Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of Martin Sandbu’s Free Lunch newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every Thursday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

The world as we know it is crumbling, we are told — at least the global economy. It is commonplace now to fear a fragmentation of economic links because of geopolitical concerns, protectionism and irreconcilable policy differences on issues from decarbonisation to data privacy.

As we frequently emphasise in Free Lunch, the world is not so much “deglobalising” as dividing into large regional blocs that continue to integrate apace within them. (Hence the finding from the IMF that trade is deepening between geopolitically aligned countries while slowing down between politically distant ones.) The scenario I find most plausible is one where supply chains become more organised around three blocs — centred on China, the EU and the US — but where there is more rather than less cross-border economic activity within each bloc.

Big questions are raised by such a development. Will the US and the EU act as one bloc or two? Is the optimal scale for industries from cars to semiconductors global, or are continental supply chains enough to harness the full economies of scale available? But these are questions about and for the big blocs, even if the answers will affect everyone.

We should, however, also pay attention to the perspective of “in-between” countries: those that do not unavoidably have deeper economic ties to one particular bloc, such as non-EU European countries to the EU, or Mexico and Canada to the US. The in-betweeners include (much like the old non-aligned movement) a large majority of the world’s developing countries. If the global economy fragments into integrated blocs, it would leave a lot of them with a conundrum.

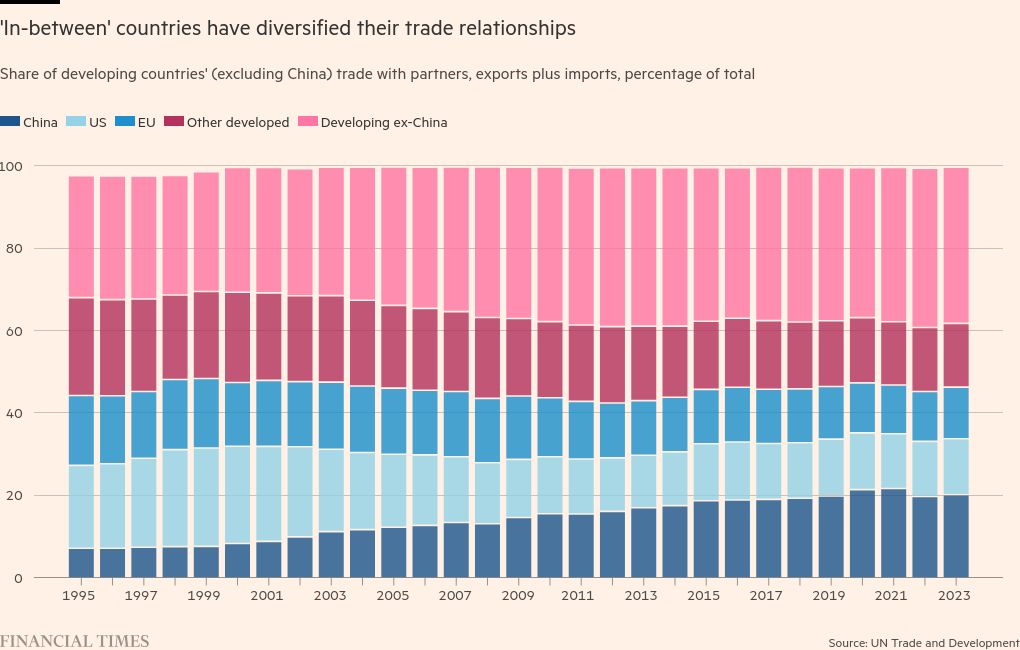

In the past few decades, such countries have largely done well by diversifying their trading relationships. The chart below shows the composition of trade carried out by developing countries other than China, with the large trading blocs mentioned above as well as between themselves.

It is no surprise that China’s share in the in-betweeners’ trade has nearly tripled, while rich countries’ shares have shrunk. (“South-north” trade still accounts for more than 40 per cent of the total, however.) Less often remarked upon is the welcome expansion in trade between developing countries outside of China.

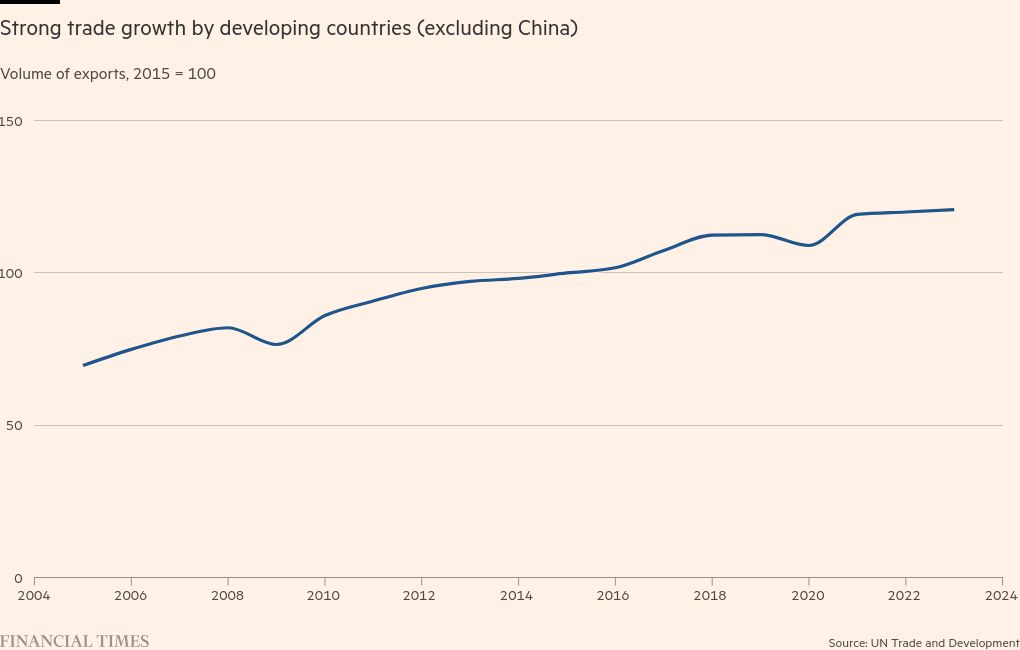

It would be a mistake, however, to think this means the in-betweeners have turned away from their traditional trading partners. The total volume of trade has grown strongly, as the next chart shows:

That absolute growth more than outweighs the shrinking of the rich countries’ share. This, then, is the correct story to tell about global trade in the past few decades: developing countries are trading more with the rich world than they ever have, but they have also added a huge amount of trade with China and each other.

It is a fair simplification to say that everyone is still trading more with everyone than they have at pretty much any time in history — a useful fact to keep in mind when hand-wringing about the end of globalisation. But that also implies a hard choice, if grand politics in the big trading centres points to making it harder and costlier to trade across the blocs. Which will the in-betweeners choose then?

Their sensible preference is not to have to. Hence their effort to stay on good terms with different blocs and their general interest in safeguarding an open, multilateral world economic order, as my colleague Alan Beattie wrote enlighteningly about this week. Beattie’s focus is whether a multilateral approach can prevent “carbon border pricing” from hurting trade, but the same issue arises for all the other motivations that are now making the big blocs warier of each other.

As he points out, however, such efforts at multilateralism are not exactly guaranteed to be successful. And there are early signs that the big trading powers could force in-between countries to make a choice between them. The west is showing a growing appetite for extraterritorial enforcement of its sanctions against Russia, for example. And nobody should feel certain that the US will tolerate the sort of roundabout supply chains where goods previously imported directly from China are now imported via intermediate third countries.

So if push comes to shove, and Latin American, African or Asian trading economies need to cast their lot with one camp or another, what will shape their choices?

Geography will matter, of course. You would need a good reason to choose a more distant trade partner if the cost is to cut yourself off from a closer one. So will resource endowments and comparative advantage. A country blessed with hard-to-come-by raw materials or expertise will find it easier to keep many relationships open.

But the most consequential factors may depend on the politics of the big trading powers. The economic logic for any unaffiliated country to choose the US, the EU or China as a preferred trading partner will depend on the state of the economy of each bloc and the amount of access to it that is offered. There are, of course, also the more direct pecuniary and non-pecuniary inducements: China built its Belt and Road network on offers of cheap (at least in the short term) loans; Ukraine faced invasion when it turned towards the EU and away from a Russia-centred trading area. But in the long term, the promise of gaining prosperity by hewing close to a prosperous economy is going to be the most important determinant of how the global economy divides up.

For many years after the global financial crisis, China was the leader in this regard: its growth easily outshone a crisis-ridden west, and it was willing to shape an economic order centred around it, through policies from Belt and Road to influencing global standard-setting. But it is striking how Beijing’s star is dimming. Hardly a day goes by without new evidence of China’s domestic economic weakness — if you haven’t already, do read my colleagues’ reporting on the country’s dying venture capital market. Many in-betweeners now fear that deep trade relations with China may be too much of a good thing, as a swath of tariff decisions shows. Beijing itself seems less energetic than it once was in trying to draw them into its economic orbit.

A recent Foreign Policy article by James Crabtree explains how this “creates a potential geopolitical opportunity” for the US and Europe. As projects such as the Lobito rail corridor show, western powers are beginning to understand the stakes. But so far, offers such as the EU’s Global Gateway and the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment are too little if not quite too late.

Even so, the US — and especially the EU — start from a better point than one may think. Look back at that first chart: the blocs centred around the big western trading powers are still as weighty as China in the in-betweeners’ trade. Put together, they are much bigger. And while the EU may not have the US’s dynamism — that is what the recent Mario Draghi report hopes to remedy — the EU has the potential to offer much more market access than one can hope from the increasingly inward-looking US. But that requires making the strategic choice of offering ways for even far-flung countries to associate with the EU, which in turn requires the sort of “foreign economic policy” Draghi calls for.

Other readables

Recommended newsletters for you

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Your essential guide to money, interest rates, inflation and what central banks are thinking. Sign up here

Unhedged — Robert Armstrong dissects the most important market trends and discusses how Wall Street’s best minds respond to them. Sign up here