A group of Winnipeggers are pitching the idea of creating a new national urban park that would cradle the meeting points of three rivers and encompass an area larger than Vancouver’s Stanley Park.

“Rivers are where our collective memories, desires and aspirations meet. Our proposal is simple: now is the time to protect Winnipeg’s rivers in perpetuity,” Jean Trottier, project lead for the Little Forks proposal, said at an announcement Wednesday morning.

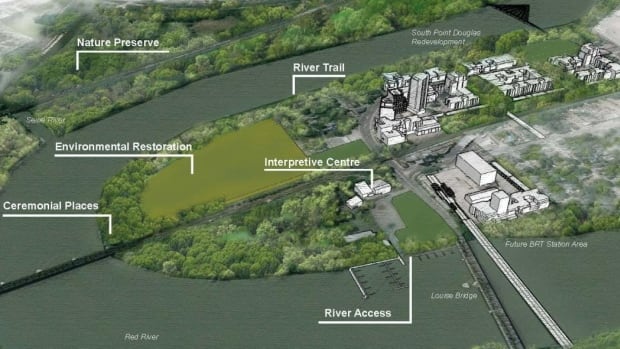

The park would be anchored at the tip of Point Douglas and extend north, south and west from there, taking in a large area where the Seine River empties into the Red River — known as petites fourchettes, or little forks, during voyageur days, Trottier said.

It would reach along the Red, Assiniboine and Seine rivers to encompass 430 hectares in the heart of the city.

Sel Burrows, a longtime Point Douglas advocate, said the seed of the idea was planted in 2009, when the North Point Douglas and South Point Douglas residents’ committees had a meeting with then-premier Gary Doer.

“We were talking about issues and in the middle of the meeting, he paused and said, ‘We really have to think about the point in Point Douglas. Why don’t we make it a provincial park?'”

Not long afterward, Doer stepped down to become Canada’s ambassador to the United States, a role he held until 2016.

The park idea went dormant until the Liberal Party made its a promise in 2021 to establish at least one new national urban park in every province and territory, with a target of establishing 15 national urban parks by 2030.

Trottier, an urban planner and associate professor in the department of landscape architecture at the University of Manitoba, wrote an article for the Globe and Mail in April 2022, saying those parks must be ambitious in their scope.

Burrows saw the article and contacted Trottier, and from there, a group was formed to pursue the idea.

“It’s happening, and this can be a major change for the inner city,” Burrows said.

From Point Douglas, Little Forks would go north along the Red River to St. John’s Park and south along the Seine to the Trans-Canada Highway. It would also head west and south along the Red to The Forks, and west from there along the Assiniboine River to the Osborne Bridge.

“The full extent of the park would comprise 430 hectares of land and water areas, more than three times the size of Assiniboine Park, twice the size of Montreal’s Mount Royal Park and larger than Vancouver’s Stanley Park,” Trottier said.

Nature preserves would be created, along with recreational trails.

“We also envision ceremonial and gathering places throughout the whole extent of the [national] park,” Trottier said, and the park would preserve places of historical significance to First Nations and Métis people.

The central location of the park would ensure easy public transit access while also putting it within a 10-minute walk for 12 per cent of the city’s population, including 18,000 Indigenous people, Trottier said.

A decline in industrial use, which dominated the point of Point Douglas for decades, “presents us with a unique historical opportunity,” Trottier said.

The park would heal damaged land and restore ecologically strategic but degraded sites. It would restore more than 14 hectares of former industrial land and add 85,000 trees, he said.

Making it a reality, however, will require a joint ownership and management agreement between many levels of government, private land owners, and Indigenous and community organizations, Trottier said.

The environmental restoration of degraded sites will take decades of sustained commitment, but it is entirely possible, he said, pointing to the transformation of the former railway yards at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine into one of Winnipeg’s premier gathering places, The Forks.

“Like our forebears, who created Winnipeg’s parks system, the floodway and The Forks, let us be visionary, bold and optimistic so future generations can look back and say this was the right idea at the right time,” Trottier said.

“We hope that the citizen-led initiative presented here this morning will prove compelling enough to rally us all around a common effort.”

The group did not have a cost estimate, but Doer, who attended Wednesday’s event, said the initial cost of The Forks was $21 million. It opened in 1989 and is 25 hectares in size.

“This is not going to be a slam dunk. I remember The Forks discussions [and] everybody had an opinion. Years later, when I meet my friends and they’re having people in from outside of Winnipeg, where do they take them? They take them to The Forks,” Doer said.

“I am confident we can land this project. It started with the community and it will land with the community. This is going to happen.”

There is no timeline on when the proposal must be submitted or when the federal government will make a decision.

“Parks Canada is really beginning this process right now,” Trottier said, noting he has met with Treaty 1 First Nations and the Manitoba Métis Federation.

“It’s going to take a bit of time to get everybody to come around the table … and eventually begin.”