Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the US & Canadian companies myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Ashley Nunes is a research associate at Harvard Law School and teaches economic policy at Harvard College.

Uber and Lyft drivers are contractors, not employees. That’s the verdict from California’s top court, ending a bitter, yearslong dispute between ride-hailing workers and the apps that employ them.

Uber was naturally triumphant after last week’s ruling from the California Supreme Court that upheld Proposition 22, the state law that made app workers “independent contractors” rather than employees:

Whether drivers or couriers choose to earn just a few hours a week or more, their freedom to work when and how they want is now firmly etched into California law, putting an end to misguided attempts to force them into an employment model that they overwhelmingly do not want.

Moving forward, Uber and Lyft drivers across the state should expect little change in their working conditions, something Uber gleefully says is, “a testament to what can be done when we listen to drivers and couriers.” Predictably, worker advocacy groups don’t share that sentiment.

As the SEIU-backed plaintiff — Uber and Lyft driver Hector Castellanos — said in a statement:

Over the last three years, gig workers across California have experienced firsthand that Prop 22 is nothing more than a bait-and-switch meant to enrich global corporations at the expense of the Black, brown and immigrant workers who power their earnings. Prop 22 has allowed gig companies like Uber, Lyft and DoorDash to deprive us of a living wage, access to workers compensation, paid sick leave and meaningful health care coverage.

Drivers are crucial to companies like Uber. The ride-hailing industry’s signature feature — mobility on demand — depends on driver “inventory”: an armada of drivers that can be summoned at a moment’s notice. But it the business model depends on treating those drivers as contractors, not employees.

The distinction matters because of, well, cash. Contractors are cheap; employees, less so. Contractors can be denied everything from a minimum wage guarantee to unemployment insurance to healthcare. Do that with employees and you’re asking for trouble.

Which explains why ride-hailing companies have long treated drivers as contractors, and why they are loath to change course. Do so and costs could rise. And rise they almost certainly would. In California, a crucial market for the ride-hailing industry, Barclays has pegged the cost of reclassifying workers at $3,625 per driver.

Multiply that by the over 150,000 plus drivers Uber alone has in the state and you’re talking about serious money (it doesn’t help that ride-hailing companies have already lost billions). So their stance is understandable. But it is indicative of a business model whose success requires skirting the spirit of labour laws.

That’s not how companies like Uber see it, of course. Instead, they tout the virtues of flexibility; a modus operandi that can best be summed up as “drive for us and we’ll let you work where you want, when you want.” It’s nice to work as you please. But it’s also nice to know how much you’re making when you do work.

And this is the real problem. Skimping on employee perks is one thing. Plenty of employers do that — bars, pubs and restaurants come to mind. But those employers are upfront about what employees get paid. How much cash ride-hailing drivers actually make is tricky to nail down.

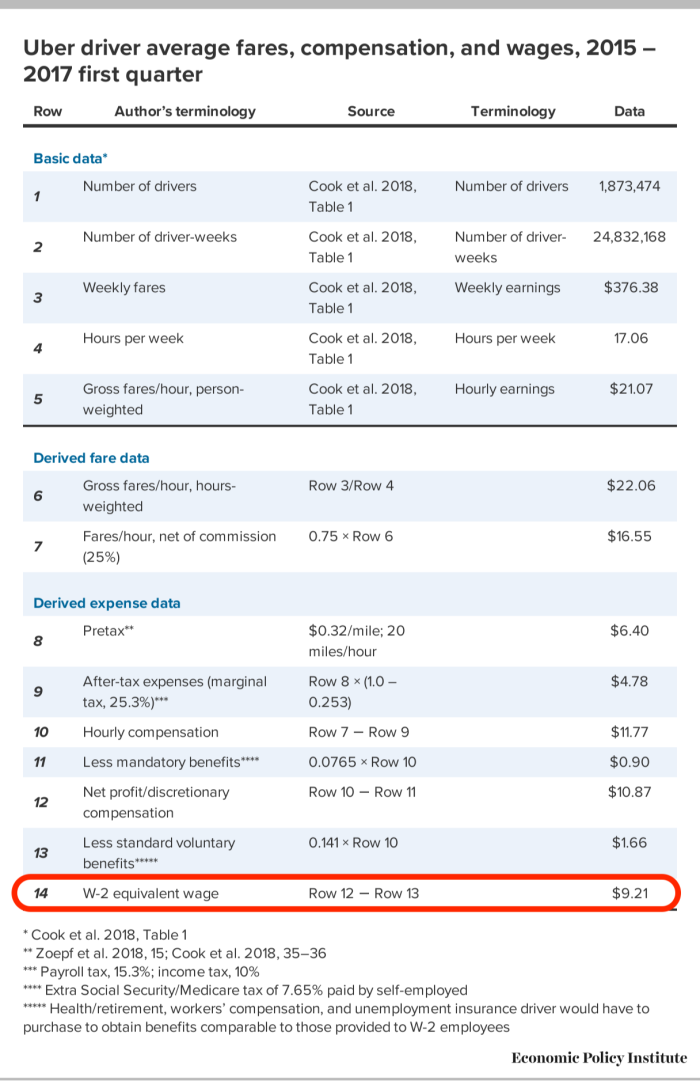

Uber has previously said its drivers earn upwards of $20 an hour. Not too shabby in theory, but there’s a difference between earnings and wages. Uber’s numbers don’t adjust for expenses — everything from gasoline to insurance to most importantly, hefty, hidden add-on fees drivers are charged for using the Uber platform. Once those costs are factored in, things change.

Some estimates peg a driver’s true hourly wage at around $16. Others say it’s less. All show drivers make less than the $32 private-sector workers earn on average, and some estimates suggest wages may dip below the minimum wage in several major US cities including Chicago, New York, and San Francisco all of which are important markets for ride-hailing companies.

Here are the estimates from a 2018 Economic Policy Institute report on the subject:

The likes of Uber vociferously dispute these figures of course. Yet, they won’t definitively say — one way or the other — how much their drivers actually make.

Just to be clear, this is not an argument that rail-hailing drivers should necessarily make more money. It’s unclear what economic value these drivers bring to the market beyond knowing how to drive. What they do have is the initial belief that driving for companies like Uber may be more lucrative than it really is. Which probably explains why so many drivers quit within months of starting.

The solution to this isn’t more perks or higher wages; it is pay transparency. Ride-hailing companies should clearly and publicly disclose what drivers really make. The fact that estimates for how much they earn are all over the map shows just how opaque things are.

The likes of Uber and Lyft should eliminate hidden fees, commissions and charges that drivers are forced to pony up, and instead embrace an upfront pricing model. Then drivers at least know what they’re getting into.

The result may well be drivers fleeing in droves. Trading a minimum wage guarantee for “flexibility” is hardly an appealing prospect. But that’s a trade-off some drivers may — and should — be allowed to make. We just shouldn’t force others into following suit.