Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

South Korea is planning to bring in lower-paid foreign housekeepers to help ease the domestic and childcare workloads of women — and, Seoul hopes, encourage them to have more children.

In the coming weeks, about 100 Filipina workers will arrive in Seoul, where they will receive language and culture training before being assigned work as housekeepers in September. If the pilot project succeeds, a further 1,200 workers could arrive by the middle of next year.

The government’s hope is that more help at home will encourage South Korean women to have children — and raise one of the world’s lowest fertility rates.

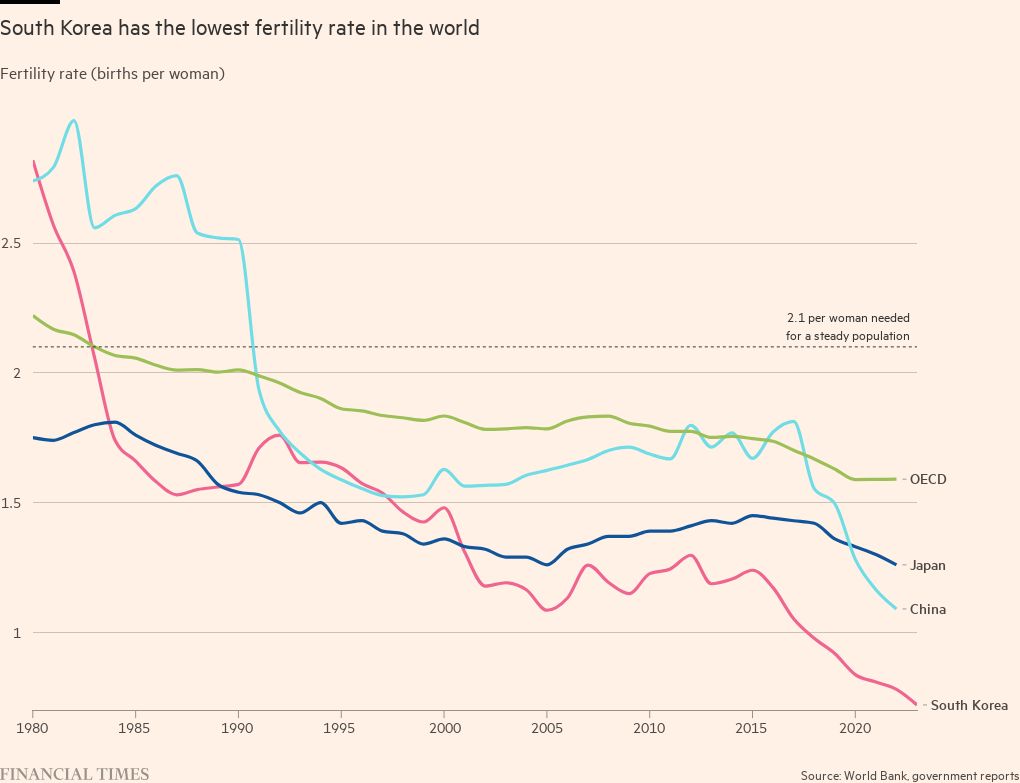

South Korea’s fertility rate is projected to fall to 0.68 this year, far below the 2.1 the OECD says is necessary to ensure a broadly stable population.

“Now, working parents can have one more option to suit their needs, which could help boost birth rates and female economic participation,” said a manager at the labour ministry in charge of the scheme. “If the pilot scheme works well and there is high demand, we can expand it.”

President Yoon Suk Yeol in June declared South Korea’s shrinking population a “national emergency” and the government has this year introduced policies to tackle the demographic crisis. These include expanded financial incentives for would-be parents, raising birth allowances to Won2mn ($1,400), building more houses for young families and increasing financial support for fertility treatment.

It has also promised to expand tax breaks for newly-wed couples, build more nurseries, extend maternity leave to 18 months and make it easier to work flexibly.

Seoul mayor Oh Se-hoon, who has warned of “population extinction”, hopes that the housekeepers scheme could pave the way for looser immigration rules. Immigration is tightly controlled in South Korea, and long-term foreign residents account for just 3.7 per cent of South Korea’s population of 52mn.

“This project is meaningful as a step to cope with low birth rates,” said Oh. “It will also spark more discussions on how to use immigration and foreign workers to take care of the elderly and sick.”

The scheme draws inspiration from Hong Kong and Singapore, which rely heavily on live-in foreign domestic workers largely from the Philippines and Indonesia for domestic labour and childcare.

Seoul said the monthly pay of Won2mn — in line with South Korea’s minimum wage — compared with a market rate of between Won3.5mn and Won4.5mn for live-in South Korean housekeepers. This is substantially more than the roughly $620 minimum wage for live-in foreign workers in Hong Kong, a fact that may work against broader take-up but which Seoul says is necessary to guard against exploitation.

Some working parents in Seoul have argued that Won2mn a month for a housekeeper who works from 9am to 6pm, five days a week, is too much. “If I have to pay Won2mn for the service, I would rather quit my job and do things myself. It is too expensive relative to my income,” said Choi Min-young, a 38-year-old civil servant with three young children.

“Why should I use a foreign nanny when she is not much cheaper, given all the associated problems like cultural differences and language barriers,” said SE Song, a 39-year-old hospital employee. “I don’t think I can enjoy outings, leaving my two-year-old son to a foreign nanny.”

Labour advocates agreed the programme might work best for higher-income families.

“Not many families can afford the programme, given the cost benefits. Outsourcing childcare to cheap foreign labour is not what working parents want while the country’s long working hours are maintained,” said Chang Ha-na, a director at civic group Politicalmamas. “I don’t think the programme can entice women to get married and have children.”

Some also voiced concerns that the foreign helpers could put pressure on wages for South Korean domestic helpers, many of whom are in their 50s and 60s.

Bae Jin-kyung, head of the Korean Women Workers Association, an advocacy group, said reducing working hours would be a more practical solution. South Korea has some of the longest working hours among OECD nations, which deters many women from participating in the workplace. Women’s labour participation is just over 50 per cent, despite the fact many are university-educated.

“The government should focus on reducing working hours so that parents have more time for housework and childcare rather than trying to disrupt the market with cheap foreign labour,” she said.

Since 2006, Seoul has spent about Won380tn on efforts to encourage women to have more children, but given the country’s intense working culture and strict gender norms, it has had limited success.

Some companies have even offered incentives to encourage people to have children. This year, South Korean construction group Booyoung offered workers a $75,000 bonus for each baby, while banks Kookmin and Woori have offered up to five years of parental leave for child care.