This article is an onsite version of our Europe Express newsletter. Premium subscribers can sign up here to get the newsletter delivered every weekday and Saturday morning. Standard subscribers can upgrade to Premium here, or explore all FT newsletters

Good morning. A scoop to start: Europe has just 5 per cent of the air and missile defence systems that Nato has calculated are necessary to defend its eastern flank from invasion, in a stark illustration of the continent’s need to ramp up its military capabilities.

Today, I preview talks among Nato’s foreign ministers on the structure of future support for Ukraine, and Laura reports that many European countries are failing to police political corruption.

Podcast: How much power can far-right parties win in Europe? Gideon Rachman and I talk about next week’s European parliament elections: While far-right parties are set to win more seats, how will this translate into their ability to influence policy?

Bridging gaps

Should Nato take on the role of co-ordinating military supplies to Ukraine, and auditing its members’ promises? That’s the question occupying the alliance’s foreign ministers.

Context: Nato has proposed to take control of the currently US-led Ramstein group that has managed much of the western military support to Kyiv to defend against Russia’s invasion. It has also suggested setting an overall long-term spending commitment to support Ukraine, pegged by some at $100bn.

Ministers gathering in Prague today for two days of meetings are haggling over the benefits — and the potential details — of both, with a looming deadline of the alliance leaders’ summit in Washington on July 9.

Many see the benefits of “institutionalising” the Ramstein structure under Nato, rather than relying on the US to manage the entire process.

But some are sceptical about the financial pledge, arguing that it would in practice only duplicate bilateral and EU-managed commitments and not actually represent fresh cash.

Proponents see it as a way to ensure all countries pay their fair share, with a formula based on GDP, or the coefficients used to calculate contributions to Nato’s own budget. Opponents aren’t keen on some Nato suits with spreadsheets checking deliveries against promises.

“Given all the existing work inside the alliance, there is a question about whether or not we need someone here [in Nato] managing all of those workstreams,” Julianne Smith, US ambassador to Nato, told reporters yesterday. “Plus we are looking at ways to identify and secure more resources for our friends in Ukraine.”

But the biggest issue is that the proposed reshaping of military aid likely won’t satisfy Ukraine, many admit. Kyiv instead hopes for progress on its Nato membership in Washington, something the alliance says is not happening.

Ukraine was “not super thrilled” at the alternative offer, said one Nato diplomat, “but we are trying to tell them it adds value to the co-ordination of their supplies.”

“The intention is good . . . But Nato would not be adding much,” the diplomat said. “[The $100bn] would not be fresh money.”

Smith said the package of support would “in essence serve as a bridge to membership . . . that bridge will be well-lit and made of steel”.

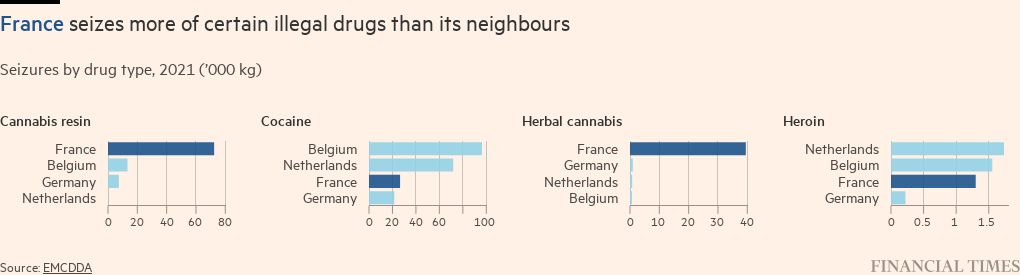

Chart du jour: French connection

Belgium is not the only European hub for drugs trafficking. Drugs-related homicides have reached unprecedented levels in Marseille, where the usage and supply of cocaine and top-selling cannabis have risen.

Grecommendations

With every new corruption scandal, voices grow louder against bribery and illicit influence in politics. But an international assessment has found that European countries still don’t do enough to actually fight corruption, writes Laura Dubois.

Context: The Group of States against Corruption (Greco), which consists of 46 European countries plus the US and Kazakhstan, since 1999 gives recommendations on fighting corruption and assesses whether countries actually implement them.

The Greco’s latest report published today finds that many countries fall short particularly when it comes to rules for parliamentarians and other top politicians.

“What we are seeing is a decrease of the implementation when we are talking about politicians, particularly parliamentarians and the government . . . top executive functions,” Greco president Marin Mrčela told the Financial Times.

“This is a particularly sensitive area because those people should lead by example,” Mrčela said, adding that Greco for instance looks at whether countries have codes of conduct for politicians, or whether they have to declare their assets or gifts they receive.

Countries fared better at implementing recommendations for law enforcement, judges and prosecutors, Mrčela said.

Some 10 countries — including Denmark, Italy and Poland — are falling short particularly on the recommendations for parliament, according to Mrčela. Finland and Norway are among the positive examples, which have implemented Greco’s recommendations in most areas.

Mrčela also urged the EU to become a member of Greco. “If they are not [a] full member we cannot monitor anti-corruption standards regarding the institutions of the EU, which of course looks odd.”

Case in point: Yesterday, Belgian authorities raided the European parliament over an alleged Russian corruption case.

What to watch today

-

Nato foreign affairs ministers meet in Prague.

-

EU energy ministers meet.

-

EU trade ministers meet.

Now read these

Recommended newsletters for you

The State of Britain — Helping you navigate the twists and turns of Britain’s post-Brexit relationship with Europe and beyond. Sign up here

Chris Giles on Central Banks — Your essential guide to money, interest rates, inflation and what central banks are thinking. Sign up here

Are you enjoying Europe Express? Sign up here to have it delivered straight to your inbox every workday at 7am CET and on Saturdays at noon CET. Do tell us what you think, we love to hear from you: [email protected]. Keep up with the latest European stories @FT Europe