As McKinsey’s 3,000 partners gathered this week in Copenhagen for their first in-person meeting in two years, the firm’s leadership was projecting a positive message and pointing to a consulting market that appears to be picking up after more than a year of sluggish growth.

The mood in the halls was somewhat more nuanced, however, because an upturn has not come soon enough to prevent another big push to cut staff numbers across the 45,000-person firm.

McKinsey is in the middle of a brutal round of career reviews, according to people familiar with the process. Its consultants will all be graded this month and those deemed to be underperforming will be — in McKinsey parlance — “counselled to leave”.

In the past few years, these mid-year performance reviews have been something of an informal catch-up with managers, much less significant than the year-end reviews that take place around October. The return to a formal grading system at the halfway point of the year is a way to speed more staff towards the exits, the people said.

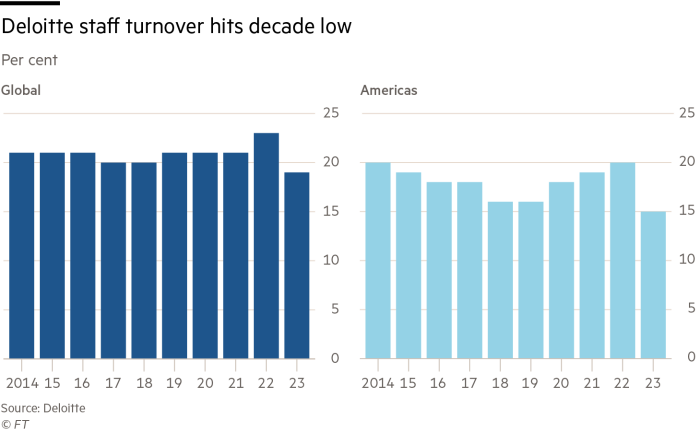

Two years on from the Great Resignation, when a roaring jobs market and the effects of the pandemic encouraged swaths of the workforce to switch employers, the situation could not be more different. In the professional services, the numbers leaving firms of their own accord have swung to historic lows, as tech groups, investment banks and other destinations have gone from hiring mode to firing mode. Bosses of consulting and accounting firms have been desperate to increase what they call “attrition”.

At McKinsey, in recent weeks, this has taken a variety of forms. Mid-level staff have been offered financial incentives to leave: nine months’ pay while they look for another job. Others have simply been laid off: up to 400 jobs were axed this month in specialist areas such as data and software engineering.

Bob Sternfels, McKinsey’s global managing partner, signalled the firm would be “back in balance” by the end of this year, according to people familiar with his message, implying more large-scale departures. One person said the percentage of McKinsey consultants who leave in a typical year is about 20 per cent, but in 2023 it slid to 15 per cent.

A return to normal cannot come soon enough for senior partners whose profits have been held back by the cost of all these unwanted salaries.

“We somehow stopped the meritocracy,” said one former McKinsey partner who remains close to the firm. “We stopped pushing people to leave and had an enormous overhang of people. When that happens the numbers just get staggeringly bad. Don’t we advise companies on this?”

The sharp decline in attrition is a phenomenon across professional services firms and around the world, compounding the effect of a slowdown from the post-pandemic boom in advisory work on digital services and mergers and acquisitions.

Deloitte publishes a staff turnover figure in its annual report, which last year showed departures at their lowest level in a decade both globally and in the Americas. KPMG noted “capacity issues created by ongoing and historically low attrition” when it cut jobs in its US audit business in March. Bain also cited lower attrition when offering some consultants in London redundancy with six months’ pay, partly paid temporary leave, or an option to relocate to one of the firm’s offices abroad.

Most accounting and consulting firms have conducted lay-offs, pushed greater numbers out through the performance review process, or created voluntary schemes to encourage people to leave — and usually a combination of all three.

Some appear to have acted earlier and more forcefully than others. In contrast to the sharp drop at McKinsey, attrition at rival BCG was in line with the 12-year average last year, according to people familiar with statistics circulated internally. But that was achieved via a notable shift. In the eight years from 2012 to 2020, voluntary attrition was about half of the total at BCG, while in 2023 it was only one-third. In other words, two-thirds of those who left had been told to go.

“We hire exceptional people with a promise of enormous personal growth, substantial development opportunities, and a very honest culture around feedback,” said Rich Lesser, BCG’s global chair. “If that’s what you’re offering, then you have to aim for consistency in promotions and attrition, which we’ve worked hard to deliver over many years.”

He acknowledged the “emotional reality” of the swing from voluntary to involuntary attrition. “The job market for BCG-type talent was very robust in 2021 and 2022,” he said. “It was much less so in 2023. So, for anyone departing, that wasn’t easy.”

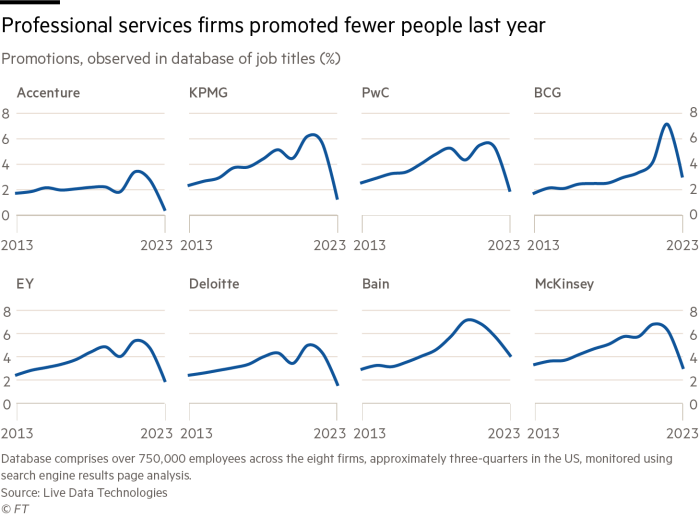

A slump in voluntary departures is a challenge to professional services firms’ traditional “up or out” model. Less “out” means less “up”, a phenomenon suggested by data from across the sector.

Live Data Technologies, which tracks the job titles of millions of white-collar workers, observed many fewer promotions in 2023 than in the previous year at consulting and accounting firms. At Bain and BCG, the proportion of staff spotted making upward moves was back down to pre-pandemic levels; at McKinsey it was below anything seen in at least 10 years.

“It is more difficult to get promoted,” said Namaan Mian, chief operating officer of Management Consulted, which coaches students through the consulting firm recruitment process. “The performance reviews are getting tougher, and more of the work is going to top performers. Low and medium performers are spending more time ‘on the beach’ [without projects to work on], which means they are not getting visibility internally, they are not learning.”

Surveys point to better growth for the consulting sector this year. “While far from a return to the prior bull market in professional services, many firms headed into 2024 with greater confidence that revenue targets could be met, now that most have accepted the gold-rush years of 2020-2022 were outliers and not the new normal,” Adam Prager, co-head of the recruitment firm Korn Ferry’s professional services practice, wrote in a report last week.

It could take until 2025 for hiring, firing and promotions to settle back into their pre-pandemic patterns, however, said Mian. “We can see the light at the end of the tunnel,” he said, “but we are not out the tunnel yet.”