India’s Narendra Modi faces an early test to his third term in office as the prime minister prepares to unveil a budget that must balance the demands of new coalition partners while putting forward an economic vision that reinforces confidence after an unexpected election disappointment.

Modi’s Bharatiya Janata party was re-elected to a historic third term in June but unexpectedly lost its parliamentary majority, forcing the prime minister to depend on two regional “kingmakers” to see off a resurgent opposition.

Those allies, the Telugu Desam party from southern Andhra Pradesh and Janata Dal (United) in northern Bihar, are demanding billions of dollars in financing for their states ahead of the government’s first budget, which will be delivered on Tuesday for the financial year ending March 2025.

Neelayapalem Vijay Kumar, a spokesperson for the TDP, said the party wanted to “utilise the clout” it has as a coalition partner to secure funding for roads, an oil refinery and Amaravati, a new “high-tech” state capital.

The JDU, meanwhile, has requested airports, medical colleges and infrastructure projects including power plants and new roads. “A new government has been formed and our party, the JDU, is part of that,” said spokesperson Kishan Chand Tyagi. “The expectations of the people of Bihar have risen.”

Nomura estimates that requests from coalition partners could cost about 0.2 per cent of India’s GDP this year.

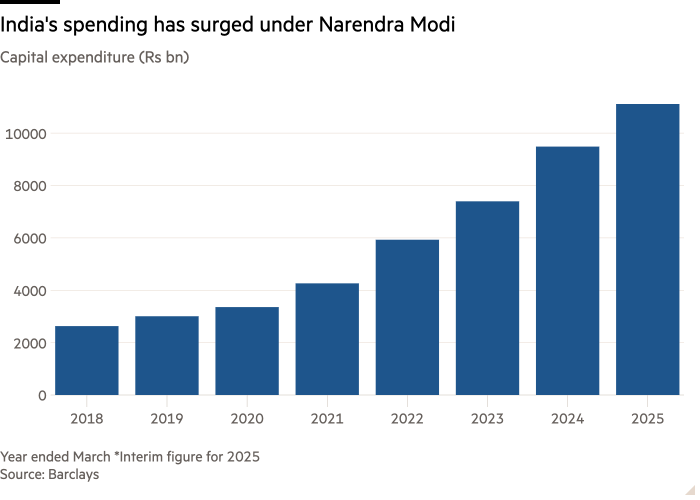

Modi, a domineering leader known for bold, surprise announcements, has never ruled in a minority government. Investors are watching closely for an early indication of whether he can adapt to the compromises required of coalition politics, while continuing the fiscal consolidation and business-friendly reforms that he hopes will make India a global manufacturing and tech hub to rival China.

“Economic transformation wouldn’t have happened if Modi hadn’t forced it,” said one person close to the party. But they added that the BJP would have to “change their style of working, be a little more accommodative and make some allies along the way — whether that will be adequate, I don’t know”.

The prime minister also faces popular anger over chronic hardship in rural areas and widespread joblessness in the country of 1.4bn, despite economic growth of more than 6 per cent a year. Finding solutions for these problems, which many analysts blame for the BJP’s disappointing election performance, will be essential to securing his domestic position and quelling questions about how many more years he should remain in charge.

Shumita Deveshwar, senior director of India research at GlobalData TS Lombard, said one of the government’s strengths was its ability to “portray itself to investors well”.

“But, on the other side, we’ve seen with the election results that people are getting impatient, and voters are looking to see what the government will do next,” she said. “There’s no quick fix.”

The BJP, which has in recent years increased spending on infrastructure, welfare and subsidy schemes to attract foreign manufacturers, has dismissed concerns about its record and appointed a largely unchanged cabinet last month.

The new budget will be buoyed by a record Rs2.1tn ($25bn) transfer from the Reserve Bank of India this year, part of an annual payout from the bank’s surplus funds.

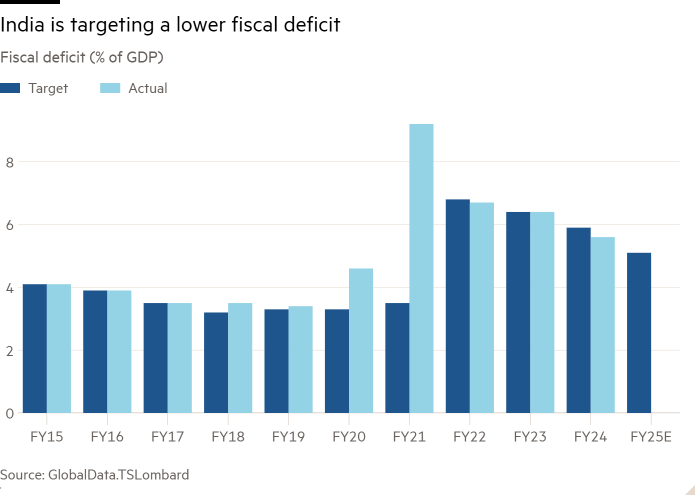

Analysts expect this extra cash should help Modi’s government maintain or even lower the fiscal deficit from its current target of 5.1 per cent, compared with 5.8 per cent the previous fiscal year, even if it increases spending on infrastructure or for coalition states.

The coalition partners “are fully aligned” with the BJP’s economic vision, said Narendra Taneja, a former spokesperson for the ruling party. “There will always be people who will be submitting a wish list . . . but are there any serious differences? No. Is there any bad blood? No.”

Modi’s return has been welcomed by big businesses that have thrived on BJP policies such as corporate tax cuts. “They will not fix what is not broken,” said R Shankar Raman, chief financial officer of Larsen & Toubro, India’s largest engineering and construction company, which has been in talks to restart development of the city of Amaravati. “There is merit in continuity.”

But the BJP also enters its third term saddled with daunting economic challenges. Private investment has not picked up and inequality has risen to a historic level under Modi, with the richest 1 per cent of Indians holding 40 per cent of the nation’s wealth, according to a paper this year from the World Inequality Lab. The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy put youth unemployment at 45 per cent last year.

Modi may have limited time to show results. Two BJP-controlled and allied states, the business hubs of Maharashtra and Haryana, will hold elections this year, and analysts expect a tough fight after the opposition made strong gains during the parliamentary polls.

Pronab Sen, India’s former chief statistician, warned that perceptions of favouritism to Andhra Pradesh and Bihar in the budget would “open a can of worms” and inflame tensions with other states.

But he suggested that India’s new political landscape could prove an economic boon if the BJP becomes adept at consensus-building, which could help it push through more economic reforms.

“What was happening at least over the last six, seven years was that most decision-making was completely unilateral,” he said. Now, “they’re going to have to convince their partners, [and] if they’re sensible they’ll open it up further to all states”.