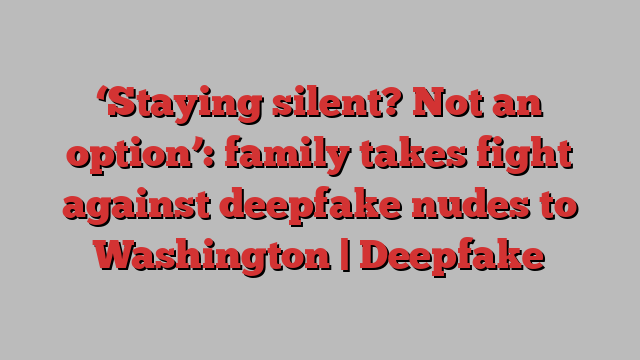

‘Staying silent? Not an option’: family takes fight against deepfake nudes to Washington | Deepfake

In October last year Francesa Mani came home from school in the suburbs of New Jersey with devastating news for her mother, Dorota.

Earlier in the day the 14-year-old had been called into the vice-principal’s office and notified that she and a group of girls at Westfield High had been the victims of targeted abuse by a fellow student.

Faked nude images of her and others had been circulating around school. They had been generated by artificial intelligence.

Dorota had been tangentially aware of the power of this relatively new technology, but the ease with which the images were generated took her aback.

“I didn’t know how quickly it could happen, with just one image,” she recalled. “That it can happen to anyone, by anyone, with the click of a button.”

According to a recently filed federal lawsuit filed by a different family, the explicit images at Westfield High were created via the use of an app named ClothOff, which has operated under a deep layer of secrecy.

But a six-month investigation, part of the Guardian’s podcast series called Black Box, has revealed the names of several people affiliated with the app, which receives millions of monthly visits, tracing its origins to Belarus and Russia.

As the shock on that October afternoon subsided, Francesca Mani wiped away tears and decided she would take action by going public. The mother and daughter were dissatisfied with their school board’s response, and disappointed that, because no laws existed, it was unlikely the alleged perpetrators would be held criminally responsible.

“I need to do something,” Francesca told her mother. “This is not OK and I will not be a victim.”

The pair have since made a number of trips to Washington, including to the State of the Union address last week. They have appeared on cable news together and been cited by lawmakers in both New Jersey and in DC as catalysts for new legislation to hold creators of non-consensual, sexually explicit deep fakes legally accountable in the US.

The case in Westfield, and others like it, have exposed growing gaps in federal and state laws that legislators on both sides of the political aisle agree do not do enough to protect people, particularly minors, from the rapid proliferation of explicit AI deep fakes.

“There is a unique danger around these apps,” said Yiota Souras, chief legal counsel with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children [NCMEC]. “Because the volume of victims they can create in a very short time is immense.”

NCMEC has been working directly with the Mani family as they attempt to see if any of the images generated at Westfield High have circulated further online.

Victims’ parents received assurances from school officials that the deep fakes had been deleted, but the school has not publicly stated how many students were affected.

The Westfield public school district said it commenced an investigation into the incident as soon as it was made aware and provided counselling to “students seeking support”.

“All school districts are grappling with the challenges and impact of artificial intelligence and other technology available to students at any time and anywhere,” said superintendent Dr Raymond González, who added that the district was continuing to strengthen efforts to prevent future incidents by “educating our students and establishing clear guidelines to ensure that these new technologies are used responsibly in our schools and beyond”.

ClothOff has denied its platform was used in the New Jersey case, and suggested it may have been a competitor app but provided no evidence to substantiate this claim.

Shortly after speaking out in public, the mother and daughter were invited to Washington to mark the introduction of a bill in Congress, the Preventing Deepfakes of Intimate Images Act.

The legislation seeks to prohibit nonconsensual disclosure of AI-generated images by making it a criminal offence to share them, as well as providing victims with rights to take civil action in federal court.

Dorota will visit the Capitol again this week for a subcommittee hearing on “addressing real harm by deep fakes”, while another bill, introduced by the Republican congressman Tom Kean Jr, who represents the family’s district, seeks to create labelling rules for AI content to make it easier to distinguish.

“Just because I’m a teenager doesn’t mean my voice isn’t powerful,” Francesca said as the legislation was unveiled in Washington. “Staying silent? Not an option.”

Both bills and their senate counterparts have bipartisan support, but with a House so focused on partisan issues, including impeachment inquiries pointed at the president, Joe Biden, Dorota Mani realises that lawmaking on the federal level is still in its infancy.

“Am I frustrated? No. Because that’s our government – it has always functioned that way,” she said. “That’s why I’m not a politician. That’s why this is my first and last campaign.”

Still, at least five US states have already enacted laws to curb the use of explicit deep fakes with about 20 introducing legislation, according to a database maintained by NCMEC.

In New Jersey, a bill introduced following the episode at Westfield High, cleared a senate committee last Friday with bipartisan support.

A Polish migrant, who came to the US for college in the 1990s, Mani is a wealthy entrepreneur who founded a local preschool academy and runs an interior design business. She also talks candidly about how financial privilege has helped her campaign, which has drawn bipartisan admiration in Congress.

A spokesperson for the New York congressman Joe Morelle, who introduced the Preventing Deepfakes of Intimate Images Act, said the mother and daughter had “taken their trauma and turned it into fierce advocacy to ensure more women do not have to suffer through the pain Francesca went through”.

The spokesperson added that recent reporting by the Guardian revealing some of the individuals associated with the ClothOff app “underlines why there must be both criminal and civil penalties to hold people accountable for this despicable behaviour”.

“We must establish strong deterrents to prevent people from creating deepfakes and certainly from profiting off of them.”

But the episode in New Jersey was far from isolated in the United States. Last week a middle school in Beverly Hills expelled five students who victimised 16 eighth-grade students by creating AI-generated deep fake explicit images. A spokesperson for the school board would not comment on which specific app was used to create the images.

“This emerging technology is becoming more and more accessible to individuals of all ages,” said Dr Michael Bregy, superintendent for the Beverly Hills unified school district.

“We are appalled by any misuse of AI and must protect the most vulnerable members of society, our children.”

In December of last year two male students at the Pinecrest Cove Academy were suspended after generating nude images of several classmates using an app unnamed by local police.

And in Issaquah, Washington a 14-year-old male student was investigated by police for generating nude photos of several female classmates using images he had taken at school events, later sharing them via Snapchat, according to a police report reviewed by the Guardian, which does not name the app in use.

Mani said she has heard from parents in many places around the country, including areas that had not been reported in the media.

“Many people don’t feel comfortable going public with what happened,” she said. “Because, just like in my school, they are constantly hearing that nothing can be done.”

Asked what her message would be to those behind the app reportedly used to target her daughter and her classmates, Mani was direct: “Shame on them. They’re just making money.”

But immediately, she pivoted to the next step in her campaign, to target platforms like Apple, Google and Amazon and the financial institutions such as PayPal, Amex and Visa that she said ultimately allowed such technology to prosper.

“Otherwise it’s like chasing ghosts.”