Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Cost of living crisis myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

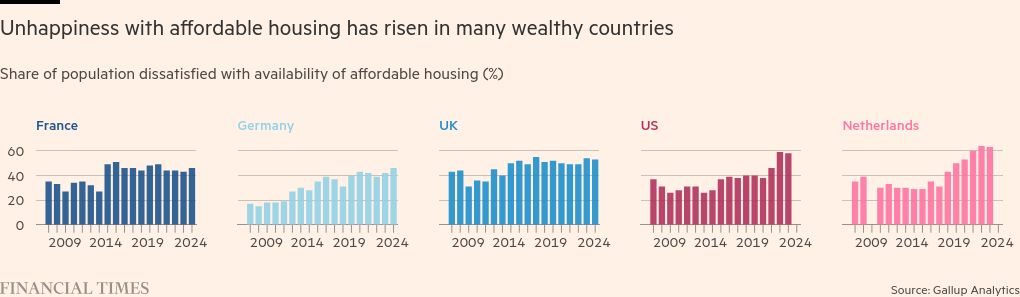

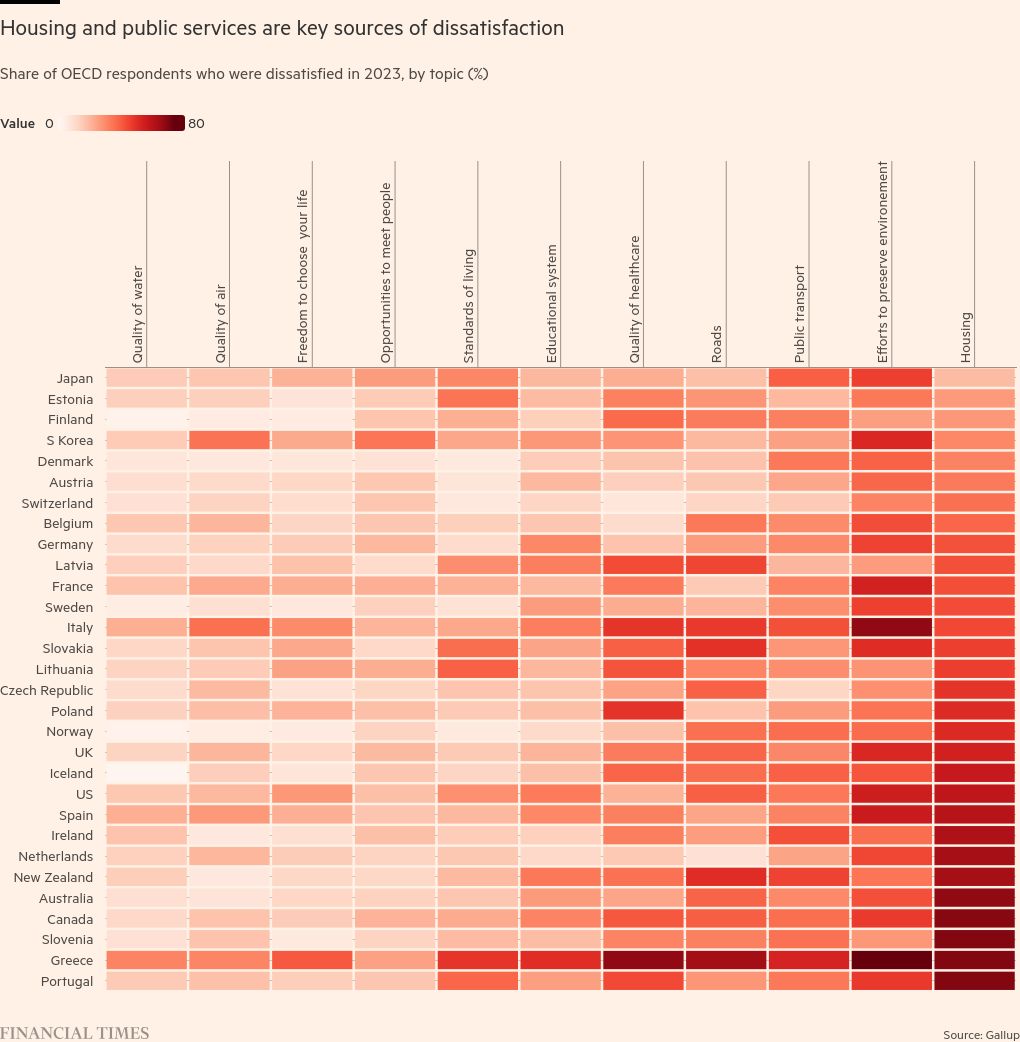

Dissatisfaction with housing costs has hit a record high across rich countries, soaring above other worries such as healthcare and education.

Half of respondents in OECD nations are dissatisfied with the availability of affordable housing, according to Gallup Analytics figures, a sharp rise since central banks hiked interest rates to deal with the worst bout of inflation in a generation.

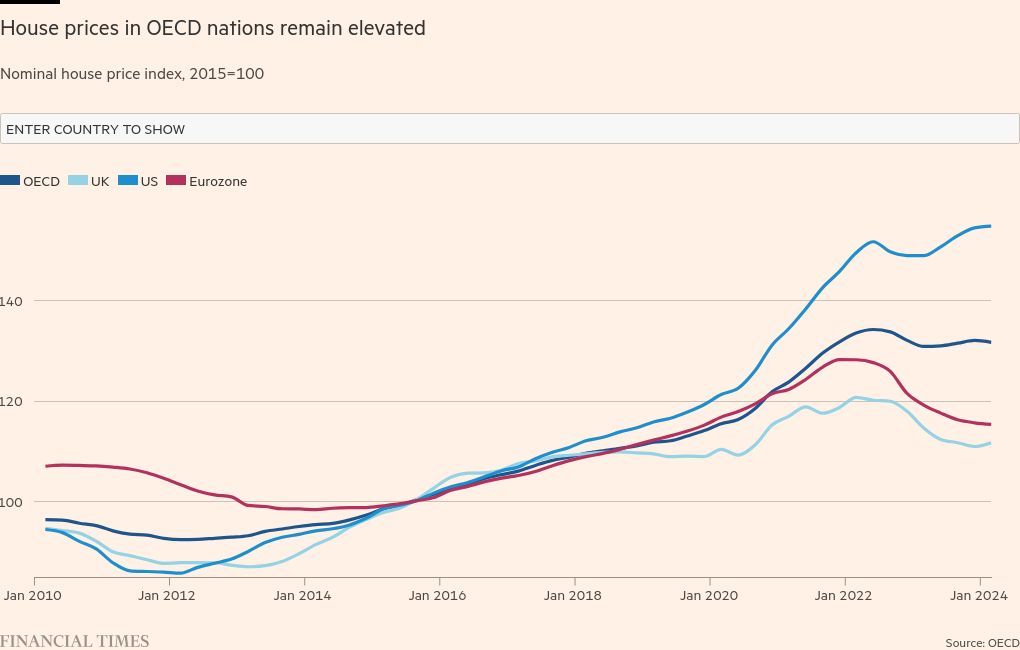

While higher rates have helped bring down property prices in several European countries, housing remains more expensive than before the pandemic — even before factoring in higher borrowing costs.

In the US, house prices have soared despite rises in interest rates. Almost 60 per cent of those polled in the world’s largest economy said they were dissatisfied with the stock of affordable housing.

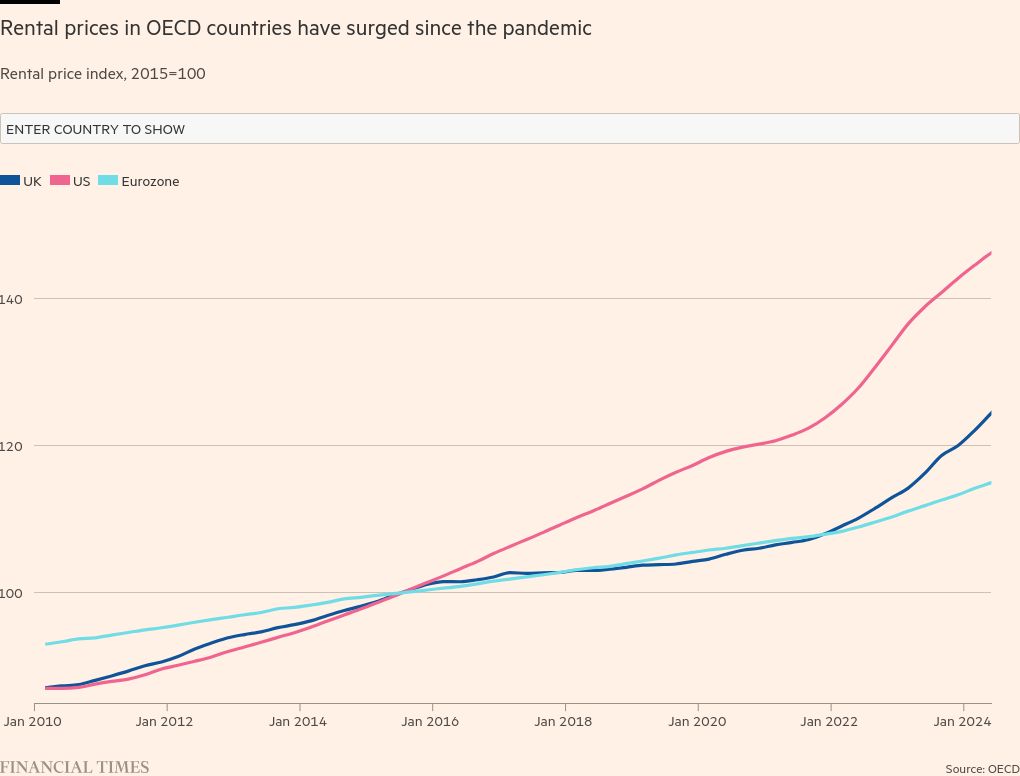

Rents, meanwhile, have surged at a time when higher prices for other essentials, such as food and fuel, have been cutting into disposable incomes.

Researchers partly blame a lack of construction of new homes for the affordability crisis.

“Basically we haven’t built enough,” said Willem Adema, a senior economist in the social policy division of the OECD, adding that developers were often targeting wealthier households, exacerbating the strain on those on lower incomes.

Andrew Wishart, an analyst at Capital Economics, said: “Population trends can move much faster than you can change housing supply.”

Discontent over housing is set to play an important role in elections this year, notably in the US, where voters head to the polls in November.

The average house price is now almost 38 per cent higher than when US President Joe Biden took office in January 2021, according to the Case-Shiller index.

Research by Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies showed the monthly housing payment on a median-priced home with a low-deposit loan, as favoured by first-time buyers, was now $3,096 — compared with around $2,000 in January 2021.

Meanwhile, many existing homeowners have locked in 30-year mortgages at ultra-low rates, and as a whole are paying less on servicing debt as a percentage of income than at any time since 1980, according to Harvard.

The Gallup data, based on responses from more than 37,000 people in the 37 countries that make up the OECD’s club of wealthy states, show that discontent over housing affordability is highest among under-30s and those aged 30 to 49, many of whom may be trying to get on the property ladder.

Some 44 per cent of over-50s were dissatisfied with housing across the OECD countries, but the proportion rose to 55 per cent for the under-30s and 56 per cent for those aged 30 to 49.

In England, house prices are now eight times the average annual wage, according to official statistics. That is more than twice the ratio seen when the last Labour government took office in 1997. The number of households living in temporary accommodation in England is also at a record high.

About 30 per cent of the population in rich countries were dissatisfied with the healthcare system, education and public transport. Unhappiness with the standard of living increased in 2023, but only slightly, rising from 24 to 25 per cent.

The Gallup World Poll is compiled annually, with the 2023 survey based on responses from 145,702 people in 142 countries and weighted according to population. Respondents are asked about a range of socio-economic and political issues.

Some countries where 2024 data is already available have shown a further increase in dissatisfaction with housing this year. In Germany, the share of those unhappy about the availability of affordable housing rose to a new high of 46 per cent, up from 42 per cent in 2023 and more than double the levels up to 2012. In Spain, the share of those dissatisfied with housing rose to 62 per cent in 2024, the highest since the financial crisis.

Additional reporting by Janina Conboye in London