When New York Community Bank reignited concerns about US regional banks by revealing big losses from commercial real estate loans at the end of January, Steven Mnuchin spotted his chance to get back into the game.

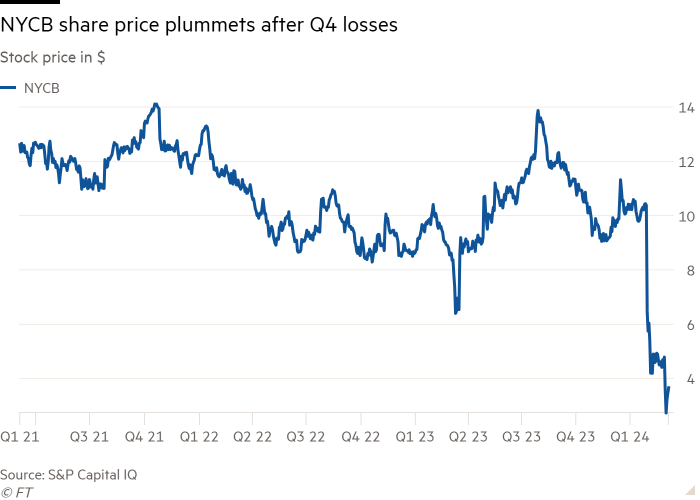

Donald Trump’s former US Treasury secretary had made a fortune rehabilitating a failed US mortgage lender after the 2008 financial crisis. This time, as NYCB’s shares plummeted 38 per cent in a day, Mnuchin put in a call into Jefferies, the mid-sized lender’s go-to advisers, to let them know that his private equity firm would be interested in throwing the bank a lifeline.

Just over a month later, NYCB turned to Mnuchin, 61, to anchor the $1bn equity injection that it announced on Wednesday.

NYCB is hoping the equity raise will stabilise the bank after it cycled through three chief executives in six weeks as its stock price plunged on worries about its commercial real estate exposure.

For Mnuchin, it is his highest-profile deal since leaving the Trump administration and one which investors hope will replicate his highly lucrative but controversial turnaround of failed US bank IndyMac 15 years ago. His consortium may have already struck gold — the paper gains on the transaction at Thursday’s closing price are about $1.2bn, according to Financial Times calculations.

“Steve’s a very careful investor, and I’m assuming that he did his homework,” Wilbur Ross, a private equity investor who worked with Mnuchin in Trump’s cabinet, told the FT. “This is a bank that he bought for an eighth or tenth of its top valuation. They can fix it and make it very healthy.”

NYCB and Mnuchin declined to comment. This account of how the deal came together is based on conversations with eight people familiar with the matter.

NYCB, more than a century old and based in Hicksville on New York’s Long Island, had become the 33rd biggest US bank by assets after almost doubling in size on the back of two quick-fire deals for Flagstar Bank and the rump of Signature Bank, which failed last March.

The Signature purchase was initially viewed as a sweetheart acquisition, helping NYCB’s stock almost double in a matter of months.

But NYCB would soon face concerns about a worsening credit environment for commercial real estate, where it had a large exposure, and fixed-rate loans that were yielding less than benchmark interest rates. The lender was also facing more stringent regulatory oversight because of its bulkier size following the Flagstar and Signature deals.

Things came to a head on January 31 when NYCB reported an unexpected loss from loans tied to office buildings and slashed its dividend. Almost a year on from the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, investors feared another regional US lender was in trouble.

Mnuchin is no stranger to a banking crisis. After 17 years at Goldman Sachs, he made his real fortune fronting a group in 2009 to acquire IndyMac, which now ranks as the fifth-biggest failed bank in US history. The acquisition was as lucrative as it was controversial.

OneWest, as IndyMac was renamed, made headlines for its hard-knuckled approach to evictions and debt collecting, foreclosing on tens of thousands of homes. But when it was eventually sold in 2015 to CIT, Mnuchin’s consortium of investors had more than tripled its money, including dividends paid along the way.

“They took a fairly cold-blooded approach when it came to foreclosures,” said Jesse Van Tol, head of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, which advocates for low and moderate income borrowers.

While Mnuchin’s first outreach to NYCB was unsuccessful, his chance came back around quickly. A week after January 31, former Flagstar CEO Alessandro DiNello took over as NYCB’s executive chair, in effect superseding chief executive Thomas Cangemi. DiNello had one message for the board: start planning for the worst.

Within days, DiNello and Mnuchin were on the phone, and the deal started moving forward, slowly at first. Mnuchin got access to NYCB’s loan files for due diligence, but DiNello was not ready to commit to a deal.

Then NYCB identified a weakness in its loan controls, telling the market on Friday March 1. Deposits, which had been stable for weeks, started leaving. Later in the day, Moody’s downgraded its credit rating for the bank’s deposits to junk.

DiNello, who by that time had formally replaced Cangemi as CEO, instructed Jefferies on Saturday morning to start canvassing potential investors with the initial goal of raising about $600mn to $700mn. In the end, it pulled in more.

It was clear from the start that Mnuchin’s firm, Liberty Strategic Capital, whose backers include SoftBank and Saudi Arabia’s sovereign wealth fund, would anchor the deal by putting in $450mn. Reverence Capital, an investment firm co-founded by fellow Goldman alumnus Milton Berlinski, would eventually put in $200mn.

Other investors included Hudson Bay Capital Management, which put in $250mn, and Citadel, the hedge fund led by billionaire Ken Griffin. By Tuesday Jefferies had commitments of about $1bn, with the deal to be priced based on the prevailing market price on the day it closes.

NYCB had hoped to announce the deal before the market opened on Wednesday but did not make it in time. At midday, the Wall Street Journal reported the bank was gauging investor interest in buying new stock.

This sent NYCB’s shares, which had been hovering above $3 a share, crashing below $2. Trading was halted as the bank rushed to get an official announcement out, misidentifying Citadel in its haste as Citadel Securities, the market making business. In the end, the investor consortium bought in at $2 a share, a slight premium to where the stock had been halted at.

But within hours the new investors were sitting on hundreds of millions of dollars of paper profits and NYCB appeared to have halted its freefall. By Thursday evening, Moody’s said it was reviewing whether to upgrade its credit rating.

Along with the equity raise, NYCB said Joseph Otting, a former US banking regulator who ran OneWest for Mnuchin, would take over as NYCB CEO. On Thursday morning, Mnuchin went on CNBC to promote the deal.

“Joseph and I have done this before with a bank that needs to be rebuilt,” he said. “We’ve got plenty of time over the next couple of years to really rebuild this franchise.”

Additional reporting by Sujeet Indap