The author is former acting governor of the State Bank of Pakistan and an ex-IMF official. Views expressed are his own.

Earlier this month, Pakistan secured a staff-level agreement for a record 24th tryst with the IMF. Conspicuously absent from the accompanying IMF press release was any mention of debt sustainability. This omission is both surprising and disappointing.

Just this May, the IMF came as close to declaring Pakistan’s debt unsustainable as it diplomatically could without triggering a run for the hills by creditors. In its last Staff Report, it warned that Pakistan’s path to debt sustainability was “narrow” amid “acute”, “exceptional” and “uncomfortably high” risks from elevated gross financing needs and scarce external financing:

The end-FY24 debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to decrease markedly, driven by fiscal consolidation and ex-post negative real interest rates. That said, risks to debt sustainability remain acute given very large gross financing needs and the persistent challenges in obtaining external financing, and that real interest rates are projected to become an adverse driver of debt dynamics in the coming years.

In Fundspeak, this was an SOS call. Yet barely a month and a half later, the Fund and the Pakistani government seem intent on walking back this candour and kicking the can down the road. The consequences of this “extend and pretend” gamble will probably be tragic.

It will impose unbearable austerity on a population already laid low by stagnant per capita income over the past decade, a historic cost of living crisis and endemic political dysfunction. As witnessed in Kenya last month, it could spark a major social rebellion in the world’s fifth-largest country. Moreover, it will lead to deeper losses for creditors when the inevitable reckoning comes. When the dust settles, the already sullied image of the IMF in Pakistan could be in tatters.

Some will object to this bleak prognosis. After all, debt sustainability is usually a judgment call that lies in the eye of the beholder. However, some facts are incontrovertible.

According to the IMF, for each of the next five years, Pakistan owes the world an average of $19bn in principal repayments, or more than half of its export revenues. It will also need a minimum of $6bn every year to finance even threadbare current account deficits forecasts, bringing total external financing needs to at least $25bn a year between now and 2029. Pakistan has foreign exchange reserves of less than $9.5bn.

That’s not all. For each of the next five years, the government will need to pay an average of 6.5 per cent of GDP in interest on the debt it already owes to residents and foreigners. Pakistan’s total tax take is barely 10 per cent of GDP.

Let those facts sink in. Unchecked, things will fall apart. And it’s hard to see how Pakistan can extricate itself from this predicament without debt relief.

For starters, Pakistan cannot meet its external financing needs without incurring more government debt. This is because it doesn’t really attract any meaningful FDI (less than $2bn every year) and its private sector is incapable of generating capital inflows from abroad.

Just take the latest IMF loan for example. The $7bn that the IMF will lend is less than the amount that Pakistan needs to repay the Fund over the next four years — a classic case of ever-greening and a worrying sign of a brewing Ponzi scheme.

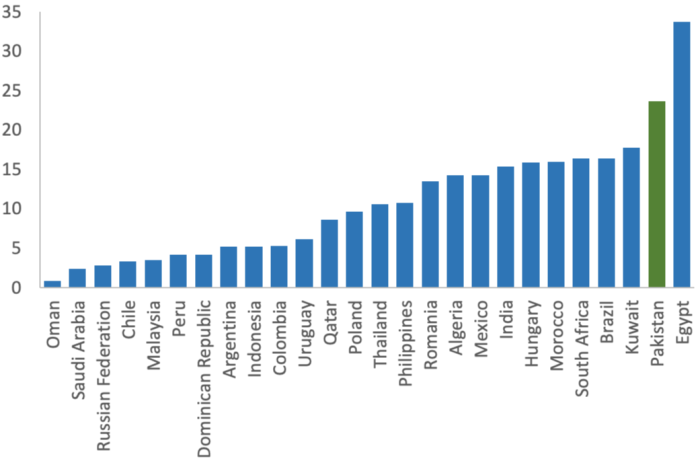

At 77 per cent of GDP, Pakistan’s public debt is already above levels considered excessive for an emerging market. Further debt accumulation will be dangerous. And at 24 per cent of GDP, its gross financing needs (the sum of the budget deficit and debt coming due over the next year) are second only to Egypt in the emerging world.

As a result, borrowing abroad at a reasonable cost will be very difficult, and the debt overhang will continue to weigh on domestic investment and economic growth.

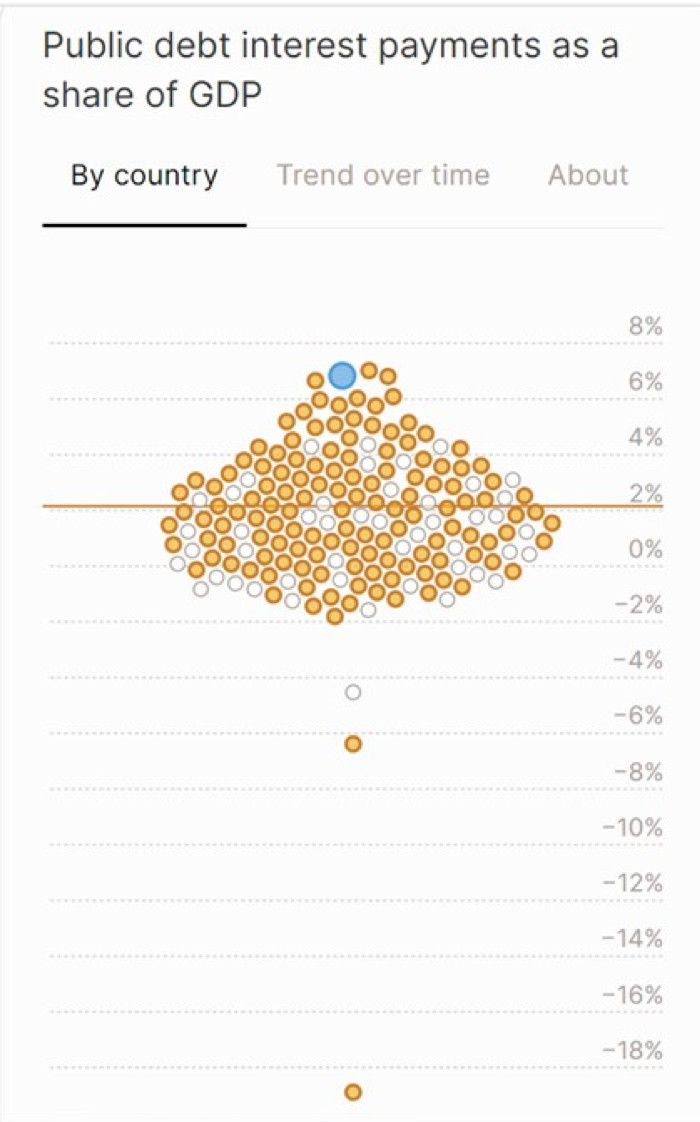

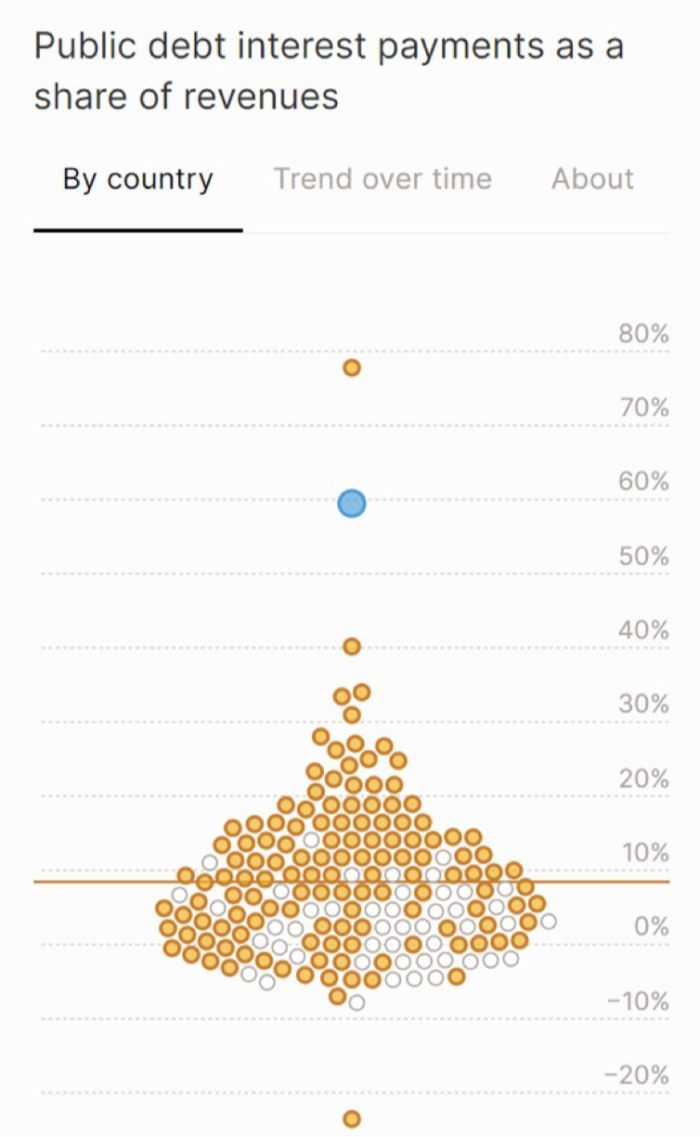

Indeed, things have already come to a head. Consider the following troubling exhibits — courtesy of UNCTAD’s World of Debt Dashboard — with Pakistan shown as the blue dot and other developing countries in orange.

At 6 per cent, Pakistan’s government pays more on interest as a share of the economy than any other country in the developing world.

And at 65 per cent, it has the second highest interest payments to government revenue ratio in the world, after Sri Lanka.

As a result of this heavy interest burden, the government has no resources left for social spending, which languishes among the bottom in the world.

This is terrible as social spending is critical for upgrading the skills of the population and boosting the quality of jobs, exports and foreign investment in the economy.

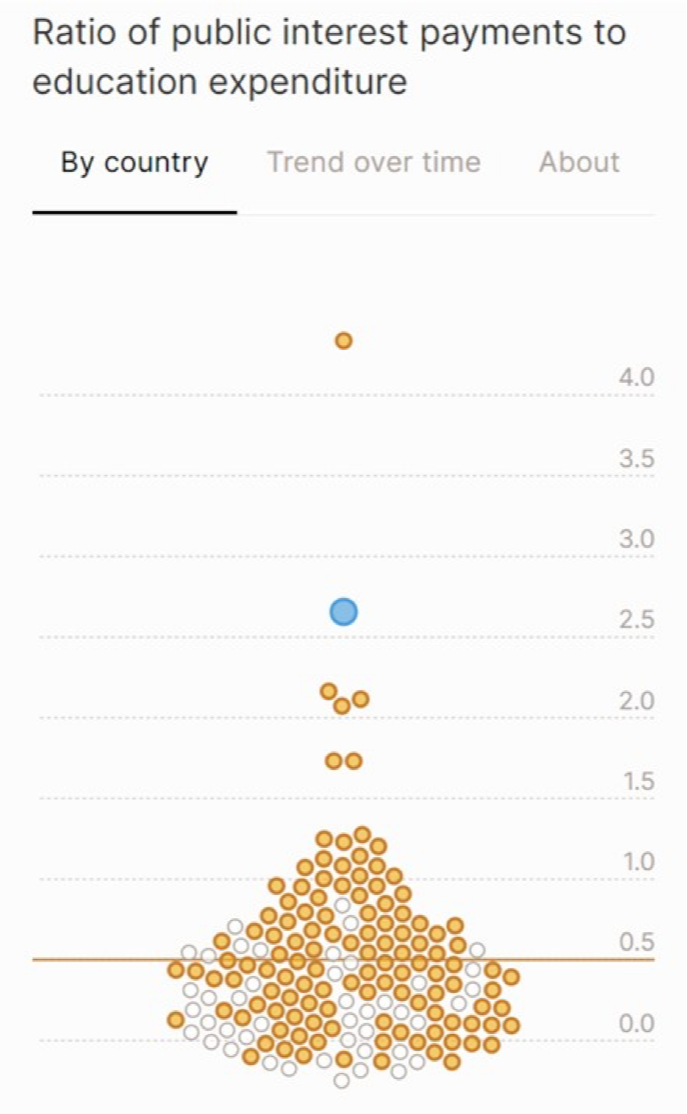

In fact, Pakistan’s government spends almost three times more on interest than on education, again the second worst ratio in the developing world after Sri Lanka.

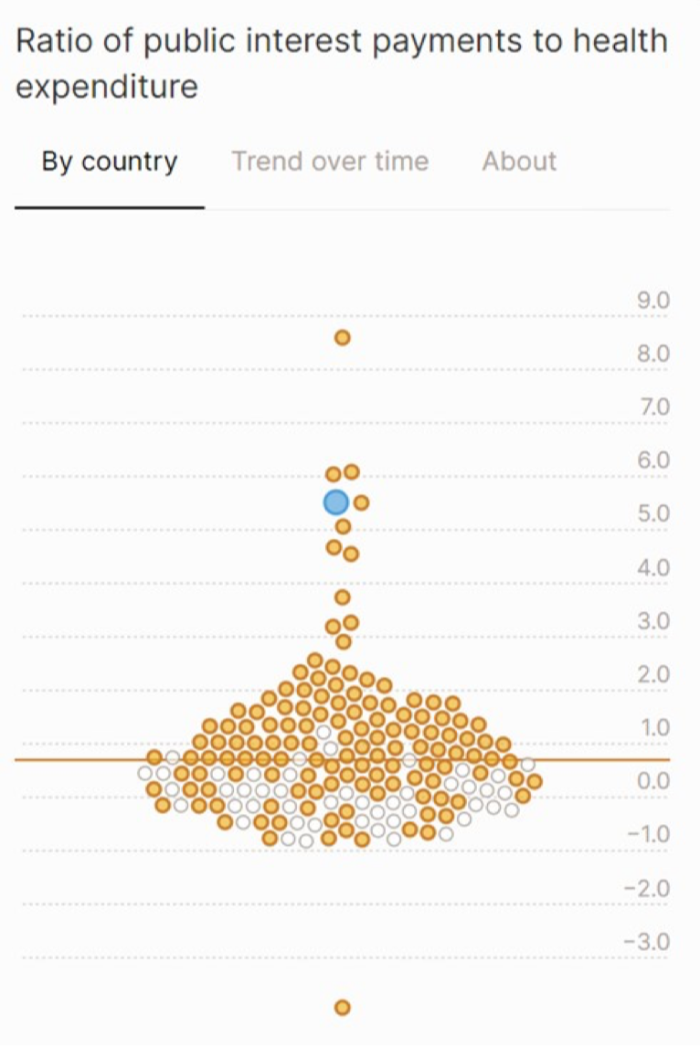

Similarly, it spends almost six times more on interest than it does on health, behind only Yemen, Angola and Egypt. Is it any wonder then that 40 per cent of children under the age of five are stunted and 26 million are out of school?

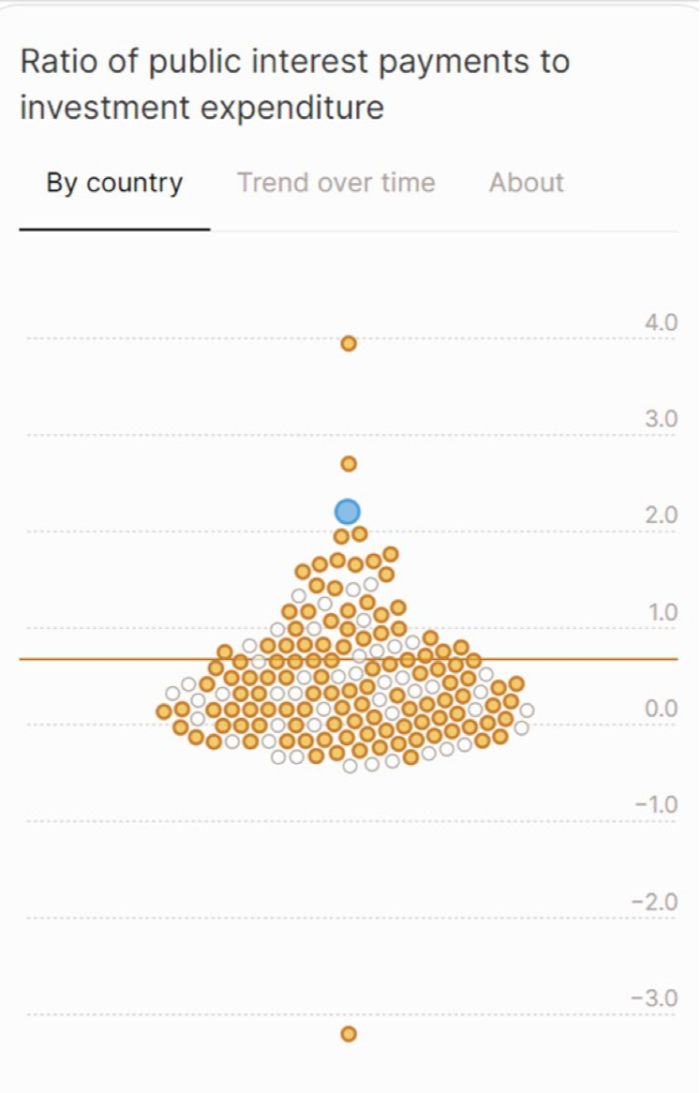

Large debt repayment obligations are also crowding out other spending vital for the country’s future. The government spends twice as much on interest as on investment, behind only Angola and Lebanon.

Partly as a result, Pakistan invests just 12 per cent of GDP, two and a half times less than what is generally considered as necessary for sustained growth.

Worryingly, these problems are here to stay. Even if Pakistan’s revenues were to miraculously increase by 3 per cent of GDP over the next three years — as assumed in the forthcoming Fund program — interest would still consume around half of government revenue. All of this demonstrates how Pakistan’s debts are unsustainable.

Another way to get at this is to peruse the IMF’s own debt sustainability analysis (DSA). Unfortunately, the same conclusion emerges.

According to the latest IMF DSA conducted in January, the government will need to start running a primary surplus this year and maintain it for years to come for Pakistan’s debt to be sustainable. The last time Pakistan ran a surplus was 20 years ago during the war on terror, when foreign grants were pouring in.

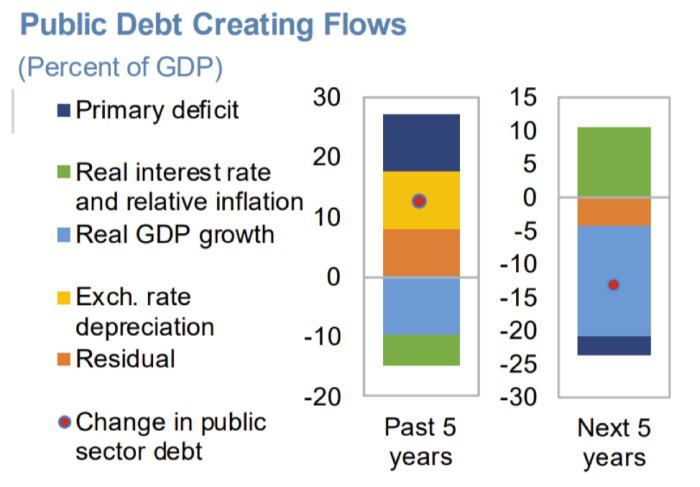

Basically, the IMF says that all major macroeconomic trends of the past will somehow need to be dramatically reversed for Pakistan’s debt to be sustainable: budgets will need to be much tighter (dark blue bar); the currency will need to be stable (yellow bar); and growth a lot higher (light blue bar); despite much tighter fiscal and monetary policy (green bar).

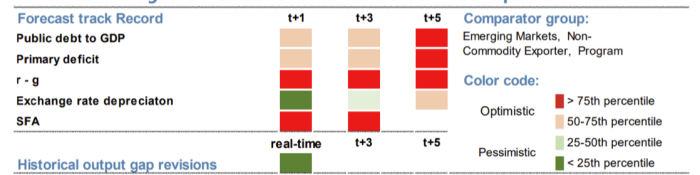

Another warning sign is that the IMF’s forecasts of Pakistan’s public debt and key variables that affect it — the primary deficit, real interest rates (r), growth (g) and the exchange rate — have historically all been wildly over-optimistic, as denoted by the flashing red lights on its realism score board. Why should this time be any different.

So make up your own mind about where this leaves debt sustainability.

Unfortunately, as seen in so many cases across the world, the consequences of not calling it like it is will be an unrealistic painful amount of fiscal consolidation – previewed by a much-criticised budget recently passed by the government – no real space to protect the vulnerable and a bigger eventual reckoning.

It’s especially disappointing that the IMF has ignored its own latest cross-country research, which shows that fiscal consolidations fail to make debt more sustainable by undermining growth, particularly when the global environment is weak and uncertain.

Instead, in cases of dire distress like Pakistan, the pace of fiscal consolidation must be moderated by combining it with debt restructuring. A far more prudent route than the austerity about to be unleashed on Pakistan would be to reprofile its public debt so that resources can be freed up for critically-needed spending on development and the climate.

Pakistan is a canary in the coal-mine in a world where almost 60 countries are drowning in debt while facing significant development spending needs and monumental risks from climate change. It is precisely in cases like this that debt relief—and truth-telling—are most needed.