Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Rachel Reeves claims she has the worst economic inheritance of any UK chancellor since the second world war. When it comes to the state of the public finances, she has reason to complain, according to economists.

“You have really high taxes, really high debt and yet you have this big need to increase spending,” said Stephen Millard, deputy director at the National Institute of Economic and Social Research. “That is where the government can legitimately claim that they have a particularly bad inheritance.”

What has Labour claimed?

Labour is preparing to unveil on Monday the result of an audit of public spending that is expected to expose an unexpected extra gap between annual expenditures and receipts worth close to £20bn.

The announcement will pave the way for steep tax rises, as the Treasury attempts to bring the share of public debt to GDP on a downward trajectory while still investing to repair public services.

Reeves said in a speech on July 8 that the Treasury probe into spending pressures was needed because Labour had inherited from the Conservatives the “worst set of circumstances since the second world war”.

Conservatives have argued the situation is more benign than the one they inherited in 2010 when David Cameron took over from Gordon Brown as prime minister in the wake of the global financial crisis.

How is the UK economy doing?

On a range of key economic indicators, Reeves’s inheritance looks increasingly positive, according to analysts.

Even after punishing interest-rate increases, unemployment is just 4.4 per cent, about half the rate when the Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition government took office in 2010, and below the rates when Margaret Thatcher won in 1979 and Sir Tony Blair took office in 1997.

Inflation, which peaked at above 11 per cent in 2022, is now on target at 2 per cent, prompting many economists to forecast a cut to Bank of England interest rates as early as next week.

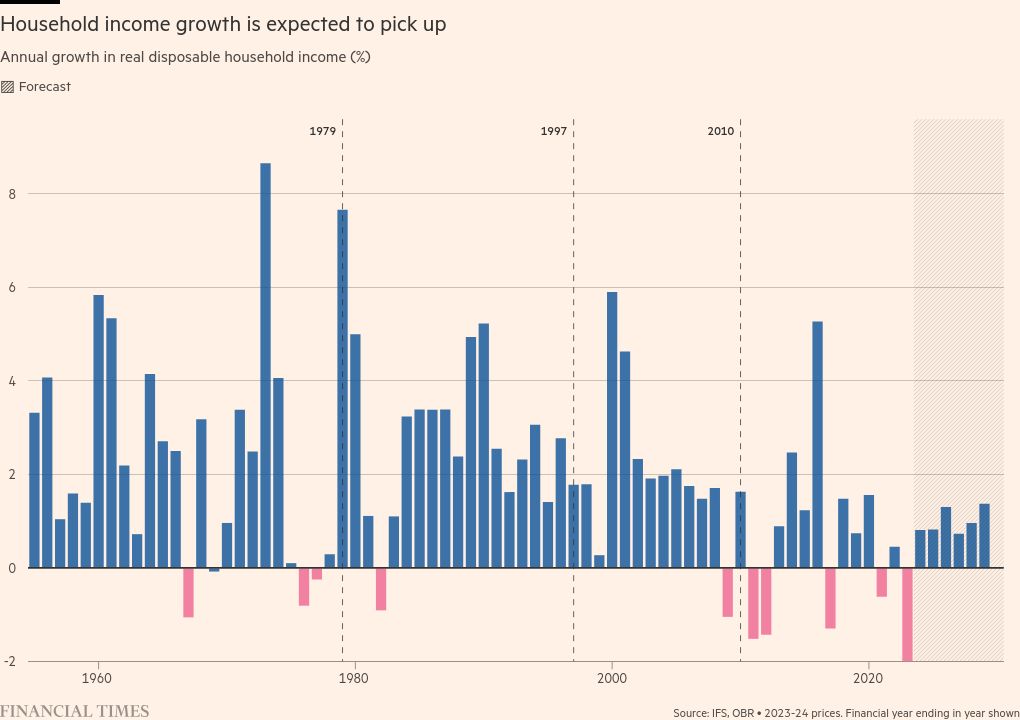

While real disposable incomes were crushed during the inflationary upsurge, they are moving into positive territory and pushing up living standards.

“In terms of some of the standard things people look at — unemployment and inflation — you cannot make the case that the economic inheritance is bad; it is actually very good,” Millard said.

But beneath the surface, some of the underlying drivers of the UK economy are far more troubling. GDP growth has been persistently sluggish, and a far cry from the rapid expansion that helped drive improvements in the public finances under Blair after he took office in 1997.

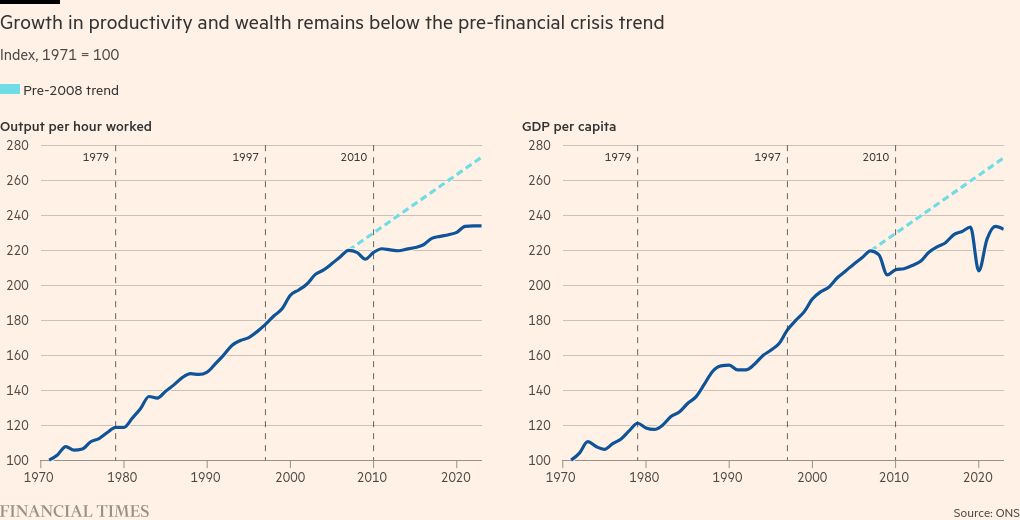

GDP per capita in the first quarter remained below the level it reached on the eve of the pandemic. Indeed, since the financial crisis the country has been trapped in a low-productivity growth spell that is exerting a downward drag on its economic potential.

Why are the public finances particularly weak?

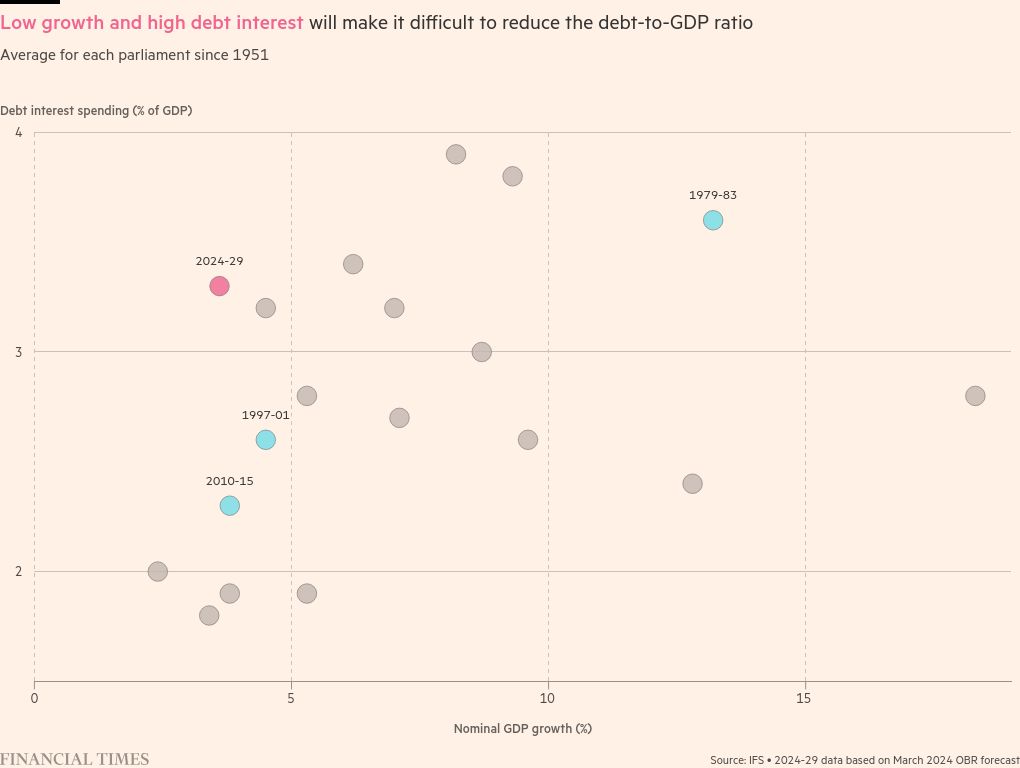

A combination of growth that is well below its pre-financial crisis trend with high borrowing costs and interest payments on the national debt will make it difficult for Reeves to bring government borrowing under control.

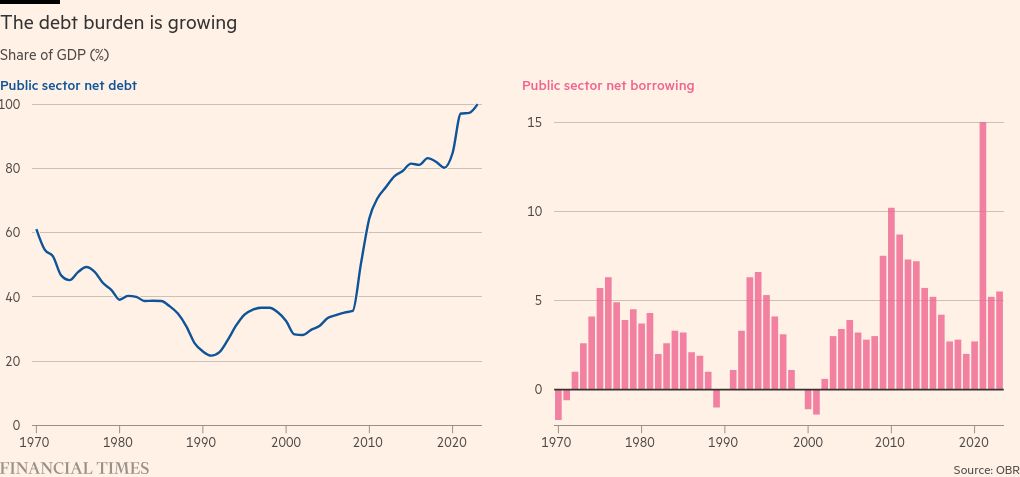

Benjamin Nabarro, UK economist at Citi, argued the “structural position” today is worse than in 2010, even though the headline budget deficit back then was much higher.

The overall debt-to-GDP ratio was lower back then, and funding costs were far lower in 2010, as the BoE slashed rates to near-zero levels and bought up hundreds of billions of pounds worth of government debt.

When Cameron took office, the official interest rate was just 0.5 per cent. It is now 5.25 per cent.

Analysis from the Institute for Fiscal Studies has highlighted the historically unusual challenge of the current combination of low growth and high debt interest levels.

The IMF this month said stabilising the UK’s public debt would require a significant improvement in the difference between government spending and revenue, excluding interest payments.

The gap will need to be 0.8 to 1.4 percentage points of GDP higher per year from 2024-25, according to the IMF, depending on factors including the time horizon envisaged.

The fund estimates real GDP growth would have to sharply accelerate to 2.6 per cent or 2.7 per cent a year from 2024-25 to stabilise the public finances without the need to resort to tough budget measures such as extra tax increases.

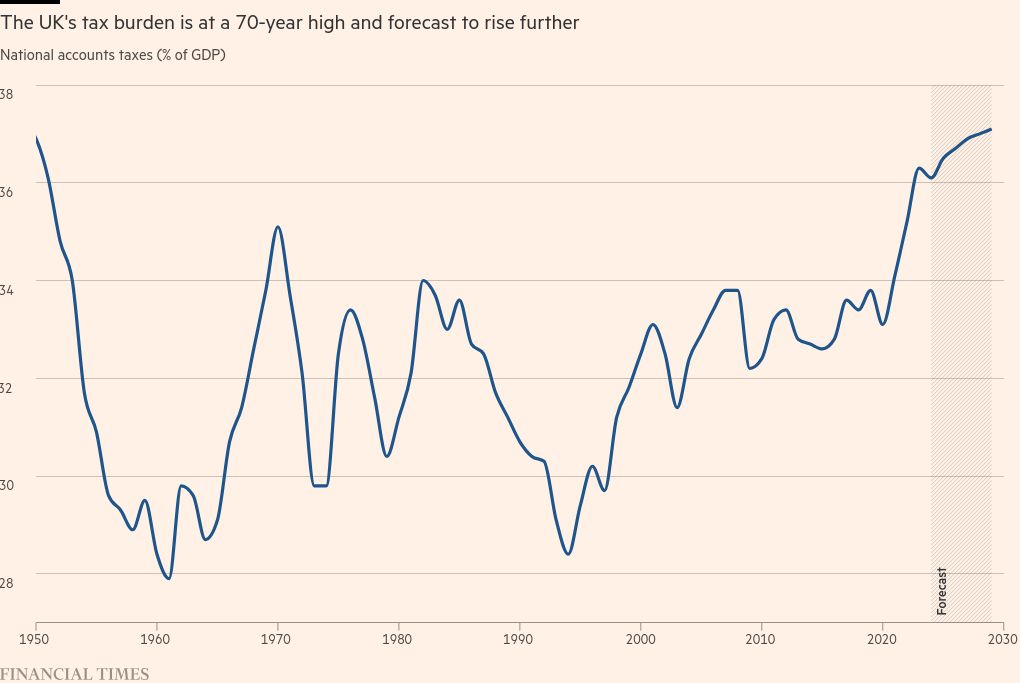

But with the tax burden already nearing a postwar high as a share of GDP, the scope for big increases is more limited than in the past.

Primary surpluses will be necessary to keep debt stable for the first time since the 1990s, according to Nabarro. After a decade of intermittent spending squeezes and low income growth, room for manoeuvre on either tax or spending is “increasingly limited”, he added.

“In 2010 the UK was, fiscally speaking, a sturdy ship in incredibly stormy waters,” he said. “In the period since, the rot has set in.”