London has been building passenger railways since the 1830s when steam locomotives started hauling commuters into the city.

But the building boom has stalled, and for the first time in about 20 years no large public transport projects are being constructed, as London’s transport authority grapples with uncertainty over its finances and how people will travel in the future. The only building work is for the beleaguered HS2 rail link, which is an inter-city service and is not designed to improve transport within London.

Sadiq Khan, the city’s mayor and chair of Transport for London, has a £50bn list of unfunded projects he believes are needed to unlock development and regenerate neighbourhoods that have been historically underserved by the rail and London Underground networks.

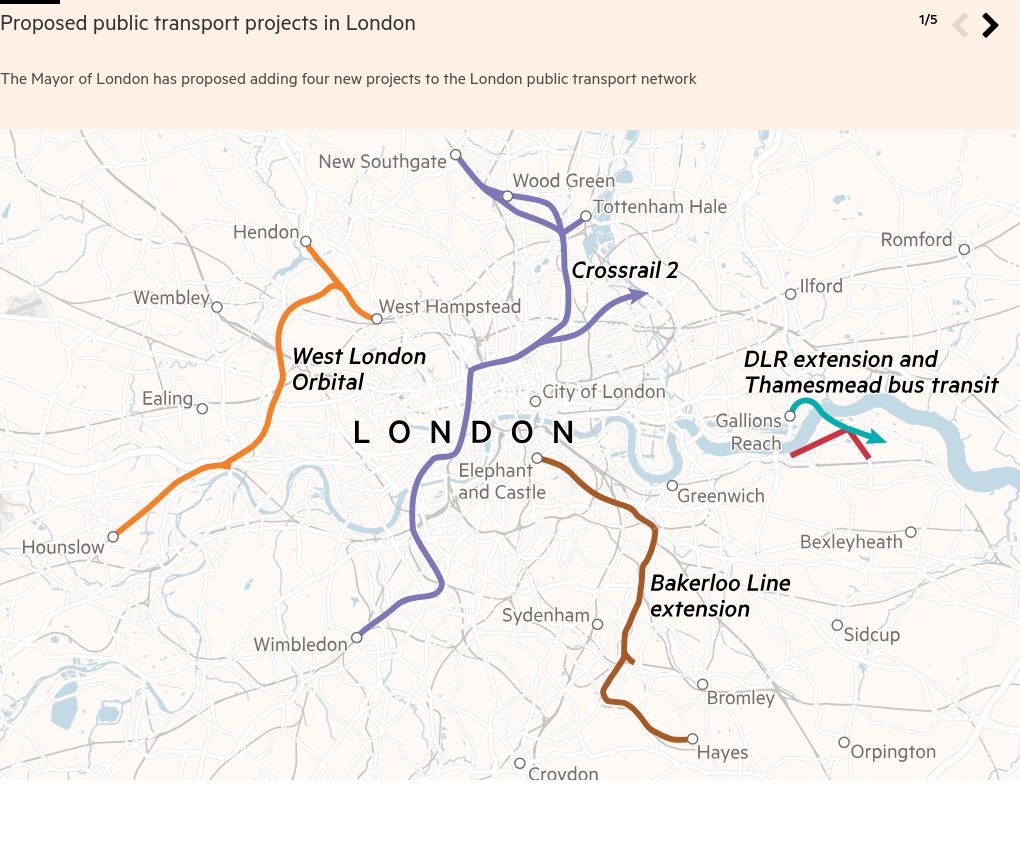

The four main projects include expansions of existing lines: extending the Bakerloo Underground line further into south London and the driverless Docklands Light Railway into new parts of east London. There is also a proposal to connect old and underused rail lines in west London to form a new orbital line linking suburbs in the west of the city.

There is a longer-term ambition to spend tens of billions of pounds digging a new north to south “Crossrail 2” railway underneath London as a successor to the east to west Crossrail, or Elizabeth Line, which opened in 2022.

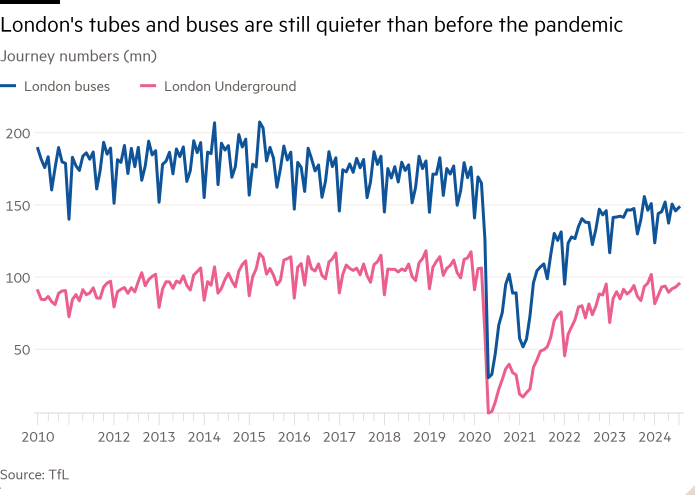

But TfL cannot afford to build anything without more cash from central government, after its finances were shredded by a collapse in the number of people travelling during the pandemic.

Its struggles have raised questions over how London will respond to a growing population, the need to build more houses and to meet net zero targets.

“A world class city needs a world class transport system,” said Sir John Armitt, who chaired the London Olympic Delivery Authority and has run both Network Rail and the company that built the high-speed rail line to the Channel Tunnel.

Now chair of the National Infrastructure Commission, he said the Elizabeth Line “can’t be the end of the line for new capacity”.

Building new railways in London has always happened erratically. The core of the Underground network in central London was completed in less than 50 years around the turn of the 20th century. But just two new lines were added over the next 100 years.

The start of the 21st century saw rapid development as power over transport policy was devolved to local government in London. The London Overground, Thameslink and Elizabeth Line rail networks were all built, while the Northern Line on the London Underground was extended to Battersea Power station.

John Dickie, chief executive at lobby group BusinessLDN, said Londoners have forgotten what it feels like to have a transport network suffering from under-investment.

“People sort of forget in the 1990s people would go to meetings late or not go to work because of transport problems. An awful lot of time and effort went into improving the system, which has not finished,” he said.

Tony Travers, professor of local government at the London School of Economics, agreed that London “needs to keep investing in its transport infrastructure as other cities such as Paris are improving their systems”.

To begin building, Khan will need to persuade the new Labour government, his political allies, to hand cash to a city that has historically enjoyed good transport links, and is better connected than any other in the UK. He will also need to overcome the UK’s poor record at building infrastructure on time and on budget.

Khan is “hugely excited about the reset in the relationship between London and the national government”, a spokesperson said. The mayor expects to “work hand-in-hand with the new transport secretary to deliver a better London for everyone and the change the country needs”, they added.

Local politicians and business leaders are pushing the government for a long-term funding agreement for TfL, after it spent four years muddling through six short-term bailouts from the previous Conservative administration.

“It is of extraordinary fundamental importance to business . . . as a city changes then transport has to change with it,” said Dickie.

London is not alone. Public transport operators around the world are facing a crunch after the pandemic hit passenger revenue and accelerated a shift to homeworking, which has undermined the logic of building mass transit systems to ferry workers into cities.

Stephen Glaister, emeritus professor of transport policy at Imperial College London, said the economic justification for some proposed projects might have lessened given the downturn in passenger numbers, particularly on Mondays and Fridays.

Another issue is the sharply rising cost of engineering works such as digging tunnels, said Glaister.

Although there has been substantial planning work on Crossrail 2, which would run between Wimbledon in south-west London to Tottenham Hale in north London and beyond, the project was canned under the last government as it prioritised “levelling up” projects in the north.

While arguing that the underground railway — costed at up to £40bn in 2021 — will be needed one day, Khan is focusing on cheaper and quicker projects — the extensions to the Bakerloo Line and DLR, and creation of the West London Orbital Railway — which could also be at least partly funded by the private sector.

He argues that new transport projects are needed to stimulate housebuilding and regenerate parts of London.

TfL has estimated that its four proposed projects could collectively unlock up to 300,000 new homes, including a large development east of the Canary Wharf financial district that has been dubbed “Docklands 2.0”, a nod to the regeneration of the Port of London in the 1980s.

“For the last 10 years TfL has seen its job not simply as a conventional transit authority,” BusinessLDN’s Dickie said. “It has started to think in particular what transport connectivity could do to the capacity of London to build more homes.”

Although the projects would be difficult to deliver using private finance alone, the government could seek to use some of the increased value of stations and retail developments built nearby to contribute to funding.

The Northern Line extension to Battersea power station in central London, completed in 2021, was partly paid for by a levy on developers as well as by allowing local tax in the surrounding area to be captured to repay the project’s debt.

A significant proportion of funding for the original Crossrail project also came from a levy on the business rates in the area and from borrowing against future income.

Dickie said the Crossrail project had shown there is room to squeeze more money out of the private sector to fund new infrastructure. This could include higher taxes on housing development or the sale of existing houses near new stations, he said, or “more targeted” business rate rises around stations.

But, he added, that could never be a substitute for central government cash.

“TfL needs a long-term funding settlement to help it plan for the future, with enhancements that ensure London can remain competitive with other capitals across the world,” Armitt said.

And while south Londoners hope the Bakerloo tube line will one day reach them, Khan has offered the best he can afford as an interim solution: a “Bakerloop” bus, which would follow the route of the long-awaited Underground extension.