Human activities are merging global ant populations, eroding natural evolutionary distinctions and threatening biodiversity, especially in tropical regions and on islands.

Human activity is leading to the global redistribution of ants, with a new study in Nature Communications from the Department of Ecology and Evolution at UNIL highlighting how this shift is altering ant communities worldwide. The research emphasizes that human influence is disrupting biodiversity and biogeographical patterns that have evolved over millions of years, with a particularly pronounced effect on tropical regions and islands.

Picture yourself with your feet in the sand, relaxing on a beach to the north-east of Bali. Ahead lies Lombok, its silhouette visible against the horizon. Tomorrow, you plan to cross the 40 kilometers separating these two islands in the vast Indonesian archipelago. Unbeknownst to you, this journey will carry you across an imperceptible boundary: the Wallace Line.

This invisible demarcation results from the past movement of tectonic plates, ancient climates, and millions of years of evolutionary processes, dividing the biogeographic realms of the Indomalayan and Australasian regions. Discovered nearly 170 years ago by the intrepid British naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, this line once promised a stark juxtaposition of Lombok’s flora and fauna against its neighboring Bali. Yet, amidst the complexities of contemporary ecological dynamics, one must ponder: does this demarcation still hold true today?

Cleo Bertelsmeier, Lucie Aulus-Giacosa, and Sébastien Ollier, respectively associate professor, post-doctoral researcher, and biostatistician in the Department of Ecology and Evolution in the Faculty of Biology and Medicine at UNIL, have studied the impact of the human-mediated dispersal of non-native species on these natural biogeographical barriers. Through a study focusing on ants as a prime example, the researchers highlight the impacts of 309 non-native species, primarily transported by accident through the global exchange of commodities and tourism. Their findings unveil a profound alteration in the historical distributions of ant species, underscoring the far-reaching consequences of human activity on our ecological landscapes.

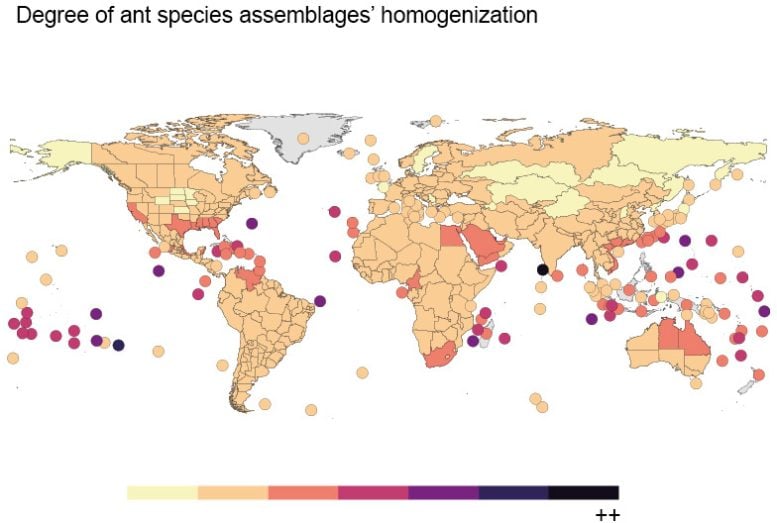

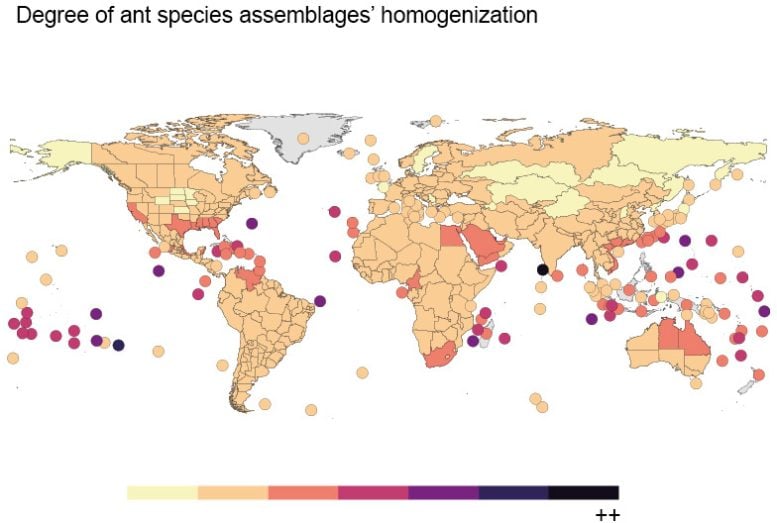

Compared with the continents, the homogenization of ant assemblages is particularly marked on islands, which are home to some rare and particularly vulnerable ecosystems. Credit: Lucie Aulus-Giacosa, DEE-UNIL

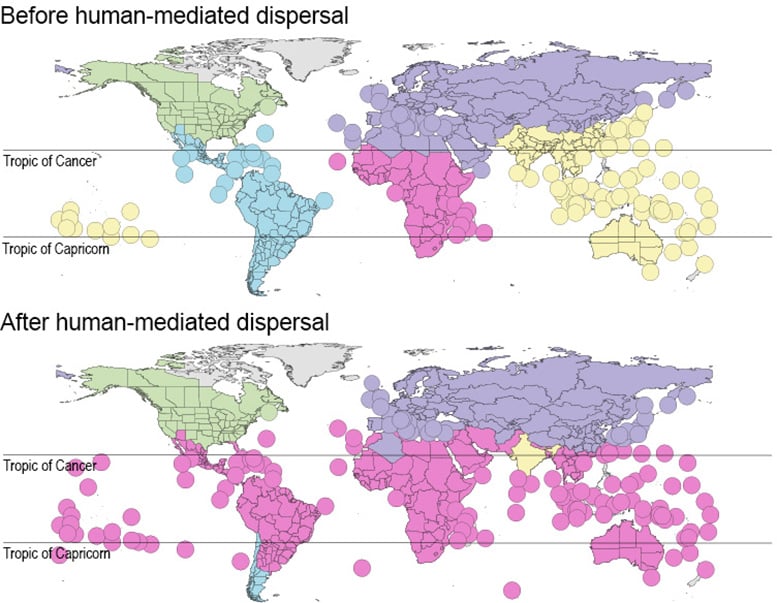

The dispersal of 309 non-native ant species has had a major impact on the biogeographical patterns of all 13,774 ant species with known distributions, with the emergence of a single bioregion in the tropics consisting of similar species assemblages. Credit: Lucie Aulus-Giacosa, DEE-UNIL

“Investigations into the impact of non-native species on biogeography have predominantly focused on gastropods in prior research. However, our study breaks new ground by focusing on ant species that are insects, a taxonomic group estimated to encompass a staggering 70% of the Earth’s living animal mass,” remarks Lucie Aulus-Giacosa, the lead author of the recent publication in Nature Communications. “Furthermore, our findings reveal a pivotal insight: the profound changes induced by non-native ant species extend far beyond the distribution patterns of the 309 ants we analyzed. Rather, they exert a transformative influence on the entire bioregional structure of ant biodiversity, encompassing the 13,774 described species with known distributions.” A mere 2% of these species’ movements suffice to erode established borders and redraw the distribution map for this diverse array of insects, underscoring the magnitude of our impact on global ecosystems.

Homogenization in the tropics…

In practical terms, almost all the territories located under the Tropic of Cancer now form a single biogeographical area made up of similar species (see main image). “Simply put, whether you’re exploring the landscapes of Australia, Africa, or South America, encountering the same ant species is now highly probable.” elucidates Cleo Bertelsmeier, the project’s director. “Such a phenomenon would undoubtedly give pause to Wallace himself!”

The authors attribute this phenomenon to the exceptional faunal diversity found within the tropics. Consequently, species inhabiting these regions are not only more likely to be inadvertently transported but also to successfully establish themselves in similar tropical climates elsewhere. “It’s deeply disconcerting to acknowledge that within a mere 200 years of human influence, we’ve managed to completely overhaul patterns shaped by 120 million years of ant evolution,” remarks Cleo Bertelsmeier, underscoring the profound implications of our ecological footprint on Earth’s biodiversity.

Compared with the continents, the homogenization of ant assemblages is particularly marked on islands, which are home to some rare and particularly vulnerable ecosystems. Credit: Lucie Aulus-Giacosa, DEE-UNIL

… and on islands

Broadly, the study underscores a concerning trend: 52% of ant assemblages worldwide have undergone increased similarity, reaffirming the pervasive phenomenon of biotic homogenization at the global scale. Notably, this homogenization disproportionately impacts tropical regions, with islands bearing a particularly heavy burden. Given their rich evolutionary legacies, these locales harbor distinct ecosystems highly susceptible to human pressures. Consequently, there’s a palpable apprehension that endemic species may face the perilous brink of extinction.

Specializing in the spread of invasive insects in connection with the globalization of trade and human mobility, the authors are now planning to deepen their investigation into island regions. “Given their geography, they attract more tourists, and they import more foodstuffs. But these often arrive accompanied by undesirable guests that are potentially harmful to the local fauna and flora, which are particularly fragile. For example, we would like to understand whether this phenomenon explains why homogenization is more marked on certain islands”, explains Lucie Aulus-Giacosa.

Reference: “Non-native ants are breaking down biogeographic boundaries and homogenizing community assemblages” by Lucie Aulus-Giacosa, Sébastien Ollier and Cleo Bertelsmeier, 13 March 2024, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-46359-9