Two of Israel’s greatest enemies were killed this week within a period of hours, as assassinations took the lives of the senior figures in regional militant groups who played key, but very different roles in the Jewish state’s long conflict with its neighbours.

The first, Fuad Shukr, operated in the shadows. He was one of the earliest members of Hizbollah, the Shia militant group created in the 1980s during Lebanon’s civil war and Israel’s subsequent invasion. Shukr was also the supposed architect of some of the region’s most destabilising events, including the 1983 bombing of a US marine barracks, and helped Hizbollah evolve from a small guerrilla group to a battle-hardened paramilitary force.

The second, Ismail Haniyeh, lived openly and at large as the political chief of the Sunni group Hamas, after rising to power in the chaos of the second intifada, or uprising, in the occupied Palestinian territories. In recent years he jetted around Middle Eastern capitals as Hamas’s top international envoy, maintaining ties from Turkey to Iran, while living in a villa in Doha.

Israel has claimed responsibility for Shukr’s death, saying it came in retaliation for the killing by a suspected Hizbollah rocket last weekend of 12 children and teenagers playing football in the occupied Golan Heights.

It has yet to claim Haniyeh’s death, in line with its policy of rarely taking responsibility for assassinations or sabotage in Iran, where the Hamas leader had just travelled for the new president’s inauguration. Both Hamas and Iran blamed Israel for Haniyeh’s killing, which local news reports suggested involved an air strike at his residence.

Shukr’s killing leaves a significant hole in Hizbollah’s senior leadership, since Israel “killed the main guy in charge of all Hizbollah military planning and readiness”, said Emile Hokayem, director of regional security at the International Institute for Strategic Studies. “If there’s one person Israel wanted to remove at the top, who was a real strategic and operational heavyweight, it was him.”

But Haniyeh’s killing risks the failure of the already-stalled indirect negotiations between Israel and Hamas to swap Israeli hostages for Palestinian prisoners, and agree a ceasefire to halt nine months of war in Gaza.

“He was one of the ones pushing for a deal and compromise, and because of his stature he was able to speak to the guys in Gaza in a more convincing way than other guys,” said one Arab diplomat.

While there were others from Hamas involved in the negotiations, “you’ve lost a big voice who was influential and could have a strong say internally within Hamas and was for a deal”.

Indeed, the Qatari Prime Minister Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman al-Thani warned that Haniyeh’s killing would only endanger the talks. “How can mediation succeed when one party assassinates the negotiator on other side?” he said on X.

Taken together, the two killings are an escalation of the hostilities and a warning to Israel’s foes. They display both military and intelligence capabilities designed to embarrass Israel’s enemies, and political intent to eliminate important senior leaders. Haniyeh in particular had become a household name in Israel, mocked on television satire shows for a lavish lifestyle, and hated by the government for his life of freedom and safety in Qatar.

Haniyeh, a thorn in Israel’s side for decades, ascended the ranks of Hamas partly through his intimate relationship as personal assistant to its founder, the quadriplegic Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, and partly through circumstance. Between 2002 and 2005, Israel assassinated five of the men closest to Yassin, and finally Yassin himself. That left Haniyeh to inherit the mantle of its political leadership.

Round-faced and smiling, Haniyeh had become increasingly ubiquitous in Yassin’s inner circle during the late 1990s and early 2000s — feeding him, holding the phone to his ear, flipping channels on the television and pushing his wheelchair around Gaza.

He was born in 1961 in Gaza to parents who were made refugees in the 1948 war that created Israel, After studying Arabic literature at the Islamic University of Gaza, he joined Hamas soon after it was founded in 1987, working his way through its early, informal power structure to Yassin’s side. One western diplomat who met Haniyeh in the early 1990s described him as “a permanent limb to the angry Sheikh”.

The fact that Yassin, a target of Israeli assassination attempts, trusted him with such intimate confidences gave him a natural patina of spiritual purity in Islamist circles, said a person who frequently met him during those early days of his ascent to Hamas’s leadership.

“He was the voice of the Sheikh [Yassin],” said the person, who now lives in exile. “He was the dutiful son, but not the natural heir — there were many others who had to die before he got his chance.”

That chance came in 2006, when Haniyeh led Hamas to victory over Fatah, its more secular, West Bank-based rival, in US-backed elections in the Palestinian territories.

After the US, EU and Israel denied Haniyeh the chance to lead as prime minister, his military colleagues in Hamas ousted Fatah from the Gaza Strip in a violent coup. In a parting shot, Fatah fighters fired a rocket-propelled grenade into Haniyeh’s home on the Mediterranean seafront of the Shati refugee camp. (On Wednesday, the Fatah leader and Haniyeh’s arch-rival, Mahmoud Abbas, declared a day of national mourning to mark his killing.)

During this period of transition in Gaza, Haniyeh had swapped his prayer caps and white robes for formal suits and starched white shirts, delivering a weekly sermon in a quiet voice that diplomats and journalists scoured for signals of where Hamas was headed.

He fended off rivals, including Khaled Mashal, who had taken over Hamas’s politburo after Haniyeh’s mentor, Yassin, was assassinated by Israel in 2004.

In the fractious local politics of Gaza, Haniyeh was soon to be eclipsed by Yahya Sinwar, the man Israel holds directly responsible for the October 7 attacks. Sinwar won a 2017 internal vote to run Gaza for Hamas, while Haniyeh was selected a few months later to run the group’s political policies, moving to Doha to nurture its international alliances.

He cultivated ties with Turkey and Qatar, which are sympathetic to its Muslim Brotherhood-inspired ideology, and with Iran, which has increasingly provided military assistance.

In the past few months, since Hamas’s October 7 attack on Israel that triggered the war in Gaza, Israel has destroyed his house in Shati using bulldozers, tank shells and air strikes.

It killed his three sons in an April assault, saying they were about to launch an attack on Israeli troops; Haniyeh also lost four grandchildren in the same air strike. His sister and her family were killed two months later in another Israeli air strike in Gaza.

“All our people and all the families of Gaza have paid a heavy price in blood, and I am one of them,” Haniyeh said at the time.

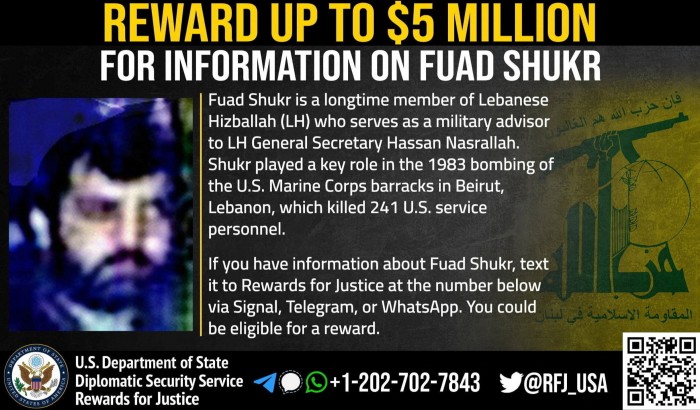

Compared with Haniyeh, little is known about Shukr, a militant that Israel has called Hizbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah’s “right-hand man”. He was so inconspicuous that even his rank in the armed group remains difficult to pin down.

What is clear, however, is that he was a significant player in the Iran-backed organisation, one who helped lead its combat operations and sat on the group’s highest military body, the Jihad Council, along with Nasrallah and a handful of his most trusted advisers.

Shukr was one of the original members of the fledgling militant group, part of a generation of men who helped transform the organisation from a motley of insurgents in the early 1980s, to one of the world’s most powerful non-state military forces.

Two people with knowledge of the group’s operations said his status was akin to that of Imad Mughniyeh — a highly revered Hizbollah military commander who was assassinated in Syria in 2008, a killing widely blamed on Israel and the CIA — and his brother-in-law Mustafa Badreddine, who was killed in Syria in 2016. Shukr is known to have been close to both men.

Following Badreddine’s death, Shukr was reportedly tapped to take on one of the highest military roles in Hizbollah. He was soon instrumental in helping Hizbollah fighters and assorted pro-Assad forces defeat opposition forces during Syria’s civil war, those people said.

Shukr, who also went by Sayyed or Hajj Mohsen, was believed to be in his early 60s and was born in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley.

The US placed Shukr on its specially designated terrorist list in 2019, and offered a $5mn reward for information, accusing him of playing a leading role in the 1983 bombing of the US marine barracks in Beirut that killed 241 US military personnel.