June is National Indigenous History Month. To celebrate our accomplishments, CBC Indigenous is highlighting First Nations, Inuit and Métis trailblazers in law, medicine, science, sports — and beyond.

Over a century since the first Native American man stepped up to home plate in Major League Baseball, Indigenous players say there’s lots of talented youth who want a shot at chasing major league dreams.

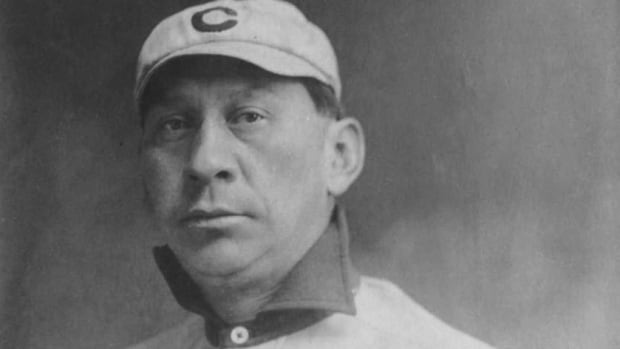

Louis Sockalexis, a member of the Penobscot Indian Tribe in Maine, is believed to be the first Native American to play professionally — and he did so nearly 50 years before Jackie Robinson debuted for the Brooklyn Dodgers, breaking Major League Baseball’s colour barrier.

Sockalexis signed a contract with the Cleveland Spiders in 1897 after playing college baseball for two different teams.

As a 25-year-old, Sockalexis hit .388 over 336 at bats in his rookie season and he struck out just over 10 per cent of the time he appeared at the plate — clearly a man with an eye for the strike zone.

Sockalexis’s play on the diamond captured fans’ imaginations and garnered media attention in many cities he visited.

Newspaper stories from the late 1800s — often loaded with trope-filled descriptions of the man — also detailed his feats on the field, from near-impossible catches to long throws preventing runs, to driving in game-winning runs.

Those papers also detail Sockalexis’s decline. Some cite injuries he incurred on the field; others recount the man’s alcohol abuse.

Sockalexis would phase out of Major League Baseball after the 1899 season. After Sockalexis’s major league career was over newspapers took to describing numerous arrests.

His story was retold at various points in the last 20 years. CBC Indigenous spoke with a descendant when Cleveland ditched the use of a racist mascot. ESPN released a short documentary about him, and his story was shared by media when the Cleveland team changed its name ahead of the 2022 season.

But while his accomplishments are remembered by some, not everyone today is aware of Sockalexis’s story.

Kaleb Thomas, a Mohawk pitcher from Six Nations of the Grand River currently playing NCAA Division I level baseball with Missouri State University said he hadn’t heard Sockalexis’s story.

Thomas himself was the first Indigenous player on Canada’s Junior National team.

“I thought it was really cool to see that, even back then, there’s Indigenous people playing baseball,” Thomas told CBC Indigenous.

“There’s always been someone [Indigenous] playing baseball for as long as it was around.”

‘I think baseball is growing’

Thomas, who dreams of becoming a Major League Baseball pitcher, said he tries to motivate any kid to play sports.

“I use my platform to promote healthy being, and being active and following dreams,” Thomas said.

The sport, he said, has helped him grow and “come out of his shell.” Three years ago he said he travelled for baseball, by air, alone, for the first time.

Thomas participated in the 2023 North American Indigenous Games (NAIG) in Halifax and he said he realized there just how many talented Indigenous baseball players there are today.

“I think baseball is growing more and more each year in the Indigenous communities, and it’s wonderful to see that,” Thomas said.

WATCH | Indigenous baseball players still breaking barriers:

“I know that hockey and lacrosse are the biggest sports, but I think it’s just great to see people expanding their horizons and trying other sports and hopefully making a name for themselves one day.”

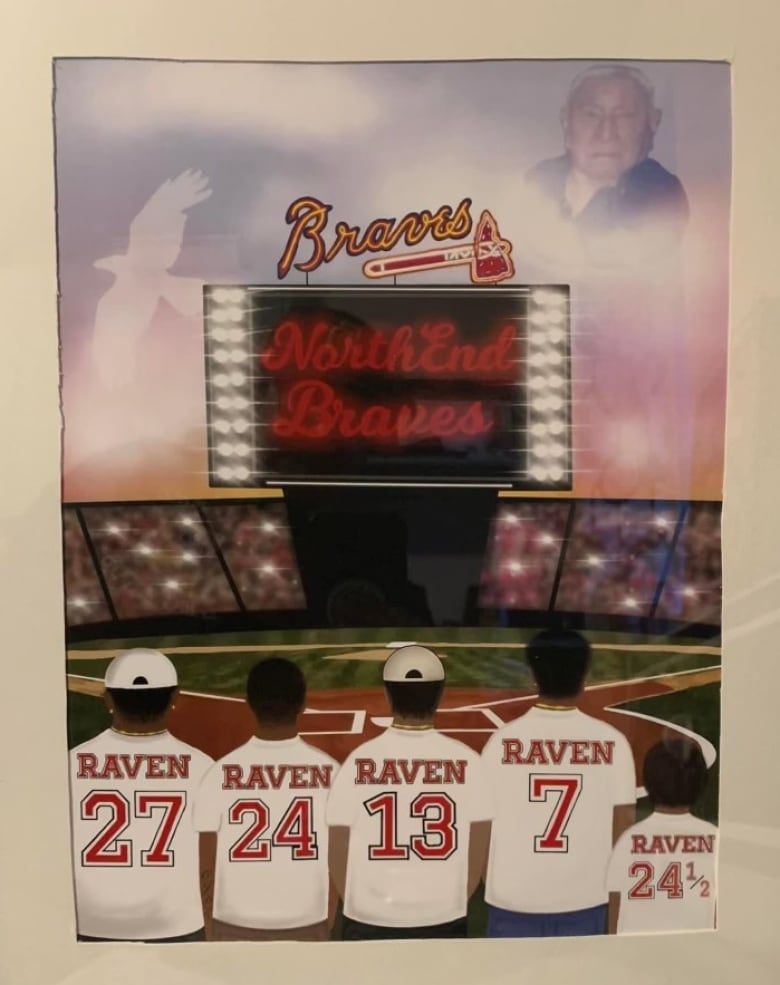

One of those players trying to make a name for themselves in baseball is Bryce Raven from Brokenhead Ojibway Nation, who lives in Winnipeg. The 19-year-old plays softball, slo-pitch and is part of a junior-level travel baseball team in Manitoba.

Like Thomas, Bryce was at the NAIG in Halifax, pitching for Team Manitoba and earning a gold medal.

His great-grandfather, his grandmother, his dad and older brothers also play and he said he was swinging a bat before he could join a team officially for T-ball.

Outreach needed, says player

He plays for the North End Legends, a team his great-grandfather founded decades ago and managed by his dad, Cory Raven.

“It makes me proud, just knowing my grandfather is watching us play ball,” Cory said.

“I’m a little older now these days, but I still try and play. I actually get to enjoy my kids playing ball, seeing my team play ball every time we hit the field, it’s just a great, great feeling.”

Bryce wasn’t aware of Louis Sockalexis’s story, but was able to name a retired Native American Major Leaguer in Jacoby Ellsbury, who played for the Boston Red Sox and the New York Yankees as an outfielder from 2007 to 2017.

Like Ellsbury, he is a natural left-hander (a player who throws and hits lefty) and spends some time in the outfield, like the former pro.

In order to grow the game so more Indigenous players can chase major league dreams, Bryce said teams and organizations should be in their communities, or reaching out to them.

“There’s always kids out there. They don’t really get a chance to play or anything like that,” he said.

“Seeing if they want to join, and starting up camps and things like that, would be a good thing. [You could] see where it takes off.”

Bryce said he’s looking at colleges in the United States where he can play baseball and it leaves his dad Cory with mixed emotions.

“It’s something he needs to do,” Cory said.

“It’s kind of a good feeling, but it’s kind of sad because he’s got to go away.”