Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A strong economy is a wonderful thing. It enables all sorts of industries to flourish — and companies to get away with all sorts of ramshackle corporate structures. Without such tailwinds, management teams have to sharpen their axe if they are to deliver any value at all.

That is one way to read the slow demise of the German industrial conglomerate. Thyssenkrupp spun off hydrogen and is engaged in a complex effort to carve out its steel business. Siemens has a fraction of the sprawl it once did. Bayer has kicked the can down the road on a mooted three-way break-up. The Covestro chemicals unit that it spun out in 2015 is being snapped up by Abu Dhabi’s Adnoc.

BASF, with its six segments and 11 operating divisions, appears poised to join the fray. The German chemicals giant’s new-ish chief executive, Markus Kamieth, is reportedly considering the future of three divisions — agricultural solutions (pesticides and seeds) coatings (paint for cars) and battery materials. These made perhaps €15.5bn of sales in 2023, out of its total of nearly €70bn, and have been turned into separate legal entities. BASF sold its upstream oil and gas assets to Harbour Energy at the end of last year.

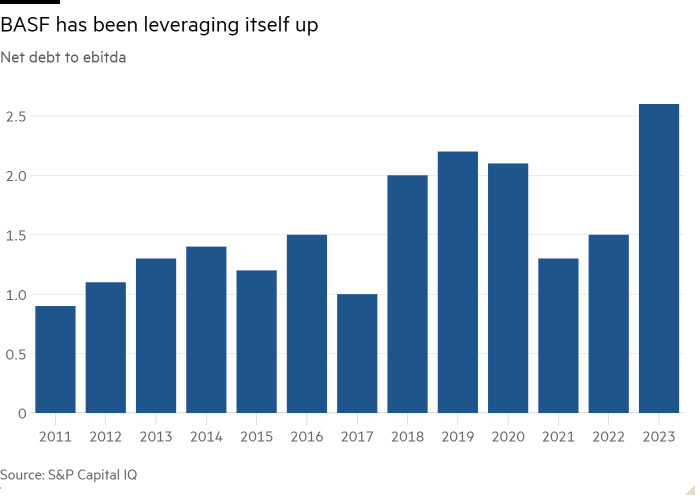

It is easy to see why BASF may be tempted to restructure. High energy prices and hamstrung customers — witness the plight of German auto manufacturers — have hit sales and margins. It will be free cash flow negative after dividend distributions this year and next, thinks Bernstein. The stock is down nearly 30 per cent in the past five years.

The result is that BASF, at €42bn of market capitalisation, is trading on a 20 per cent discount to the sum of its parts, according to Berenberg analysis. It may not be the best time to extract value from agriculture — US farm profitability is forecast to decline — or car coatings, given the travails of the auto sector. But they are big businesses, with an EV of perhaps €25bn between them: setting them loose would help narrow the valuation gap.

Attractive though that might be, however, it would not solve BASF’s underlying strategic problem. Its chemicals division, which turns petroleum products into the base and intermediate molecules needed to make everything else, is seriously challenged. A big chunk of its production is in Europe, where energy prices are a multiple of those of its US and Asian competitors. The unit is in poor shape, with a 3.3 per cent return on capital employed last year, and more than €900mn of negative cash flow. BASF’s restructuring efforts will have to run deeper still.