Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Sovereign bonds myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Elias Ferrer is director of Orinoco Research.

Many people think Venezuelan debt is a lost cause, a game only to be played by rinky-dink hedge funds. After all, the bonds have been in default since 2017 — a longer period in limbo than even Argentina suffered after its 2001 default.

The bonds were issued by the Venezuela government and two state-owned companies, national oil champion PDVSA and the utility Elecar. With accrued interest, we’re looking at $92bn. A few more years of past-due interest heaping up and Venezuela’s debt restructuring might even supplant Argentina’s in size as well as lengthiness.

Is a resolution possible? Yes, because either the US and Venezuela will eventually come to a tacit understanding or there will be a change of government in Caracas. But it will probably be messy and take time.

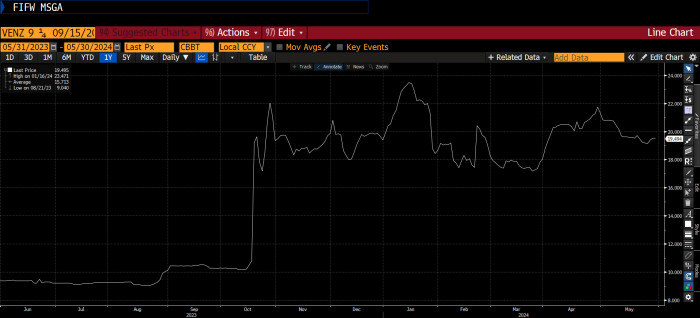

Markets certainly seem sceptical. Even the US lifting a ban on even trading Venezuelan bonds last year, and JPMorgan subsequently announcing that they will make a comeback in its emerging market bond indices only caused a modest rally. Prices went from 5-10 cents on the dollar to 11-20, depending on the specific bond. Those prices reflect that even though hopes have increased this year, not many investors see a restructuring on the horizon.

The biggest obstacle is Washington, not Caracas. The US doesn’t recognise Nicolás Maduro as Venezuela’s president, and has told creditors to only speak to an alternative government in exile. There’s also an Ofac measure against Venezuela issuing new debt — which is necessary to restructure its bonds (workouts are structured as the exchange of old defaulted bonds with new but less valuable ones).

And while the US might have lifted its prohibition on secondary market trading of Venezuelan bonds, it reimposed tough sanctions on its oil industry last month, after Maduro backtracked on a promise to allow free and fair elections.

The scale of the debt problem is also obviously huge. In addition to the bonds and the mounting heap of missed interest payments there’s another $57.2bn of other external debt, including $23.1bn in various arbitration awards, and $13bn in bilateral debt owed to China. Restructuring all this will require a Herculean effort, as Venezuela’s economy has shrivelled to just $100bn this year.

However, the Venezuelan government recently seems to be interested in tackling the festering default, hoping that resolving it could hold the key to the country’s reintegration with global financial markets and Venezuela’s recovery.

The Ministry of Economy and Finance has actually already been discreetly engaging with creditors for years. It hired the law firm Dentons for advice and defence of its overseas assets back in 2017, but two years ago it also brought in Rothschild to help map out its tangled liabilities — although this only hit the news this April.

The finance ministry has also tapped up two foreigners to advise them on policy and on the eventual restructuring: Patricio Rivera and Fausto Herrera, both former Ecuadorean finance ministers that were involved in Ecuador’s own debt restructuring a decade ago.

Venezuelan bondholders have also been busy working towards a resolution through the years in default limbo. Some have coalesced around the Venezuela Creditor Committee, which represents about $11bn out of the almost $60bn in face value. With a smattering of other friendly bondholders they represent about $20bn of Venezuelan debts.

Last autumn VCC struck an agreement with both Venezuela’s government and opposition — with the blessing of a New York court — that discarded any litigation and instead put the onus on a negotiated settlement with Caracas. The funds pursuing a strategy of suing are negligible in comparison.

Western-based bondholders were also effective in lobbying to end a secondary-market trading ban. They argued that barring US citizens from buying Venezuelan bonds punished them and merely rewarded “nefarious players” that weren’t affected by the sanctions.

Next on their target could be the primary market ban. After seven years, it makes little strategic sense to deny Venezuela a restructuring deal, especially as energy companies like Chevron are recouping their liabilities through oil-for-debt swaps.

The hedge fund Greylock Capital — co-chair of the VCC — has been particularly active in trying to bring about a restructuring deal. It wants to repeat the oil-based warrants that Suriname used to sweeten its 2023 restructuring.

In return for a 25 per cent debt haircut, Suriname’s bondholders will get a 30 per cent cut from the royalties from one of the country’s oil block (after the first $100mn a year that goes to the government) until the restructured bonds are repaid.

Greylock president Ajata Mediratta was one of the architects of that deal, and says that he had Venezuela in mind when devising it (Venezuela’s oil industry is not what it once was but it still has reserves of 300 billion barrels).

Sweeteners like this — often called value recovery instruments — are controversial. But Mediratta argues that warrants have usually been based on GDP growth, which has many drawbacks.

GDP is a theoretical construct to begin with, frequently revised in subsequent quarters and, every other decade, completely rebased. This makes it extremely difficult to model and virtually all these instruments have traded well below their theoretical value, disappointing issuer and creditor alike.

Mediratta also argues that any oil warrants will trade better than GDP warrants, since the royalties come off the top of the government’s revenue waterfall, as opposed to the GDP warrants. This could enhance transparency and make corruption and fiddles more difficult.

However, before anything like this can even be contemplated, Venezuela needs the US to relax its sanctions. Maybe the presidential election in July will prove a turning point?