Speaking last month in Jackson Hole, Jay Powell was explicit about what he considered the Federal Reserve’s mission as the US economy emerged from a gruelling inflation shock.

“We will do everything we can to support a strong labour market as we make further progress towards price stability,” the chair said at the foothills of Wyoming’s Teton Range.

On Wednesday, Powell delivered, lowering the Fed’s benchmark interest rate by a bumper half-point cut to 4.75-5 per cent, kicking off the central bank’s first easing cycle in more than four years.

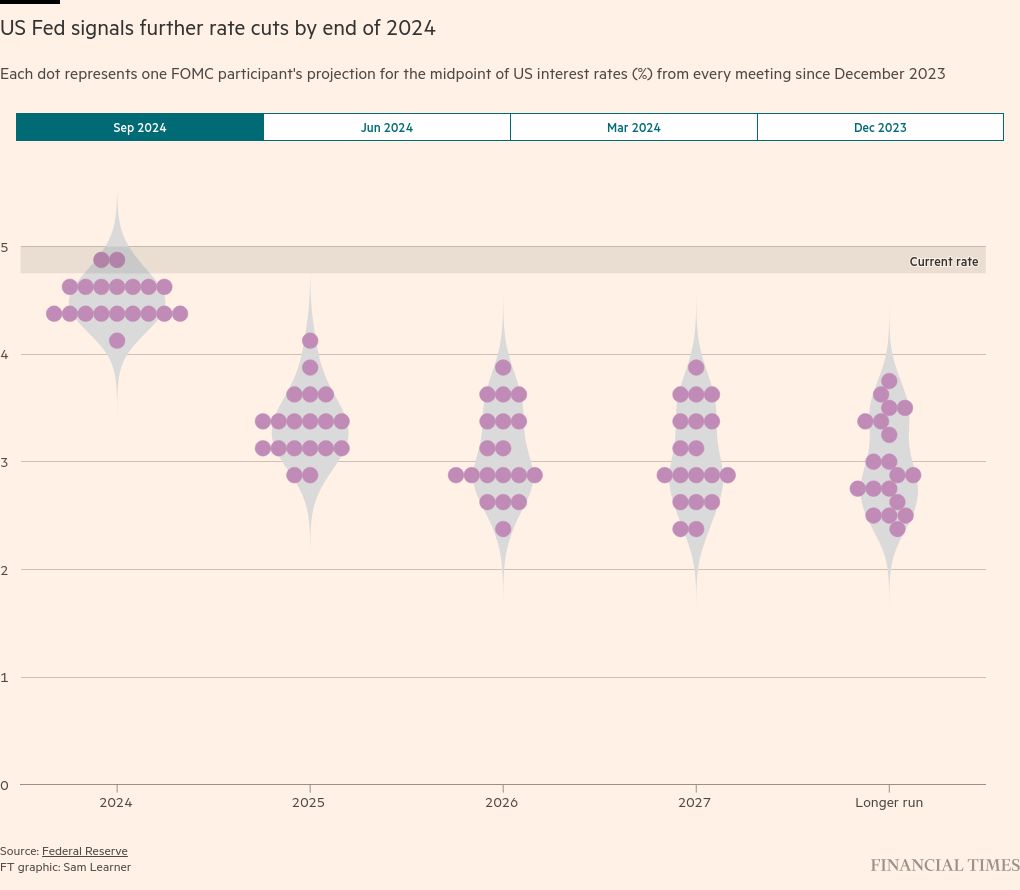

Officials made clear they were not stopping there either, with projections released on Wednesday in the so-called dot plot showing most of the Federal Open Market Committee members estimated the policy rate would fall by another half-percentage point this year followed by a series of cuts in 2025 to leave rates at 3.25-3.5 per cent.

Far from sparking panic — the concern of many ahead of the meeting — Wednesday’s half-point cut was taken in stride by financial markets. Major stock benchmarks and government bonds ended the day barely changed; on Thursday US stock futures rose, as did indices in Asia and Europe.

“It was innovative,” said Peter Hooper, vice-chair of research at Deutsche Bank. “It was taking out some insurance to prolong what is a very good place to be in the economy.”

Hooper, who worked at the Fed for almost 30 years, added: “Powell wants to assure the soft landing.”

The decision is a bold move for the Fed, and coming just weeks before November’s presidential election, has inevitably drawn criticism. Already, Republican candidate Donald Trump has said the cut was either made for “political” reasons — to help Kamala Harris, his opponent in the White House race — or because the economy is in “very bad” shape.

The decision capped a tumultuous period for Powell’s leadership that has encompassed a global pandemic, the biggest economic contraction since the Great Depression, war and severe supply shocks that amplified the worst bout of inflation in 40 years.

Many economists had doubted Powell could tame price pressures without tipping the world’s largest economy into a recession. But two years since the peak of the inflation surge, it has been brought back almost to the Fed’s 2 per cent target while economic growth has remained solid.

In explaining the decision on Wednesday, the Fed chair framed the larger than usual rate cut as a “recalibration” of monetary policy to suit an economy in which price pressures are materially easing while labour market demand is also cooling.

“The US economy is in a good place and our decision today is designed to keep it there,” Powell told reporters at the press conference following the meeting.

In the past, the Fed has typically only deviated from its traditional quarter-point pace of policy adjustments when facing an outsized shock — at the onset of the Covid-19 economic crisis, for example, or when it became clear in 2022 that the central bank had misdiagnosed the US’s inflation problem.

That Wednesday’s bumper cut was invoked without those kinds of severe economic or financial stresses accentuated the Fed’s desire to avoid an unnecessary recession. Diane Swonk at KPMG said if Powell could pull off this kind of soft landing, it would “seal” his legacy as chair.

Rather, Wednesday’s decision reflected the Fed’s efforts to balance the risks confronting the economy. Having brought inflation into range, its focus has shifted to a labour market where slower monthly growth and rising unemployment have raised concerns.

“The Fed is fully aware that from a risk-management perspective getting closer to neutral is probably the right place to be just given where the economy is at,” said Tiffany Wilding, an economist at Pimco, referring to the level of interest rates that neither revs up growth nor suppresses it.

The next step for officials is figuring out how fast they should cut rates to reach that neutral level. In the press conference, Powell said there was not a “rush to get this done”. The dot plot also showed a dispersion among officials not only for this year, but also in 2025.

Two of the 19 officials who pencilled in estimates thought the Fed should hold rates at the new level of 4.75-5 per cent through the end of the year. Another seven forecast only one more quarter-point cut this year. The range was even wider for rates in 2025.

Powell will be tasked with forging a consensus on the FOMC, having met one dissent at this meeting from governor Michelle Bowman, who voted for a quarter-point move. That made her the first Fed governor to balk at a rate decision since 2005.

Achieving that consensus will be made trickier by a muddied economic picture, which shows some stickiness in inflation despite overall improvements and budding weakness in an otherwise solid labour market.

The presidential election also looms large, although Powell reiterated on Wednesday that Fed decisions would be made solely based on the economic data.

Jean Boivin, formerly deputy governor at the Bank of Canada and now head of the BlackRock Investment Institute, warned that the easing cycle could be more “abbreviated” than financial markets expected.

Already traders in futures markets have priced in that rates will fall more than officials forecast, to 4-4.25 per cent by the end of the year, implying another bumper cut at one of the two remaining meetings in 2024. Market participants then expect it to drop to less than 3 per cent by the middle of 2025.

“The outlook for inflation is significantly uncertain,” said Boivin, adding a note of caution about how much relief to borrowers the Fed may be able to provide given that backdrop.

“I don’t think this is the beginning of an easing cycle. I think this is unwinding the tightening.”