A former Moncton hospital nurse who was brutally assaulted on the job five years ago has written a book about her road to recovery and her search for social justice, in the hopes it will help other victims of workplace violence.

Natasha Poirier, a nurse manager at the Dr. Georges-L.-Dumont University Hospital Centre, was cornered in her office on March 11, 2019, and attacked by the husband of a patient who wanted his wife moved to a quieter room.

Bruce (Randy) Van Horlick pulled Poirier from her chair by her hair, punched her on the temple, threw her against a wall, twisted her arm and several fingers backward, and assaulted another nurse, Teresa Thibeault, who tried to intervene.

The attack lasted 11 minutes. Poirier says her life was “forever changed.”

She sustained a brain injury, suffers from daily chronic pain, post-traumatic stress disorder and major depressive disorder.

“I have 24 symptoms that I have to contend with every single day,” she said — conditions so debilitating that WorkSafeNB, Health Canada, Blue Cross and the Canada Pension Plan all concluded she could not return to her job with Vitalité Health Network.

Natasha Poirier was viciously attacked while on shift at a Moncton hospital five years ago. She’s been sharing her experience in the hopes of helping other victims of workplace violence.

Van Horlick, 74, was found guilty in 2020 of two criminal charges of assault and sentenced to six months in jail.

Poirier also sued Van Horlick, and in 2022 he was ordered to pay her $1.3 million, although she has not yet received any money, she said.

‘Code of silence’

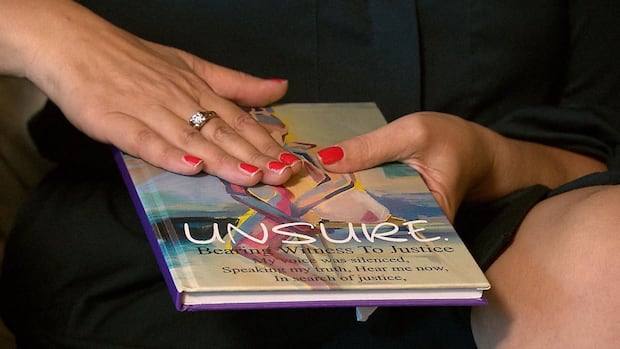

According to Poirier’s book, Unsure: Bearing Witness to Justice, written with the help of a ghostwriting company, workplace violence against nurses and other health-care workers is a “global epidemic” that “demands attention.”

“We must collectively declare that it is an occupational hazard,” she wrote. “The time to say ‘Enough is Enough!!!’ has arrived.”

Poirier suffered two previous workplace assaults during her 25-year career, including getting kicked in the stomach by a patient when she was eight months pregnant, she said.

She has also witnessed colleagues being pushed, spat upon, threatened, and having urine and feces thrown at them.

But few speak out, Poirier said.

“There’s an unspoken rule, the ‘code of silence,’ I would call it, and the fear of retaliation, or the fear of losing their jobs, the fear of being blamed, judged, the fear of being seen as weak, and the guilt and shame — kind of all those factors silence the health-care workers, I believe.

“This has been a culture that’s been around for years and years. But hopefully with the new generation that’s coming in, they’re going to be more apt to use their voices and express their discontentment and not accept the status quo.”

If my voice can help, or can shed light on the silence surrounding violence, then perhaps this might be my future … contribution.– Natasha Poirier, nurse, victim of assault and author

Poirier hopes sharing her experience and how she “weathered through the storm of trauma” will help raise awareness about the situation and the need for “more robust security, especially in hospital settings.”

She also hopes it will help “victims” on their journey to being “survivors” realize that “it is possible to obtain a better quality of life, with time.”

“If my voice can help, or can shed light on the silence surrounding violence, then perhaps this might be my future … contribution.”

National union praises book

Linda Silas, president of the Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions, said the book — which was released in early May, during national nursing week — is already making a difference, and she plans to promote it.

“It’s a personal story that I’m sure was very hard to write, but it sends a message to all of us, including unions, governments, employers, that we need to do better in protecting nurses and health-care workers.”

Workplace violence in the industry is “way too common,” said Silas.

A survey in January of more than 5,000 nurses across the country found nine in 10 had experienced some form of violence in the previous year, including physical attacks, emotional abuse and harassment, she said.

The number rises every year, said Silas, partly because patients and their families are increasingly frustrated.

“They’re in hallways. They wait too long in the ER, they wait too long for their treatment They ring that bell, nobody comes. There’s not enough nurses, not enough health-care workers to answer the needs.

“So there’s a frustration level for sure, but it’s not an excuse to physically or verbally abuse your staff.”

Silas also said she believes nurses are starting to feel more comfortable reporting incidents.

‘When I was practising as a nurse, you’d feel like you were ashamed if you reported it. You know, ‘What did you do wrong?’

“And now we’re trying gradually to change the culture with nurses and health-care workers, that you deserve a safe working environment and you need to speak up. And that’s what Natasha Poirier and her colleague did, is speak up.”

Navigating ‘the aftermath’

It wasn’t easy, said Poirier. She felt abandoned by her employer following Van Horlick’s attack.

“When I decided to have the RCMP called because of the assault, I wasn’t patted on the back for requesting that call, or I wasn’t encouraged to continue my journey in obtaining justice for myself.”

And while she had the support of family, colleagues and the community, Poirier says she still felt alone.

“I really think that workplace assaults are not understood … because not a lot of people talk about the aftermath” — not only on the victims, but on those around them, said Poirier.

The attack had a significant impact on her family, she said, referring to the pain of having to accept their loved one will never be the same, as well as on her co-workers, who suffered “vicarious trauma.”

The criminal trial, which lasted a year and a half, made her feel like she “was being chewed up and spit out alive,” she said.

Then there was the civil trial, which was also draining.

Poirier said she tried to continue her part-time nursing work with Veterans Affairs, but even reduced hours proved too much and she had to stop in November 2022.

“As the day progresses and my brain gets more tired, I’ll get more emotional, my brain will slow down, I’ll start word-searching, I’ll be more forgetful, and all the symptoms … reappear,” she said.

“But I do have good days, and those days I cherish and I try to be as productive as I can.”

Part of her healing and reclaiming her “sense of wholeness,” she said, has been telling her story on her own terms and hearing from other survivors, including women in violent relationships.

“This book is a message of hope — a testament to the strength within each of us to overcome adversity,” she wrote.

“I hope to provide solace, inspiration, and a call to action for change.”