency program is baked in — without the Hunger-Games-style battle for position.

“There’s no competition between us,” said second-year student Laura Vresk, who was a dietitian at Sick Kids Hospital in Toronto for more than 15 years. “Our class is really more like a big group of friends or a family.”

Vresk said another big difference is the immediate immersion in clinical environments, beginning around the third week.

Dr. Natasha Aziz, a Durham-area family physician and the school’s curriculum director, says students spend 20 half days in their first year in a family medicine office within Durham region.

“When they do that, they’re seeing real family medicine that is quite typical of what’s happening in Ontario and probably in Canada as a whole in family doctors’ offices. So it’s not sugar coated.

“They see, you know, patients come in for a 15-minute appointment with an entire lifetime of problems.”

An issue of scale

But critics such as health policy analyst Steven Lewis say that while the effort is admirable, it’s not an approach that can scale fast enough to address the shortage of care providers.

“There’s 6.5 million Canadians who don’t have a regular source of primary care,” said Lewis, who is a research consultant with Simon Fraser University’s Faculty of Health Sciences.

A full roster of patients is 1,300 or 1,500 people, he said. “It will take a net increase of thousands, probably 4,000 to 5,000 family doctors.” The Queens-Lakeridge program, with 20 students, and other new medical school initiatives will likely yield “a few hundred” entering the field each year.

With the population of doctors also aging, Lewis says “we’re losing at least that many” each year to retirement.

Data from the Canadian Post-MD Education Registry shows that 1,443 med school grads entered their first year of family medicine residency in the year running 2022 to 2023, but it’s less clear how many of those stick with family medicine.

It also costs much less to train a nurse practitioner, he says.

Lewis says the only way Canada can solve the primary care crisis in the span of three to five year, is by providing registered nurses with the opportunity to do the two-year Masters degree required to become nurse practitioners.

Given there are more than 300,000 nurses spread across the country, incentivizing even half of one per cent to take the training would yield 1,500 new primary care providers, he said.

Lewis says there’s a great deal of research showing that nurse practitioners can cover “at least 80 per cent” of the scope of a family physician.

For issues that are out of their scope, nurse practitioners can refer to family doctors or relevant specialists.

“It still increases capacity enormously. It allows physicians to focus at the higher end of their scope of practice instead of trying to do everything for everybody and burning out at the same time,” said Lewis.

Philpott said that, along with her role in medical education, she’s also advocating hard for reform to Canada’s systems of delivering primary care, including by improving access to nurse practitioners. There’s a program for primary care nurse practitioners at Queen’s that she says is growing, too.

UBC said in a statement that it doubled the number of students in its nurse practitioner program this fall.

The Ontario government announced funding for a new medical school at York University. However, as CBC’s Patrick Swadden reports, doctors and advocates in the medical community are not confident that more training will solve the province’s primary care crisis.

Foreign trained doctors still not put to work

Economist Armine Yalnizyan, who has an expertise in health-care funding, said Canada has been talking for “at least 25 years” about both a shortage of physicians and barriers for foreign trained doctors to work in Canada.

“It’s appalling to me that we have not yet come up with a resolution to this credential recognition process, something that is expedited, something that has the blessings of the medical community, and something that acknowledges that a lot of those people that are the gatekeepers of that community will be retiring and they don’t have succession planning in place,” said Yalnizyan, who is also an Atkinson Fellow on the future of workers.

The CBC reported last year there may be as many as 13,000 medical doctors in Canada who are not practising because they haven’t been able to access a residency position, the vast majority of which are reserved for Canadian medical school graduates.

While progress is slow overall, there are some efforts underway to reduce barriers. The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Nova Scotia, for example, says it has streamlined the process of providing long-term licensing to international medical graduates.

In 2023 Ontario revived its Practice Ready Assessment (PRA) program for foreign trained doctors, after scrapping it five years earlier, becoming the eighth province put a PRA in place in recent years.

Other med schools take notice

While it not a whole solution to the primary-care crisis, the Queen’s Lakeridge program has piqued the interest of other Canadian medical schools looking to emulate its model of training family physicians.

A new medical school set to open in 2026 at Simon Fraser University’s Surrey, B.C., campus, will have a dedicated family medicine program that’s modelled after the Lakeridge program, the Vancouver Sun reported.

Additionally, when new medical school opens in 2028 at York University in Toronto, 70 per cent of its postgraduate spots will be designated for those who wish to pursue family medicine. Ontario’s provincial government has asked its founders to look closely at Lakeridge, Philpott said.

“There’s not a single solution that is going to solve a complex problem like the lack of access to primary care. It has to be addressed from a whole bunch of angles,” she said, including within the medical education system that has shifted students away from choosing family medicine as a career.

“This is one of those initiatives that we hope will help to make family medicine an attractive choice for our graduating students.”