Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an onsite version of our Unhedged newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good morning. Ford shares fell 18 per cent yesterday. As our colleagues at Lex point out, the car industry — like Big Spud — is struggling to adjust to the end of the post-pandemic boom. Who’s next to hit the wall? Email us: [email protected] and [email protected]

What is Tesla now?

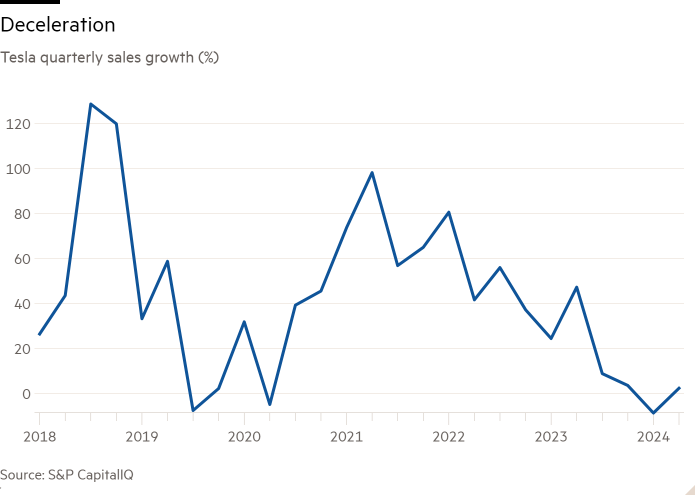

Tesla shares are now 45 per cent below their 2021 peak, and 10 per cent lower than they were at the start of this week. The recent damage was done by Tuesday’s earnings report. Revenues grew just 2 per cent and margins tightened.

The longer-term damage — to the degree that Tesla’s share price can be explained by financial results — probably has something to do with the fact that Tesla’s sales growth has been slowing steadily for three years. It is now downright slow:

On the quarterly earnings call, CEO Elon Musk and his colleagues focused their comments on robots, software and robotaxis — not car sales. The market, despite the downward drift in the share price, appears to buy this pitch. The stock trades at 94 times this year’s expected earnings per share of $2.35. That implies a lot of confidence in Tesla’s ability to build new businesses.

How much confidence? Well, Wall Street analyst consensus is that five years from now, in 2029, Tesla will earn about $9.50 a share. Out-year analyst estimates have to be handled with scepticism, of course. Philippe Houchois, Tesla analyst at Jefferies, argued to us that given the many unknowns, projecting what Tesla will look like in five years’ time is “a fool’s errand”.

Sounds like a job for Unhedged. So here is how, on the back of an envelope, we got to $9.50:

-

We assume that Tesla vehicle revenues reaccelerate, growing at 15 per cent through 2029. This would create a $150bn business, with something like 3 per cent of the global car market, which sounds only moderately crazy.

-

We assume Tesla’s energy infrastructure business continues its strong run, growing to $34bn in revenue by 2029.

-

We are sceptical about Musk’s estimate for the addressable market for humanoid robots (“I think everyone on earth is going to want one. There are 8bn people on earth. So it’s 8bn right there. Then you’ve got all of the industrial uses, which is probably at least as much, if not, way more.”). We assume just $1.6bn in robot revenue by 2029.

-

We assume that self-driving and semi-autonomous cars are a smash hit and that Tesla is the industry leader. We give Tesla’s robotaxi fleet and the autonomous driving software it sells to other car companies a combined $32bn in revenue in 2029.

-

There is probably some other cool stuff that Elon comes up with in the next five years. Let’s say, oh, $12bn dollars worth.

-

We assume that gross margins widen with economies of scale and as software accounts for more of the revenue, but that R&D costs continue to be high.

-

If Musk has a superpower, it is harvesting government subsidies. We therefore assume a 10 per cent net tax rate.

-

In a complete reversal of the historical pattern, we assume the diluted share count is stable.

All that gets us to around $9.50 a share. Readers can take or leave our assumptions as they please. Our point is not that the current valuation is outlandish. Certainly, if you think Tesla is a car company, the share price makes no sense whatsoever, even if you think its car business grows at a super-heroic rate. But, as Houchois proposed to us, you can also see Tesla as a venture capital firm with a great record, which is funded by the cash flows of a pretty good electric car company. How do you value one of those?

(Reiter and Armstrong)

Second-quarter GDP

In the past week, several analytical heavyweights have suggested that the Fed should cut rates next week rather than waiting for September. In an op-ed, former president of the New York Fed Bill Dudley said that rising unemployment, waning household savings and falling inflation justify a July cut. Greg Ip at The Wall Street Journal floated that waiting longer could trigger a recession.

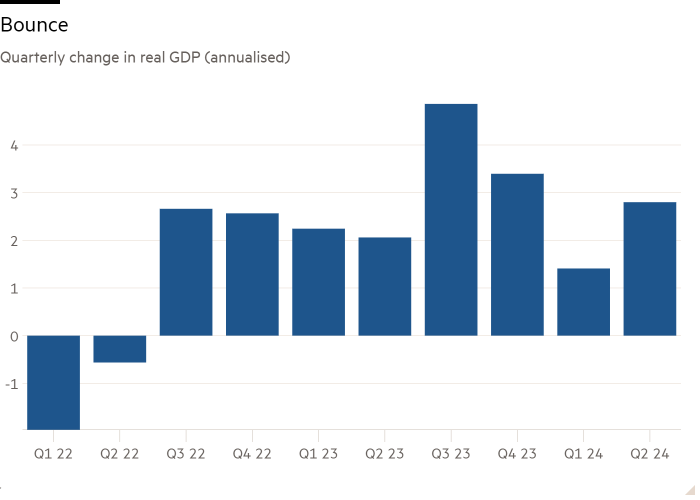

Neither case received much help from yesterday’s second-quarter GDP numbers. Output growth came in hotter than expected at 2.8 per cent annual growth. Final sales to private domestic purchasers — an indicator of consumption closely monitored by the Fed — rose by 2.6 per cent, level with the first quarter. The economy is still chugging along. A July cut, which looked all but impossible, now looks just plain impossible.

That is not to say that interest rates will remain higher for longer than the market currently anticipates, however. A look under the hood shows that this GDP reading was not quite as robust as it may appear.

The Q2 figures were bumped up by a one-off quirk in equipment investment, which lodged an 11.6 per cent period on period growth. According to Stephen Brown from Capital Economics:

Boeing had to delay deliveries because of its [safety] incidents earlier this year . . . Boeing has such a big order book, quarter to quarter its deliveries should be steady. But because they had to do more checks on planes, deliveries were shifted from Q1 to Q2, helping to drive up GDP.

The contribution of overall business equipment investment growth to total GDP growth was around 0.6 points out of the 2.8 annualised.

The other sign that GDP is a shade weaker than it looks is that consumption is outrunning income. Consumption grew at 2.3 per cent, higher than the 1.5 per cent in Q1 and above many economists’ expectations. But given a 1 per cent increase in real disposable personal income, that too should come down soon. People are less likely to spend money they have not earned.

So this jump in GDP still fits a picture of a gently cooling economy, as evidenced by rising unemployment and so-so survey data. Markets continue to price in two to three cuts before the end of the year, starting in September, and that still looks about right to us.

(Reiter)

McDonald’s margins

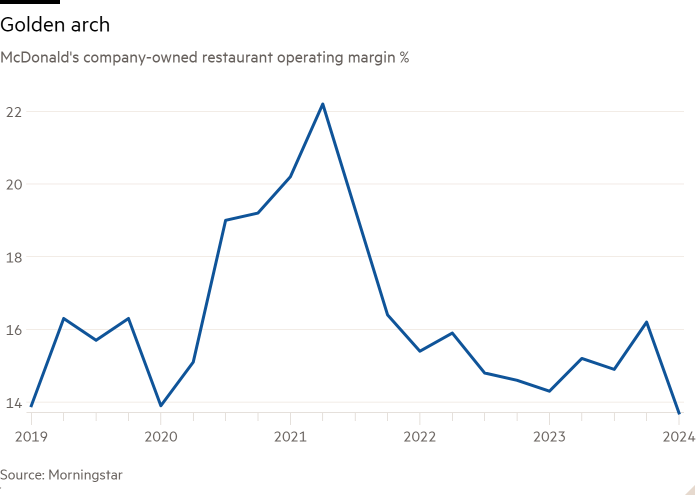

Several readers noted something important about yesterday’s piece on french fries, pricing power and inflation. There, we noted that during the post-pandemic inflationary burst, “restaurants — like many other businesses — increased prices to protect their margins. And more than protect them.” We argued that the era of high margins is now coming to an end, putting a squeeze on suppliers like Lamb Weston.

But the picture is more nuanced than that. McDonald’s has a mostly franchised business model, which makes its operating margin higher and less representative of underlying price dynamics. Sean Dunlop, a restaurant analyst at Morningstar, sent data for McDonald’s-owned restaurant margins — that is, margins excluding fees paid to the company by its franchisees. Restaurant margins look like this:

As you can see, McDonald’s restaurants did see a post-pandemic jump in margins — but it had already subsided two years ago. And that makes things even worse for McDonald’s franchisees (and suppliers). Dunlop writes:

The [pricing] dynamic you allude to is still important, and has created friction between franchisees, who feel pinched, and brand owners, who have done quite well over this [post-pandemic] period. In effect, royalty and rent income [to the brand] increase proportionately to franchise gross sales, so the dependence on price increases to defend margins over the past couple of years has driven substantial margin expansion for brand owners like McDonald’s who bear less of the below the line costs that have inflated so dramatically

With this in mind, it is surprising that the good times at Lamb Weston lasted as long as they did. McDonald’s reports on Monday.

One Good Read

Dead & Co: what does it all mean?

FT Unhedged podcast

Can’t get enough of Unhedged? Listen to our new podcast, for a 15-minute dive into the latest markets news and financial headlines, twice a week. Catch up on past editions of the newsletter here.

Recommended newsletters for you

Swamp Notes — Expert insight on the intersection of money and power in US politics. Sign up here

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Vital news and views on what central banks are thinking, inflation, interest rates and money. Sign up here