People may be compelled to inhabit steeper, riskier terrains as urban expansion, climate change, and flood risks at lower elevations increase.

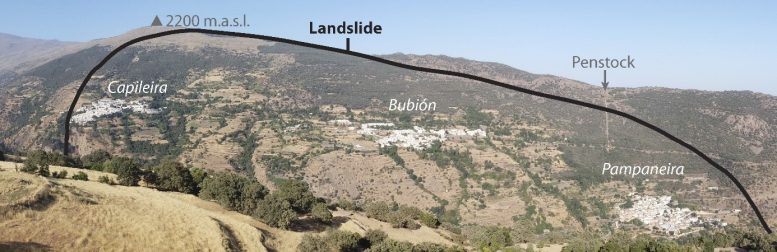

A new study reveals that as cities in mountainous areas expand, more people are being pushed to construct homes on steep slopes vulnerable to slow-moving landslides. These types of landslides are often overlooked in risk assessments, but researchers warn they could endanger hundreds of thousands of people worldwide.

Slow-moving landslides can move as little as one millimeter per year and up to three meters per year. Slopes with slow-moving landslides may seem safe to settle on; the slide itself may be inconspicuous or undetected altogether.

As the slide creeps along, houses and other infrastructure can be damaged. The slow slide can accelerate abruptly, likely in response to changes in precipitation. Sudden acceleration can worsen damage and, in rare cases, lead to fatalities.

Those same slopes may be repopulated years later due to pressure from urban growth, especially when floods drive people from lower-elevation areas. According to the IPCC, nearly 1.3 billion people live in mountainous regions, and that number is growing.

“As people migrate uphill and establish settlements on unstable slopes, a rapidly rising population is facing an unknown degree of exposure to slow landslides — having the ground move underneath their houses,” said Joaquin Vicente Ferrer, a natural hazards researcher at the University of Potsdam and lead author of the study.

The study presents the first global assessment of exposure to slow-moving landslides, which are left out of most assessments of populations exposed to landslide risk. It was published in the journal Earth’s Future, which publishes interdisciplinary research on the past, present, and future of our planet and its inhabitants.

Finding slow-moving landslides

Through landslide mapping and inventory efforts, the authors compiled a new database of 7,764 large slow-moving landslides with areas of at least 0.1 square kilometers (about 25 acres) located in regions classified as “mountain risk” by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Using this database, they explored regional and global drivers of exposure using statistical models.

Of the landslides documented, 563 — about 7% — are inhabited by hundreds of thousands of people. The densest settlements on slow-moving landslides were in northwestern South America and southeastern Africa. Central Asia, northeast Africa, and the Tibetan Plateau had the largest settlements exposed to slow-moving landslides. West-central Asia, and the Alai Range of Kyrgyzstan in particular, also had a high number of inhabited slow-moving landslides.

The study only looked at permanent settlements, so nomadic and refugee settlements were not included.

In all regions in the study, urban center expansion was associated with an increase in exposure to slow-moving landslides. As a city’s footprint expands, new growth may be forced to occur in unsafe areas, including slopes with known slow-moving landslides. But poorer populations may have few other options, the authors point out.

Flooding and future climates

Ties between climatic drivers and slow-moving landslide activation remain uncertain, but in general, scientists think intense precipitation and swings from dry to wet conditions can trigger an acceleration in slow-moving landslides. Those factors can also increase flooding, which in turn may drive people to move to higher ground.

The study found that populations facing increased flooding tended to have more settlements on slow-moving landslides. The strength of that relationship varied regionally; western North America and southeast Africa had the strongest associations.

The study also highlighted a lack of information in poor regions with known landslide risks, such as in the Hindu-Kush Himalayas, and called for more landslide detection and mapping to improve understanding of risks in those areas.

“We highlight a need to ramp up mapping and monitoring efforts for slow-moving landslides in the East African Rift, Hindu-Kush-Himalayas, and South American Andes to better understand what drives exposure,” Ferrer said. “Despite a limited number of landslide inventories from Africa and South America, we found communities in cities are densely inhabiting slow-moving landslides there.”

Even in areas with good landslide mapping, such as northern North America (i.e., Canada and Alaska) and New Zealand, settlements are located on slow-moving landslides. While these weren’t included in the study, they remain important to consider, the authors said.

“Our study offers findings from a new global database of large slow-moving landslides to provide the first global estimation of slow-moving landslide exposure,” Ferrer said. “With our methods, we quantify the underlying uncertainties amid disparate levels of monitoring and accessible landslide knowledge.”

Reference: “Human Settlement Pressure Drives Slow-Moving Landslide Exposure” by Joaquin V. Ferrer, Guilherme Samprogna Mohor, Olivier Dewitte, Tomáš Pánek, Cristina Reyes-Carmona, Alexander L. Handwerger, Marcel Hürlimann, Lisa Köhler, Kanayim Teshebaeva, Annegret H. Thieken, Ching-Ying Tsou, Alexandra Urgilez Vinueza, Valentino Demurtas, Yi Zhang, Chaoying Zhao, Norbert Marwan, Jürgen Kurths and Oliver Korup, 17 September 2024, Earth’s Future.

DOI: 10.1029/2024EF004830