Educators warn AI must be a teaching — not a cheating — aid

Artificial intelligence is rapidly transforming classrooms worldwide, as pupils adopt AI chatbots as a powerful research tool, and educators use the technology to deliver engaging lessons and cut their administrative workload. But, as generative AI makes it ever easier to create convincing prose based on simple prompts, experts warn that some students may use it as a shortcut for writing notes and essays — compromising their learning and creating a cheating epidemic.

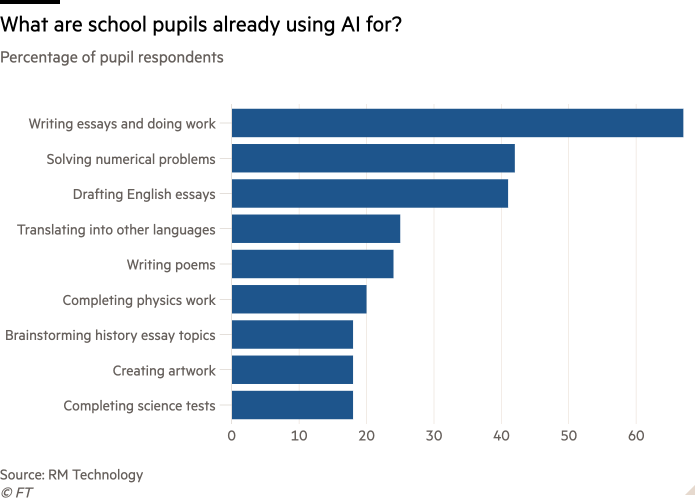

A 2023 study by edtech company RM Technology has already found that two thirds (67 per cent) of secondary school students admit to using chatbots such as ChatGPT for writing essays or doing work for them. They also said they were using AI for solving numerical problems (42 per cent), drafting English essays (41 per cent), translating text into different languages (25 per cent), writing poems (24 per cent), completing physics work (20 per cent), brainstorming history essay topics (18 per cent), creating art (18 per cent), and taking science tests (18 per cent).

Two-thirds of respondents in the RM Technology study also said AI usage has improved their grades.

However, while this level of usage is making the likelihood of AI-plagiarised essays and assignments a growing concern for teachers, not every student is using the technology in these ways.

For example, 17-year-old student James, from Ottowa in Canada, uses ChatGPT to provide more context on different topics and find reading materials. This makes it easier for him to plan, structure and compose his essays. He does not rely on AI to write entire assignments without his input.

Similarly, in maths, James uses AI bots to help get himself started: “The newer models have better visual capabilities, so I’ll send screenshots of problems and ask how I would solve them step by step to check my own answers.”

Emily, a 16-year-old pupil at Eastbourne College in southern England, adopts much the same attitude to using AI for schoolwork. She says: “The main way I use ChatGPT is to either help with ideas for when I am planning an essay, or to reinforce understanding when revising.”

Others, though, are more cavalier in their approach to AI.

Fiore, a 17-year-old student from Delaware in the US, has used ChatGPT to generate several entire essays when deadlines were nearing or if they required information that he did not have. He accepts that this is “cheating” and potentially making him “lazier”, but his teachers have not caught him yet.

“I use ChatGPT mostly on English assignments, especially large ones — I started doing this around last year,” he says. “I still use AI because of its ease of use. All I really need is the grade for the class, and that’s it.”

There may even be other benefits to letting AI take the strain: in a poll of 15,000 American high school students, conducted by AI-powered educational platform Brainly, 76 per cent said the tech could decrease exam-related stress, while 73 per cent said it could make them more confident in class.

But, with so many pupils using AI in different ways, Adam Speight — an acting assistant headteacher based in Wales and a writer at educational resources provider Access Education GCSEPod — says it is essential that teachers also educate themselves on appropriate uses of the technology.

“AI can speed up the research process for both learners and educators,” he suggests. “What is cheating is when a learner has used AI to do all their work for them.”

Speight says teachers should always “question the validity” of their students’ assignments. He adds that any concerns — and the consequences of cheating — should then be clearly communicated with the student.

Gray Mytton, assessment innovation manager at qualification awarding body NCFE, argues that the fair use of AI will vary by learning outcomes. “For example, if spelling and grammar is being assessed, then learners can’t demonstrate this independently if they are using AI to alter their spelling and grammar,” he explains.

“On the other hand, if a learner is tasked with creating a marketing video, then using AI to create ideas to enhance video flow could be considered fair use, because the learner is applying these ideas to their video product — but not if the intended learning outcome is to understand different methods of improving flow in a video.”

Jane Basnett, director of digital learning at Downe House School in Berkshire, reckons the rise of AI has “exacerbated” the problem of plagiarism. “Students have always found ways to outwit the systems designed to ensure academic integrity, and the temptation to resort to AI to complete assignments is strong,” she says.

Despite these concerns, though, teachers can demonstrably benefit from employing AI.

Sharon Hague, managing director of school assessment and qualifications at academic publisher and awards body Pearson, says AI could help the teaching workforce free up “hundreds of thousands of hours per week” spent planning lessons and performing other administrative work by 2026. That would allow teachers to “work more directly with students”.

73%Proportion of American high school students saying AI could make them more confident in class

She warns, however, that they need to strike a balance between AI usage and manual work. “Teachers tell us that lesson planning and marking, for example, are often helpful processes . . . to go through themselves.”

When in the classroom, the technology then provides ways to increase the personalisation and creativity of lessons, reckons Jason Tomlinson, managing director of edtech firm RM Technology. He uses the example of an IT teacher explaining “complex concepts” as “digestible formats” that resonate with students, such as “in the tone of their favourite superhero”.

Rory Meredith, director of digital strategy and innovation at South Wales-based further education provider Coleg y Cymoedd, says teachers can then use the data provided by AI systems to track their students’ progress and, if needed, implement targeted interventions. He likens AI to a satnav for “monitoring and recording a learner’s learning journey from point A to B.”

And, when students reach point B, they will need to be able to demonstrate a range of AI skills as so many employers now expect school leavers to possess them. Chris Caren, chief executive of plagiarism detection software Turnitin, says companies are increasingly looking for people who can use AI to “help with writing” and “drive efficiency” in their day-to-day roles.

The risk, here, is that school leavers abuse the technology to inflate their grades on fake CVs and get chatbots to write unauthentic cover letters. Stephen Isherwood, joint CEO of the non-profit professional body Institute of Student Employers, points out that employers are “very aware” of this problem and, consequently, are implementing guidelines defining correct and incorrect AI usage.

Such abuses of AI will not help students in the long run, however. “When an employer meets a student in person, they may not demonstrate the kind of behaviours they expected from the application,” Isherwood points out. “Worst-case scenario is someone gets a job and then finds they can’t do it or it isn’t suited to them.”

John Morganelli Jr — director of college admissions at New York-based private tuition company Ivy Tutors — says some students will want to use AI in their applications so as not to be “at a disadvantage”. But he thinks employers will be wise to it.

“Over time, I believe that admissions officers and hiring managers may place greater emphasis on real-time assessments, such as interviews or video portfolios, to gauge a candidate’s true abilities,” he says. “This shift might lead to more innovative interview formats, where candidates face questions generated by AI without prior knowledge of the topics.”