This First Person column is written by Hassan Yahaya, who lives in Edmonton. For more information about First Person stories, see the FAQ.

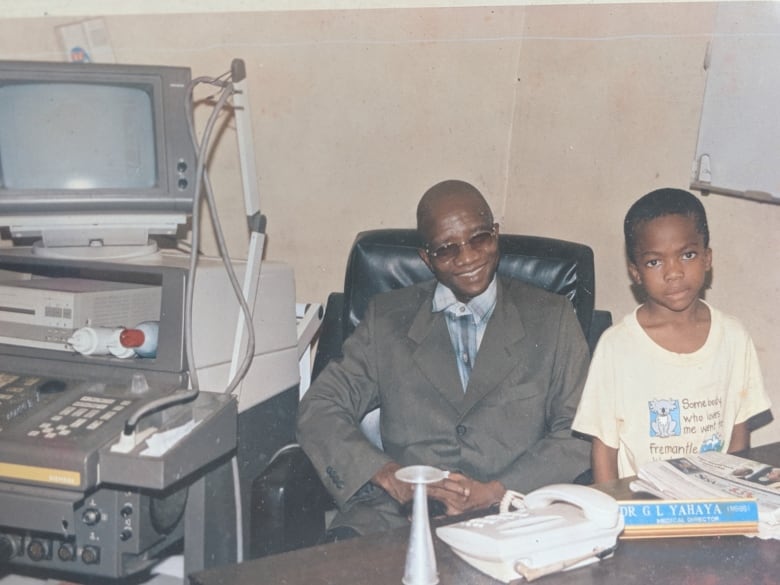

As a child growing up in Lagos, Nigeria, the most common statement I heard from family and friends was, “You look just like your dad.”

Puzzled, I would spend hours staring into the mirror, trying — and failing — to see what they saw. Was it the eyes? Or the shape of our ears? Perhaps the nose? Or the way we smiled?

I could never figure it out.

With time, the comments became so overwhelming that I decided they must be true. So, I tried to become the perfect copy of my dad. I’d try on his work clothes to see how they fit, imitate his deep bass voice to feel the power of his words and generally mirror his behaviours to imagine a future version of myself.

Quickly, family and friends noticed these changes. They moved from, “You look just like him” to “You behave just like him.”

It was a source of pride when people would say, “You’re independent, just like your dad.” I admired this trait in him, and his favourite statement — “No one is coming to save you”— reinforced it.

This was a reminder that even with my home country of Nigeria’s communal structure, everyone competes for scarce resources. Even though extended family members support each other, the dire economic situation guarantees that — sooner rather than later — the instinct for self-preservation trumps any form of unbridled generosity.

So, I inherited my dad’s self-sufficient spirit and lived like that for a long time. That’s why I didn’t think to ask for financial or other help when I rented my first apartment in Nigeria. It’s also why I was perfectly fine driving myself, while in extreme discomfort, to the hospital during a serious bout of illness. In my head, I had to be independent, just like my dad constantly preached.

Then, on the 18th of April, 2024, I moved to Canada in search of better work opportunities.

A new me

My first thought at the Edmonton airport was, “Everything seems so different,” and I had a nagging suspicion that things were about to change. In some parts of my mind, I knew I was about to relearn everything I knew about life and myself in this new cultural landscape.

The first signs were small ones. During the initial phase of acquiring documentation, I’d stammer when asked questions like, “What’s your house address and postal code?” or pause when someone asked for my Canadian phone number.

Thankfully, my friends from back home who had moved to Canada before me were a text away, volunteering the answers and mildly scolding me for constantly apologizing for “disturbing them.”

Before coming to Canada, I rented an apartment in Edmonton because I didn’t want to burden my friends. But because of my flight schedule, I couldn’t pick up the keys until the day after I landed. My closest friends immediately offered my partner and me their apartment without blinking. That night, they slept on the couch while we slept peacefully in their bed. Their generosity and selflessness made me feel like I mattered; that in a world of seven billion people, I was more than a statistical rounding error. And in that moment, I felt warm, safe, and less alone in a great, big world.

On our first morning in Canada, another friend cleared her schedule to drive us to get our social insurance numbers and open bank accounts. Her answer to my constant questions, such as “Are you sure you can take time off work to do this?” and “Sorry for stressing you,” was a soft smile, followed by, “It’s fine.”

Back home, my partner and I agreed to buy only the most essential things — like a bed, work table, and chairs — for the apartment and add more only after getting jobs in Canada. After all, no one was coming to save us.

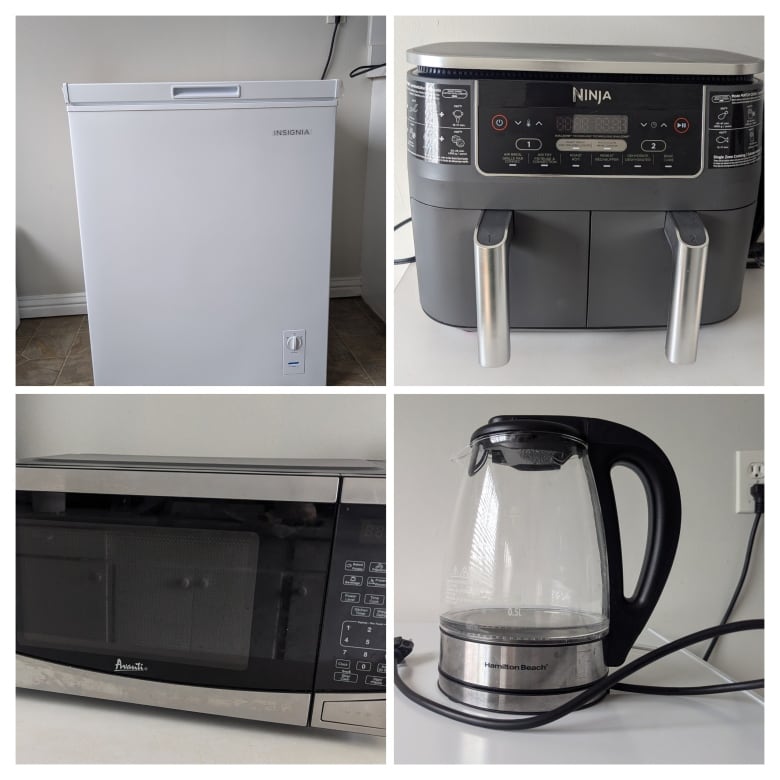

Imagine our surprise when one friend bought a set of pots for our kitchen. Before we could take it in, another friend got us a freezer and a microwave. Someone else bought us a blender. Still processing the kindness, we got an electric kettle and a big gallon of oil. Other friends, independent of each other, started sending money, food, prayers, contacts to reach out to for a job and positive vibes our way.

It felt strange to receive so much help. Even stranger, was that contrary to my self-sufficient mindset, so many people in our Nigerian community were happy to help.

At different times, I’ve asked my friends why they are so kind, and everyone says it’s because of the communal spirit from back home. But I have an additional theory. Besides the difficulty of migration, not having to compete (too much) for scarce resources allows everyone to become the best version of themselves.

Yusuf Shire works evenings and weekends volunteering for the New Brunswick African Association

Whatever the answer is, it doesn’t matter in the grand scheme. All that matters is that it took being 10,000 kilometres away from home to learn that it’s OK to ask for and receive help.

At the end of the day I learned the meaning of the African proverb: umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu — a person is a person because of other people, and I’m deeply grateful for that lesson.

Do you have a compelling personal story that can bring understanding or help others? We want to hear from you. Here’s more info on how to pitch to us.

For more stories about the experiences of Black Canadians — from features on anti-Black racism to success stories from within the Black community — check out Being Black in Canada, a CBC project Black Canadians can be proud of. You can read more stories here.