Variability is crucially important for learning new skills. Consider learning how to serve in tennis. Should you always practice serving from the exact same location on the court, aiming at exactly the same spot? Although practicing in more variable conditions will be slower at first, it will likely make you a better tennis player in the end. This is because variability leads to better generalization of what is learned.

Chihuahuas and great danes

This principle is found in many domains, including speech perception, grammar, and learning words and categories. For instance, infants will struggle to learn the category “dog” if they are only exposed to chihuahuas, instead of many different kinds of dogs (chihuahuas, poodles and great danes).

“There are over 10 different names for this basic principle,” says MPI’s Limor Raviv, the senior investigator of the study published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences. “Learning from less variable input is often fast, but may fail to generalize to new stimuli. But these important insights have not been unified into a single theoretical framework, which has obscured the bigger picture.”

To identify key patterns and understand the underlying principles of variability effects, Raviv and her colleagues reviewed over 150 studies on variability and generalization across fields, including computer science, linguistics, categorization, motor learning, visual perception and formal education.

Mr. Miyagi

The researchers discovered that, across studies, there are at least four different kinds of variability, such as set size (e.g., the number of different examples or locations on the tennis court) and scheduling (e.g. practice schedules with different orders or time lags). “These four kinds of variability have never been directly compared, which means that we currently don’t know which is most effective for learning,” says Raviv.

The impact of variability depends on whether it is relevant to the task or not (arguably, the color of the tennis court is not relevant to serving practice). But according to the “Mr. Miyagi principle” (inspired by the 1984 classic movie “The Karate Kid”), practicing seemingly unrelated skills (such as waxing cars) may actually benefit learning of other skills (such as martial arts).

Competing theories

But why does variability impact learning and generalization? One theory is that more variable input can highlight which aspects of a task are relevant and which are not (color is useful for distinguishing between lemons and limes, but not for distinguishing between cars and trucks).

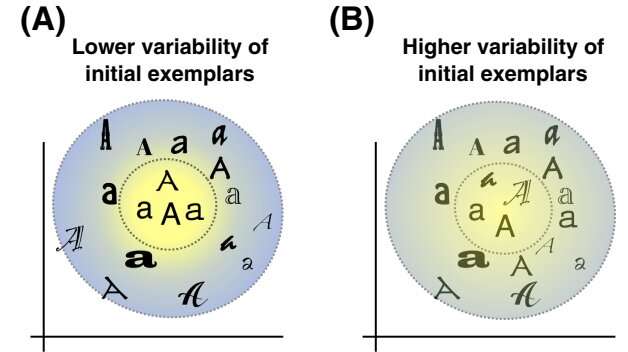

Another theory is that greater variability leads to broader generalizations. This is because variability will represent the real world better, including atypical examples (such as Chihuahuas).

A third reason has to do with the way memory works: when training is variable, learners are forced to actively reconstruct their memories.

Face recognition

“Understanding the impact of variability is important for literally every aspect of our daily life. Beyond affecting the way we learn language, motor skills, and categories, it even has an impact on our social lives,” explains Raviv. “For example, face recognition is affected by whether people grew up in a small community (fewer than 1,000 people) or in larger community (more than 30,000 people). Exposure to fewer faces during childhood is associated with diminished face memory.”

“We hope this work will spark people’s curiosity and generate more work on the topic,” concludes Raviv. “Our paper raises a lot of open questions. For example: Is the relationship between variability and learning broadly similar across species, or are there species-specific adaptations? Can we find similar effects of variability beyond the brain, for instance in the immune system?”

Community size matters when people create a new language

Limor Raviv et al, How variability shapes learning and generalization, Trends in Cognitive Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.tics.2022.03.007

Max Planck Society

Citation:

How variability shapes learning and generalization (2022, May 13)

retrieved 13 May 2022

from https://phys.org/news/2022-05-variability.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.