Bill Ackman has an enviable record as an investor, but as an equity syndicate banker, he’s learning the ropes the hard way.

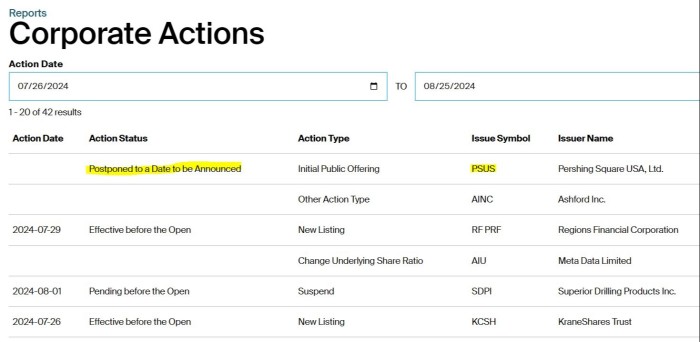

That’s admittedly not his job, but he appears to have assumed that role in marketing the IPO of the Pershing Square USA permanent capital vehicle. And this may explain why the offering was postponed Friday night after downsizing from a record-breaking $25bn to a still-substantial $2.5-$4bn.

And whatever Ackman may say, or his company “clarify”, that’s exactly what has happened.

Normally, the underwriters’ syndicate desks handle all the smooth-talking with prospective investors. They deliver carefully crafted messages that balance marketing finesse and legal restrictions. Navigating what you can and can’t say is a compliance minefield, but for the syndicate managers it’s second nature.

But things can go awry when clients take matters into their own hands.

If an IPO gets a sluggish response, the CEO or controlling shareholder — who is frequently a stupendously wealthy and successful person — might lose patience and take the proverbial bull by the horns. And, in this case, get trampled and gored in the process.

FT Alphaville highlighted last week how Ackman made a major compliance blunder. The latest SEC filing for PSUS reproduces a letter from Ackman to his biggest investors, in which he urges them to put in orders ASAP for the new deal and mentions that Baupost, Putnam, and Teachers Retirement System of Texas have already come into the book.

The letter predicts that robust retail interest would push the share price above its net asset value, unlike most closed-end investment funds (including his own Amsterdam-listed vehicle).

The missive was a rookie error. IPOs have long lead times, and the first commandment at the so-called kick-off meeting is a vow of public silence. For a SEC-registered offering the prospectus has to do all the talking, and any other communications will be deemed a “free-writing prospectus,” potentially exposing issuers to liability and delaying SEC approval.

Ackman’s message might sound harmless to Muggles — why shouldn’t he be able to give his views to his closest professional relationships, who are all very sophisticated parties? — but every capital market wizard knows these are the rules. This is not a regulatory trap for the unwary. That’s why Pershing Square USA had to “disclaim” comments made by its own CEO. Pershing Square will have to let things cool off for a few days or weeks before restarting the deal engines.

So why write it in the first place? Because selling this deal to institutions isn’t easy.

For retail investors, PSUS offers access to Pershing Square’s investment acumen in a way they otherwise don’t have. With more than a million followers on X (formerly Twitter), Ackman can probably garner a large mass of individual investors.

But institutional investors? They are paid to manage money, not paid to pay Bill Ackman to manage money. These vehicles normally trade at a discount to their NAV anyway, and so there’s no reason to buy at IPO, rather than waiting for a discount later on.

PSUS has held over 150 “testing-the-waters” and roadshow meetings, meaning big fund managers were interested in hearing what Ackman had to say. But permanent capital vehicles are very difficult to market to institutional investors on an arm’s-length basis.

The deals usually rely on “friends & family”-type relationships for their institutional demand, such as affiliated entities, personal chums, or money managers who for whatever reason want to curry favour or reciprocate in some way.

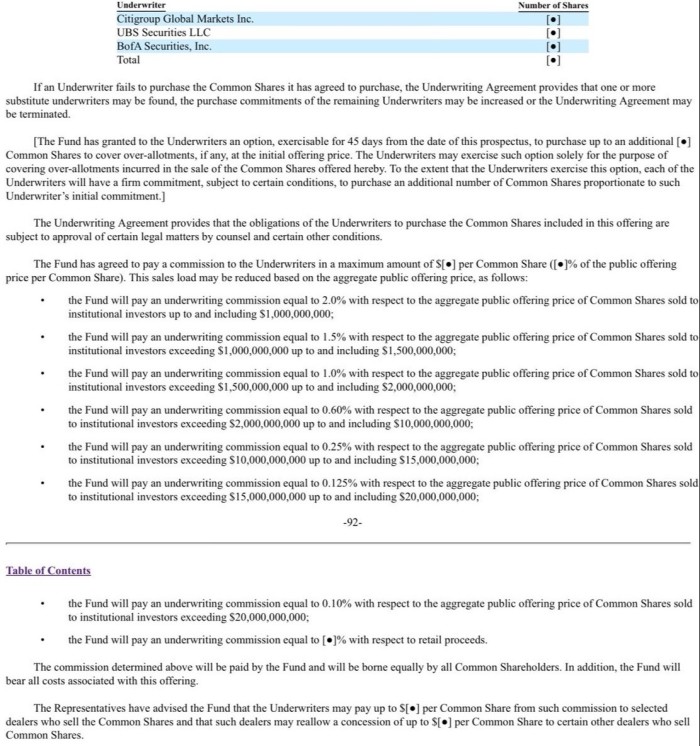

As for the investment banks, they have quite a limited contribution to make, outside of retail distribution. No fund manager cares what lead-left Citi or any of the other underwriters thinks of the vehicle. There’s no equity story, no company projections, no industry outlook to provide. It’s a Pershing Square show, and only its principals can make the case. The banks play mostly a ceremonial-cum-concierge role, taking care of the co-ordination and logistics.

So it was understandable for Ackman to take charge of the actual marketing. But he may have gone too far in supplanting the banks.

The first mistake was to float an overambitious $25bn IPO target. It was never formally announced, but the number was splashed all over the financial media for a reason, and the SEC filings show a sliding scale for underwriter fees even for deal sizes of over $20bn (zoomable version).

In his letter Ackman wrote:

The $25 billion number in the media initially anchored investors in thinking the deal would be too large. Ultimately, I expect this ‘anchoring’ to be helpful to the final outcome.

That’s one way of looking at it. Another way is to say that Pershing Square vastly overestimated investor interest. A strong IPO typically increases in size due to demand; you want to upsize into strength, not downsize by a whopping 90 per cent.

The disclosure of investors was another faux pas. Investor names are kept confidential, unless they are cornerstone investors, who consent to be named in the prospectus and expect to have their orders filled. Cornerstones have become a more common feature on US IPOs in recent years.

The letter mentions a $150mn order from Baupost, $40mn from Putnam and $60mn from Teachers Retirement System of Texas — impressive numbers, but only 10 per cent of the lower end of the downsized size range. It signals that no institution was willing to act as a cornerstone despite extensive pre-marketing.

Then there’s this revealing passage in Ackman’s letter, with FT Alphaville’s emphasis below:

The banks also play a very important role. While they are nominally fiduciaries for us on this deal, ultimately they care more about the regular IPO buyers who buy every deal more than any one issuer. They will always favor Fidelity, Blackrock and others versus us. It is therefore very important that the banks get a sense that a deal’s momentum is building as they convey that feeling of momentum to the capital markets desks of every institutional investor, and the financial advisor community also wants to hear that the institutions are interested and motivated.

One interpretation? The biggest asset managers have not put in significant orders. That’s not something you’d want to advertise if you’re trying to build momentum. You want to entice investors by creating FOMO, not by admitting you need them to pull the deal together.

In short, the offering was oversized, communication norms were flouted, investor names were disclosed in the wrong way, and the letter revealed a lack of institutional buy-in. These mis-steps would earn a failing performance evaluation on any equity syndicate desk — and probably some form of workplace discipline.

When Pershing Square tries again, there’s good reason to believe that they’ll drum up enough demand to go public. Raising even the minimum $2.5bn for a closed-end fund would be a remarkable feat that few other managers could match.

But next time it may be better to leave the syndicate work to the professionals.