This article is an on-site version of our Moral Money newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox.

Visit our Moral Money hub for all the latest ESG news, opinion and analysis from around the FT

BlackRock’s Larry Fink yesterday issued his annual letter to investors — days after news that investment funds in Republican states have pulled $13.3bn from the world’s largest asset manager. Although the withdrawals add up to roughly 0.1 per cent of BlackRock’s assets under management, Fink was at pains to stress he’s no eco-fanatic. Instead, he’s urging “energy pragmatism”. Read our colleague Brooke Masters’ full run-down here.

Meanwhile, in today’s newsletter, we look at a new push to put agricultural waste to profitable use. Much-hyped efforts to make biofuels from it in the 2010s didn’t really take off. Now, start-ups want to use this waste in systems to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere permanently.

As we noted in a recent edition, carbon removal will be a crucial part of the global push for net zero emissions, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. But if biomass-based schemes are to play a major role, they will require close monitoring of land management in far-flung regions. As the proverb goes, the mountains are high and the emperor is far away.

Thanks for reading.

carbon removal

What will the next biomass rush look like?

Biomass has had many false dawns. As we enter another boom period, the newest wave of entrants, many of which have close links to the tech sector, have converged on a new use case: carbon dioxide removal.

Instead of processing corn, wood or other plant matter into a value-added commodity, these start-ups are competing to build businesses that lock it away to stop it giving off greenhouse gases.

Frontier, a coalition of tech companies paying a premium to accelerate promising carbon solutions, has backed several of the start-ups — including Charm Industrial, founded in 2018.

Crops such as corn pull carbon out of the atmosphere while growing — but then release much of it after a harvest, as stalks and husks, for example, remain on the field and decompose. Charm uses portable pyrolysers — essentially, oxygen-free ovens — to convert this waste into a carbon-rich “bio-oil”.

Charm’s original plan was to use this oil to make hydrogen, co-founder and chief executive Peter Reinhardt told me, but that application proved “economically uninteresting”. Instead, Charm has developed a method to store bio-oil underground, where it will stay sequestered for at least 10,000 years, according to the company.

The US is littered with more than 100,000 abandoned oil and gas wells, many of which leak toxic chemicals. Charm’s idea is to pump bio-oil into those wells for long-term storage, and sell corresponding carbon credits to corporate buyers. Bio-oil is corrosive, so in addition to applying for permits, Reinhardt told me, the company has had to overcome engineering hurdles.

Still, Charm’s system is up and running, albeit at modest volumes. In the three years after it started bio-oil storage in 2020, Charm says, it sequestered about 6,400 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent — roughly equal to the annual emissions of 430 US residents. Frontier, at least, is sold: last year, the tech initiative signed a $53mn long-term offtake agreement to buy credits from Charm.

Growing responsibly

There are potential risks to the biomass rush, said David Keith, a climate scientist and policy expert at the University of Chicago who founded the rival carbon removal company Carbon Engineering. Payment for corn waste increases the profitability of corn farming, Keith argued, potentially incentivising more production of the crop, with negative environmental effects.

Beginning in 2005, US biofuel policy catalysed a major expansion of corn cultivation that drove changes in land use, leading to impacts such as soil erosion and phosphorus run-off, according to a 2022 paper in the scientific journal PNAS. Reduced rates of cropland retirement and the increased application of nitrogen fertilisers raised carbon emissions, the study found.

An earlier paper looked specifically at the impact of corn stover — that is, the leftover of the corn harvest — and found that stover harvesting could make farming corn more profitable. In turn, that could intensify corn farming practices, with impacts on soil and fertiliser use.

Isometric, a carbon removal standard and registry that Charm works with, aims to address that problem in its guidelines. For example, it says Charm should not source corn by-product from the same field two years in a row. That’s to avoid encouraging farmers to change crop rotation practices, in ways that could harm the health of the soil.

I asked Reinhardt whether he worries that the basic economics of paying for waste could drive land use change. “Not at the scale we’re at now. There are much bigger drivers of [crop] rotations,” he told me. “There’s some de minimis, incremental impact.”

Charm’s impacts may be minimal in this early phase, but the goal of Frontier is to help promising technologies take off. If companies such as Charm grow substantially, they could put upward pressure on a tightening market, according to Rudy Kahsar, who leads the carbon removal team at climate consultancy RMI.

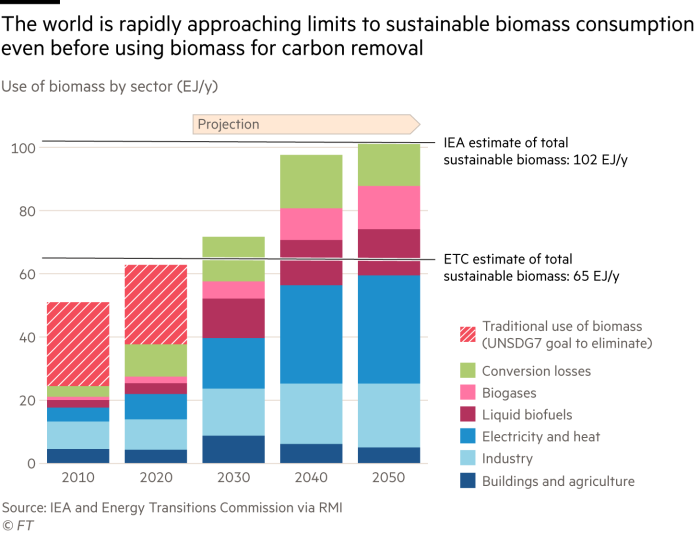

Plant-based carbon removal companies were “all competing with each other for the same biomass”, Kahsar said. Experts disagree on exactly what quantity of global consumption of biomass would be sustainable, without harming biodiversity and soil carbon stock. But, he said, “we’re bumping up against that” level.

The International Energy Agency has said that the maximum sustainable level of biomass consumption, which does not include biomass consumed as food, is around 102 exajoules per year. The IEA projects that the world will be approaching that level by 2040 — even without including the production of biomass used for carbon removal.

Plants in high demand

Carbon sequestration companies are not the only ones jostling to source plants for clean-tech projects. A new crop of start-ups, such as Houston-based Solugen, are attempting to make petrochemicals from plants, replacing fossil inputs to the refining process, such as propane and ethane, with plant feedstocks like corn sugar.

In the western US, there’s also a growing effort to use the wood from forest thinning — removing trees and undergrowth to reduce wildfire risk — as carbon removal feedstock. Charm had already tapped into this “wildfire fuel reduction” industry, Reinhardt said, using wood cleared from forests for carbon sequestration.

Kodama Systems, another Frontier-backed start-up that has raised money from Bill Gates’s Breakthrough Energy Ventures, makes safe forest management a central part of its business pitch. The company plans to store wood chopped down from California’s forests in vaults designed to contain greenhouse gases.

Part of Kodama’s pitch is that it is developing technology to automate the more repetitive parts of thinning operations, making the human workforce more productive as demand for forest management grows.

As with agriculture, however, the test of the business will be whether it can expand responsibly. More companies were competing for a limited supply of biomass, Kahsar said. “Maybe you can find some extra waste to turn into bio-oil and sequestration that in Kansas,” he added. “But if you try to scale any of those approaches, you’re probably going to run into feedstock challenges.”

Smart read

Iceland plans to plant more corn and rein in its bitcoin miners, Andy Bounds and Alice Hancock report, as the government aims to cut reliance on food imports and free up its supply of renewable electricity by energy-hungry cryptocurrency groups.

Recommended newsletters for you

FT Asset Management — The inside story on the movers and shakers behind a multitrillion-dollar industry. Sign up here

Energy Source — Essential energy news, analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here