Jay Newman was a portfolio manager at Elliott Management. Management. John-David Seelig is a data scientist at Rose Technology. Alexander Campbell was an investor at Bridgewater Associates and is the CEO of Rose Technology,

Sovereign defaults, like happy families, are more alike than not. They are passion plays where each cast members have obvious but conflicting goals. To wit:

Sovereign debtors: incumbent politicians — rarely the same (often corrupt) people who borrowed the money in the first place — want to placate their people and the official sector by paying as little and as late as possible.

Creditors — rarely the same people who bought bonds in the first place — want to be paid as much as possible, as soon as possible. Most important: they want terms that ensure inclusion in emerging market indices so that the new bonds look sexy enough to pump prices and dump paper.

The official sector, exemplified by the IMF, doesn’t even pretend to be an impartial arbiter. Always takes the debtors’ side, to ensure that its own politically-driven loans are paid in full.

The Chinese: true entrepreneurs and innovators in the world of predatory sovereign investment and lending. After making questionable loans for shoddy Belt & Road projects, they work tirelessly to get paid in cash or in kind. In full. No matter what.

The entire cast is on stage for the play du jour: Sri Lanka. Having first struck a deal with some of its sovereign creditors ($6bn of Chinese claims still to go), Sri Lanka has now secured a restructuring agreement with bondholders representing $13bn of external debt. Bondholders have offered to lop off a big chunk of principal in exchange for a “macro”-linked kicker based on how the economy performs.

As ever, creditors are playing catch-up — trying to recoup some of their losses. GDP-kickers are just the latest unworkable idea in service of an attempt to manage the bigger problem of imprudent lending and borrowing. In the bizarro universe of developing country debt, bad ideas thrive.

As Argentina enters the sixth year of court battles over its version of GDP-linkers — winning in the UK but losing in the U.S — unwarranted enthusiasm persists. As FTAV observed earlier this year:

Over the years the International Monetary Fund, the Federal Reserve, the Reserve Bank of Australia, the Banque de France, the Bank of England and the Bank of Canada and the United Nations have all come out in favour of some variant.

It’s not that linkers are an inherently dumb concept. As ideas go, this one is simple: if a debtor does well, creditors who forego payments today should get paid more tomorrow. It is mathematically elegant and linguistically ineluctable.

But, except as a fig leaf for governments that want to seem market-friendly, they just don’t work.

GDP-linkage seems attractive because it’s an abstraction. But its disparate elements are susceptible to direct and indirect government influence, as the evergreen dispute arising from GDP-linked bonds issued by Argentina in 2005 suggests. In reality, GDP-linked features provide little protection to creditors, but offer debtors another opportunity to game restructurings.

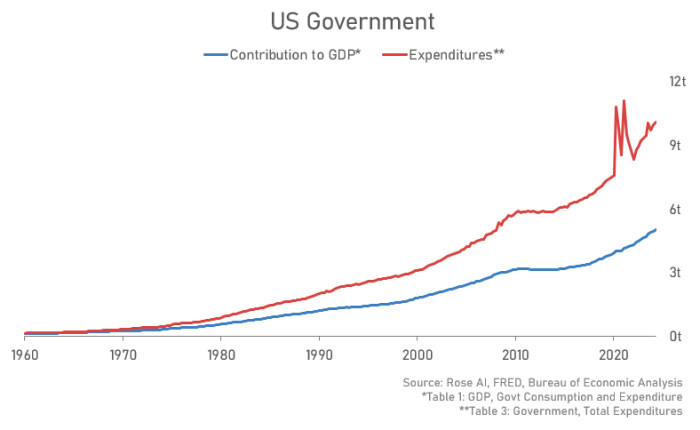

The components of GDP are all influenced by government policies. And, sometimes for legitimate reasons, governments revise metrics, ostensibly to account for changing data sources, methodological enhancements, and shifting economic goals. Fiscal and foreign policies directly affect components of GDP, and GDP is most easily boosted through spending — even though a dollar of spending rarely results in an equivalent increase in GDP.

In addition to internal economics, how trade is reported can have a direct impact on nominal GDP. To protect against money printing or artificial devaluation, investors might seek to tie exchange rates to economic reality. Bonds are typically issued in an independent currency, however another method is to adjust GDP to local inflation via a GDP deflator.

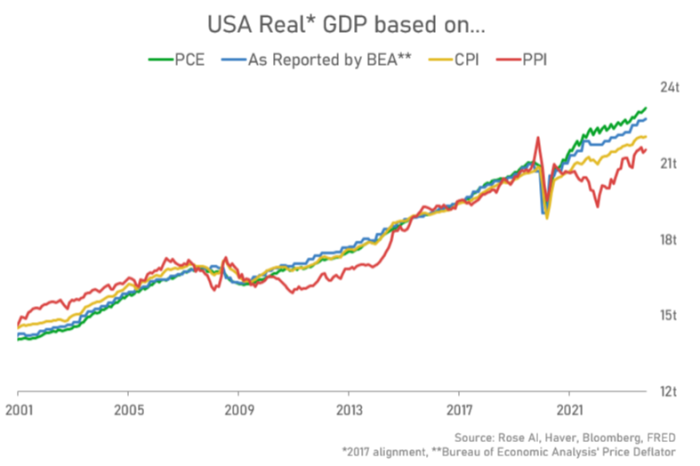

The selection of this deflator can produce dramatically different results, even in advanced economies like the US.

Compounding the opportunity for moral hazard, governments frequently reweight and revise the calculation and methodologies of inflation deflators. An alternative to making the inflation calculation might be to rely on foreign exchange rates — also not a perfect fix, since they’re affected by geopolitics (eg: Russia’s various incursions into Ukraine).

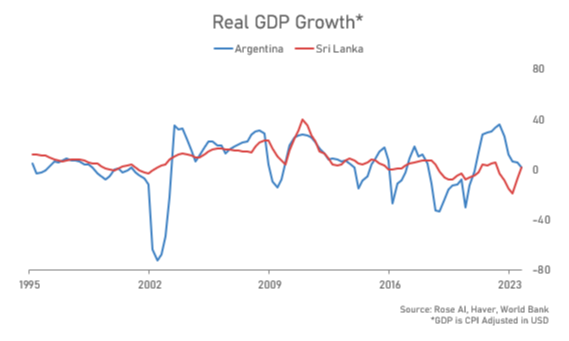

Both these options can be extremely volatile. In the Argentine case, exchange rates and inflation deflators would have produced vastly different returns on GDP linked instruments depending on the exact month.

Returning to Sri Lanka: the country has slowed significantly over the past couple of years, while adding new debt. The current leaders are full of promises, but the institutions are untested.

Argentina, perennially, reveals the hazards. Volatility arises not only from geopolitical factors that influence growth, but economic mismanagement, and largely unconstrained internal and external debt issuance: even before the ever-present risk of malicious government intervention.

No matter. The lessons taught by Argentina about the inherent fragility of macro-features won’t be learned. The Sri Lankans will adopt some form of GDP-linkage. After that, they’ll find their way into other restructurings. Because growth cycles are so long, it will be years before it’s clear whether restructuring or additional borrowing will work. The current players will be long gone; the bonds will have changed hands.

Even if macro-linkers are pointless, in the bizarro world of hard currency loans to developing countries, they make perfect sense. They are just the latest chapter in a 50-year saga of Grand Illusions — those obvious fallacies that the characters in this psychodrama refuse to acknowledge.

The original illusion — that enabling developing countries to borrow hard currency under US and UK law would boost development and engender responsible behaviour — has devolved into a pernicious cycle. Third world politicians are, periodically, able to tap international capital markets for unconstrained cash, but when they default, first world investors (the only ones who actually buy the bonds at par) and third world citizens (who rarely benefit much from the money raised anyway) pay the price.

The ‘Grand Illusion’ remains so profitable for so many, that few are willing to recognise that shovelling hard currency at corrupt countries with weak institutions does not render them honest, responsible or richer.

But that doesn’t stop anyone from trying to perpetuate the illusion that lending to developing countries under foreign law is a solid idea by introducing a (sketchy) new feature. As the bond contracts have become functionally unenforceable and the playing field tilted ever more in favour of debtors, creditors struggle to find ways to achieve some leverage and obtain a slightly larger sliver of the pie.

But, really. What’s the point of it all? The cycle never ends. Another tweak, like macro-linkers, may or may not work, but it makes no difference the direction of the sadly predictable play.